Judges of subordinate courts are the backbone of the judicial system. The basic structure of our judicial system has evolved over the years. It was actually put in place when the British ruled India. The Simon Commission in 1930 emphasised the importance of an independent, competent and fair-minded judiciary that would enjoy the confidence of the people.

In 1933-34, a Joint Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms prepared the ground for the Government of India Act, 1935. It opined that while the Crown appoints the federal and high court judges, their independence was secured (a statement I doubt). But the appointments of judges of subordinate courts must necessarily be made by authorities in India who will exercise a certain measure of control over them in matters of their appointment, promotion and posting.

The Committee went on to comment that a system where the promotion of judges is in the hands of a minister exposes itself to the pressure of the government and is more likely to sap the independence of a magistrate. They also commented that judges of the subordinate courts are more closely in contact with the people and therefore their independence should be placed beyond question.

This sentiment, expressed way back in 1933-34, rings true even today, except the masters have changed. Instead of appointments being made by the government in power, today the control of the subordinate courts is vested in the high court of the respective state.

Under the 1935 Act, the appointment of judges in subordinate courts was to be made by the governors of provinces in consultation with the high courts. Consequently, in matters of appointment and transfer of judges of district courts, the reins of power continued in the hands of the governor. It was ultimately in 1948 in the conference of judges of the federal courts and chief justices of high courts that it was recommended that provisions be made to place this power exclusively in the hands of high courts.

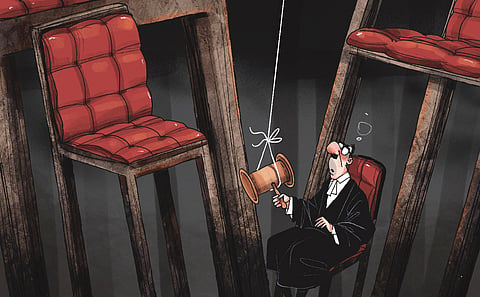

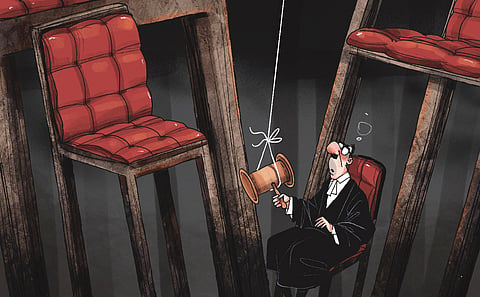

Under Article 235 of the Constitution, each high court has its own rules for recruitment, conditions of service, promotion and transfer of judges of subordinate courts. Yet, the perception amongst lay people is that subordinate judges are loath to exercise their judicial powers lest it stymie their chances of promotion. Each district judge hopes ultimately to be elevated as a judge of the high court.

Notably, 65 percent of the jJudges of the high court are appointed from a cadre of district judges by promotion on seniority, 10 percent on merit through the departmental tests, and the balance 25 percent from amongst legal practitioners. As of June 2023, the sanctioned strength of the district courts in India was 25,523.

Administrative control by high courts over the members of the subordinate judiciary impacts their independence in practice, particularly in the lowest rung of the hierarchy. This is natural as every judge would like to be elevated to the high court. Therefore, they look towards judges of high courts for their promotion, which also impacts the independence of the system at that level.

Appointments to special courts constituted under special statutes like the PMLA and the UAPA are important assignments and judges are hand-picked to deal with matters that provide fodder for news splashes. This provides judges with exposure to cases of high public importance. In such matters, special judges are seen unwilling to grant bail. We have seen, on occasions, that judges at that level who have rendered judgements against prosecution agencies in high-profile cases are transferred out. Even distinguished judges of the high courts have been transferred overnight.

We have also witnessed students, those opposing government diktats and participating in public protests, being denied bail for years. Even high court judges are unwilling to grant bail partly because of the stringent bail provisions under special statutes and largely due to the inbuilt hesitation about their promotional prospects being jeopardised. Sad, but true.

In the procedure for appointments to the higher judiciary, the chief justice interacts with the government. They say that law and justice should be distant neighbours and sometimes strangely hostile. A cosy relationship between the collegium, through the chief justice, and the executive allows for a process of give and take, which can negatively impact an institutional framework that should not allow judges committed to a particular ideology to be inducted to the higher judiciary.

Some appointments, in the recent past, have allowed for such judges to be appointed. One such judge, after quitting office and joining a political party, openly confessed to his affiliation to the ideology of a particular party. In many cases, such affiliations are publicly known but not commented upon for reasons easy to understand. This trend does not augur well. There can and should not be any compromise when it comes to appointments to the higher judiciary.

What we need is a complete overhaul of the system. No judge can be expected to function truly independently if his judgements are guided by factors relating to his promotion. The rationale behind the power of appointment, promotion and transfer of judges of subordinate courts being taken away from governments and vested in the high courts is still relevant. All that has changed is the exercise of control has been shifted from the executive to the judiciary.

This is also true of the appointments to the higher judiciary. The Supreme Court took away the power of the government to appoint judges to the higher judiciary and vested it in the collegium system. But the concern still remains the same. All that has happened is the institution now is required to be saved from the influence of the collegium.

We need to find solutions to make sure our judicial system is independent of external influences, both subtle and not-so-subtle. At the heart of the judicial system is the ability of a judge to render an opinion without fear or favour. But what is of utmost importance is that people in this country have confidence in our judges and our judicial system. Any erosion of that confidence presents a danger to the very foundations of our democracy.

(Views are personal)

(Tweets @KapilSibal)

Kapil Sibal | Senior lawyer and member of Rajya Sabha