The Securities and Exchange Board of India is one of the most important financial institutions in the country. Nearly 100 million Indians and thousands of foreign funds have invested their monies in India’s financial markets based on their trust in the credibility of the market regulator.

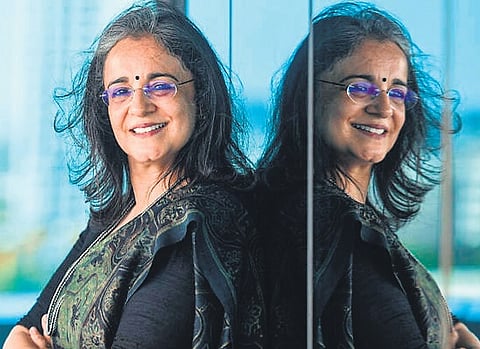

Sebi Chairperson Madhabi Puri Buch is the first person from the private sector to be appointed its head. She is now embroiled in a controversy over her and her family’s financial transactions. The Congress has brought out charges against Buch that they see as cases of financial impropriety. Buch, while not denying the transactions, has claimed innocence.

Both seem perplexed over why the other seems to be missing the obvious. This chasm is because of the figurative ‘suit-versus-safari’ (or sari) clash of expectations. Buch’s transition from a corporate executive (suit) to a public servant (sari/safari) has been trapped in the meritocracy dogma.

American research firm Hindenburg kicked off this controversy by highlighting Buch and her husband’s investments in offshore funds that were linked to the Adani group. Then the Congress came up with a slew of charges against Buch—including earning income through ICICI stock while being a regulator, her private firm earning income from corporates she was regulating, her husband earning crores through consulting assignments with corporates that were under Sebi’s ambit, and her continuing investments in stocks and funds.

The details were presented with evidence and an insinuation of conflict of interest and corruption. Buch responded that most of these investments were made before she became Sebi chair and her husband was entitled to earn by offering his expertise to corporates. She claimed there was no overt quid pro quo between her responsibilities as the Sebi chief and the income she or her husband earned—hence, she was innocent. Buch’s defence is a clear sign of a cognitive dissonance between her suit and sari avatars.

It’s said that when former Sebi chief M Damodaran was appointed to head the Unit Trust of India, he sold the meagre 50 SBI shares he owned to be completely free of any conflict of interest. I recall when the then Infosys CEO Nandan Nilekani took up the Aadhaar assignment with the UPA government in 2009, he went to great lengths to not only be conflict-free about his stock ownership, but also to be perceived as such. There have been several other professionals from the private sector who have held public office—including as Reserve Bank governors and chief economic advisors—in a fully conflict-free manner.

Buch sought public office for impact, power and authority after satiating her financial needs through the private sector. But she either does not want to or chooses not to recognise the demands of greater transparency and integrity of public office.

Standing to gain through stocks or funds even remotely linked to Adani—which Sebi was supposed to be investigating—while also being its regulator would be deemed a conflict of interest in any country, regardless of when the investments were made or if there was an explicit quid pro quo. It’s puzzling that this simple fact eludes Buch and her ilk.

The same set of people that defend Buch also, rightfully, scream conflict when people move from public office to private-sector positions after retirement. Former Finance Minister Arun Jaitley cautioned against judges’ conflicts of interest by saying, “The lure of a post-retirement job may corrupt their pre-retirement verdicts.”

If even an unknown future event can be construed a conflict, why should Buch’s known past investments in entities she regulates not be? Buch’s defence that there is no straight-line connection between her duties as Sebi chief and the income she and her husband earn is tone deaf, and misses the point that she has to be seen and believed as trustworthy by millions of stock investors.

Buch and her husband seem bewildered and enraged that their freedom to earn can even be questioned. Their response implies that as alumni of IIM Ahmedabad with decades of leadership experience in blue-chip companies, they have every right to legally earn however and whenever they want. Bolstering this argument, their IIM classmates issued a letter in support, alluding that the government should be grateful to have an extraordinary talent like Buch willing to move from the private to the public sector. Some other private sector executives have sermonised how it is against the nation’s interests to cast aspersions on Buch because this will prevent other private sector professionals or alumni of elite colleges from offering their services to the nation.

Buch and her sect epitomise what Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel calls the ‘tyranny of merit’. Meritocratic societies foster a deep sense of entitlement in successful individuals because they are led to believe they earned their success entirely by individual merit. Sandel posits that because they have emerged at the top through a ‘meritocratic filter’ of competitive examinations and organisational battles, there is a feeling of privilege and of deserving their rewards. By corollary, those who are not successful through this system are deemed deserving of failure.

In this hierarchy, the implicit premise is that the private sector is superior to public office, and hence ethical standards are different for people transitioning public-to-private versus the other way. Buch and her friends are blinded by the meritocratic halo and are unable to come to terms with the expectations of public office.

As one who transitioned from an Ivy-League-educated corporate honcho to a politician, I went through a similar confusion in reconciling with the demands of public life. I acutely understand how humbling and complex it can be for Buch to be caught in a meritocracy trap and suddenly be made to feel she is no longer special. The figurative solution to the suit-to-sari (or safari) transition is to have a uniform dress code for all.

Praveen Chakravarty

Chairman, All India Professionals’ Congress

(Views are personal)