Over the past month, the delimitation debate has taken wings. Ground zero of the debate has been Chennai, and its chief promoter has been the Dravidian government led by M K Stalin. They have endeavoured to create a common cause on this issue among the southern states, while they are warring petitioners and fierce competitors on other issues.

What preceded the delimitation debate in Tamil Nadu was the language debate in the context of the NEP or the National Education Policy. But that did not seem to catch fire like it used to once upon a time. The reason being that the idea of an exclusive linguistic state in present-day India may have begun to look anachronistic. A variety of cultural, sociological, demographic, technological and economic reasons may have caused this. But the truth, which pride may blindly dismiss, is the identities of linguistic states have transformed in recent decades.

There was a significant fact that stood out during the NEP debate in parliament. It was revealed that 67 percent of students in Tamil Nadu were enrolled in English-medium schools, while Tamil-medium enrolment had dropped from 54 percent in 2018-19 to 36 percent in 2023-24. In government schools, English-medium enrolment has increased five-fold from 3.4 lakh to 17.7 lakh in the last five years, while Tamil-medium enrolment in government-aided schools fell by 7.3 lakh. The statistics are likely to be similar, or even more depressing, for other south Indian languages.

This puts in harsh perspective the realities that ensnare a linguistic state. However, it does not suggest that Tamil Nadu or any southern state is fully or partially ready for Hindi to take over. It is just a powerful indicator that there is a steady, pragmatic movement towards a language that offers greater economic opportunities. It should be said that in the 75 years since becoming a republic, English has developed a presence especially in the south Indian mind, which is independent of its colonial legacy.

Tamil Nadu’s language arguments are often idiosyncratic. Even the Dravidianism spoken about is exclusionary in nature. It is an idea that does not travel beyond the linguistic borders. Therefore, their effort to present the south as one progressive block of late is not just a fallacy, but may soon allow their neighbours to read hegemonic interests in the region.

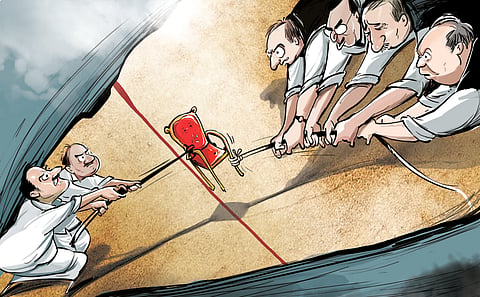

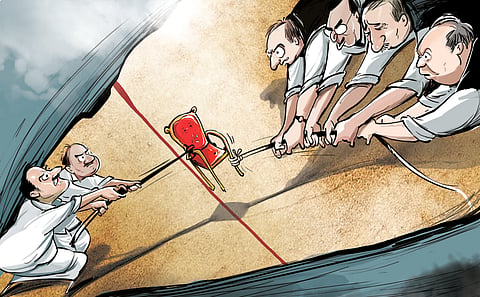

With this as the backdrop, it is possible to make linkages between the realities of the linguistic state and the delimitation debate in the hope of finding a reasonable solution. The seditious scare created about an unfair delimitation process is that the southern states may eventually break away. According to one projection, if delimitation goes through as it is being imagined today, demographic realities may ensure that the five southern states together may lose 26 seats if the Lok Sabha seats are frozen at the existing 543. If the Lok Sabha seats are increased to 848 as per the 2026 population figures, then the four north Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh may gain 150 seats, while the five southern states will add only 35 seats, with Kerala gaining none.

Since delimitation has to do with population figures and proportional parliamentary representation, the southern states have presented a victimhood argument that they are being punished for performing better on various development indices; for making a greater contribution to the nation’s GDP, and for making efforts to contain population growth. While this argument has enormous emotional traction, which should worry the Narendra Modi government, the total fertility rate (TFR, average births per woman in her lifetime), shows the northern states have performed better than the southern ones.

If the 1971 benchmark is looked at, the TFR levels for the southern states were lower compared to north Indian states, but the drop that north Indian states have achieved in over 50 years since is much higher compared to the south Indian ones. Therefore, this charge that the south has handled its population goals better than the north does not stand.

With all these facts and realities flying in the face of popular beliefs, how then should the delimitation process be managed? It is clearly not enough for the Modi government to assure the south will not suffer. It is not sufficient to say the seats for all states will be increased pro rata. It may have to work on lateral ideas.

Given the size of some large states like Uttar Pradesh, and also the crisis of linguistic states, which from time to time have showcased deep cultural incongruities inside their seemingly flat, homogenous identities imagined six decades ago, one wonders if the government should consider a second states reorganisation commission (SRC) as a starting point.

If the SRC imagines, say, 50 Indian states by 2040, on distinct cultural alignments within existing linguistic states, and/or conceives smaller states around big and potential cities as economic engines, then, there is a possibility that increasing parliamentary seats to give greater democratic voice would become relatively easier. There would be less fear of one or two big states dominating the political future of a diverse nation.

There is yet another way that delimitation could be conceived. Parliamentary seats need not be tied down to the existing model of individual states being given a specific quota. On the contrary, constituencies can overlap state boundaries to create a better scheme of proportional representation.

This will in no way affect the legislative powers of the states or harm federal interests because the 7th Schedule of the Constitution clearly identifies the state, central and concurrent lists. If people who belong to different states can contest Rajya Sabha seats in states they have nothing to culturally identify with, why should Lok Sabha seats not create a supra layer over strict territorial, linguistic, cultural or ethnic state boundaries? The phrases ‘national interest’ and ‘national unity’ may develop a new cosmopolitan resonance with this model. The European Union may offer some lessons to nuance this.

What the Modi government has done so far, largely, is to rework the past. If they invest time to explore these alternatives or provoke even better ones to emerge from the collective rumination of a nation, it may become the biggest item on its legacy list. It could change the map of India for the foreseeable future.

Sugata Srinivasaraju | Senior journalist and author of Furrows in a Field: The Unexplored Life of H D Deve Gowda

(Views are personal)

(sugata@sugataraju.in)