Recently, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court consisting of Justices Surya Kant and K V Viswanathan referred a suit filed by the state of Kerala against the Union of India to a Constitution bench for an authoritative pronouncement on the issue. It is an unprecedented litigation of great legal and constitutional importance.

The genesis of the case is also curious. The suit challenges an amendment made to the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, 2003. This is a parliamentary legislation. The amendment was made in 2018. As per the amendment, the Union of India gets the power to ensure the aggregate debt of the Union and state governments does not exceed 60 percent of the gross domestic product. That is to say, the Union government must fix the borrowing limit of the states as well, invoking the parliamentary enactment. The government at the Centre also issued letters to Kerala imposing a ‘net borrowing ceiling’ on the state.

Separation of powers is not merely a political or administrative concept. It is also an economic idea, as designed by the Constitution. Fiscal federalism is a facet of India’s democracy. Article 292 of the Constitution talks of borrowing by the Government of India (GoI) while Article 293 talks of borrowing by the states. In Article 293, there is a provision for making loans to any state by the Centre. It bars the state from raising a loan without the consent of the GoI, if any amount of loan the Centre gave the state is still outstanding.

Two things follow from this scheme of the Constitution: One, borrowings by the GoI and states are governed by two distinct provisions. This aspect is further fortified by the fact that public debt by the Union and the states are listed separately under the 7th schedule of the Constitution. Two, the requirement for the Union’s consent for borrowing by the state is limited to borrowing from the Centre only when the state has outstanding dues to the Centre.

Thus, there is constitutionally guaranteed financial autonomy for states. Financial discipline and stability are requirements for the Union as well as states. The Union, with this object, promulgated the FRBM Act. Several states also promulgated similar enactments. Kerala in 2003 enacted its Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act. This scenario is perfectly in tune with the constitutional scheme that rejects invasions and interferences.

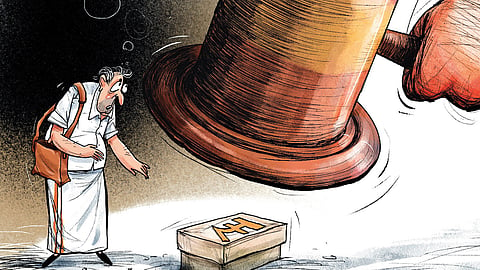

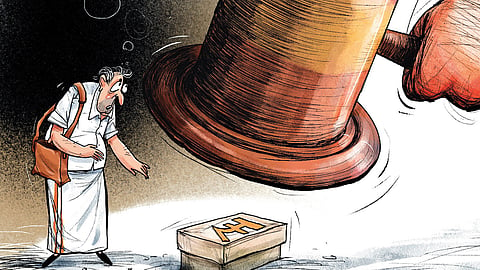

But the 2018 amendment to the central Act tried for the Centre’s intrusion on the states’ borrowing power. Thus by way of statutory amendment, the Centre paved the way to regulate the borrowing of states. This has an aggrandising effect. Since fiscal federalism is to be treated as part of the country’s Constitution, this amendment is clearly vulnerable to challenge.

The 2018 amendment was done without the concurrence of the concerned states. Evidently, the amendments to the FRBM Act were made by way of Finance Acts based on money bills. A money bill need not be passed by the Rajya Sabha. According to Article 109 of the Constitution, it is enough if the Lok Sabha passes it.

The so-called consultative role of the Rajya Sabha, which is supposed to represent the interest of the states, is minimal or ornamental in this regard. Thus, unilateral assertion of the Union that it can control the state’s borrowing has antagonised the states, especially those ruled by opposition parties. The Kerala government has argued that the amendment and actions based on it are vitiated by manifest arbitrariness.

There could be several instances where the states act in conflict with the Centre in financial matters. The limits to the borrowing capacity could be very well an area where the public at large may have concerns. Charges of financial profligacy are raised against the Union as well as the states. Therefore, in many of the conflicts, the GoI and some of the states are contesting parties. In such situations, the Centre cannot act as the judge of its own cause. Such disputes must be necessarily decided by an independent agency.

Though the Supreme Court has indicated the role of the Reserve Bank of India as the public debt manager of the states, the role of the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) in such situations requires to be emphasised. The office of the CAG, as a referee institution, could perhaps give a constitutional resolution for the problems arising out of the Centre-state conflict in the matter of borrowing and their limitations.

The CAG is established by Article 148 of the Constitution. Article 149 talks of its duties and powers. Those are “in relation to the accounts of the Union and of the states, and of any other authority or body” based on a parliamentary law. In the Kerala case, borrowing made by a state-owned authority called Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board, a statutory body established in 1999, engages in many financial dealings required for the developmental projects of the state. The CAG can, if necessary, investigate such dealings as well, based on a parliamentary law.

But instead of invoking the constitutional provisions in the right way, the Union has resorted to an amendment, which on the face of it does violence to fiscal federalism and the separation of powers as envisaged by the Constitution. Its aggressive assertions do not augur well to safeguard the people’s interest. Restrictions on borrowing that result in postponement of beneficiary schemes including pensions and assistance to the disadvantaged tell a sad commentary on the whole episode.

Extra budgetary borrowing is an integral and indispensable part of financial administration. An unconstitutional intrusion into such transactions can create enormous hurdles in the process of governance. Again, expanding the notion of the Union’s consent for states’ borrowing from third parties, too, goes against the scheme of the Constitution. As we have seen, Article 293 talks of the requirement for consent only as against the borrowing of the states from the Centre and not from others. It is meant to safeguard the interest of the Union as the creditor.

The decision of the Constitution bench is therefore vital in the realm of financial administration. In the ongoing elections, already there are federalist concerns raised from different corners. There is also a need for a national debate on the issue of fiscal decentralisation. Though the Constitution bench of the top court will decide the issues, it is also important to have a political discourse on the subject. At the end of the day, it is a matter not merely for the Union or the states, but for the people at large to brood over.

(Views are personal)

Kaleeswaram Raj | Lawyer, Supreme Court of India