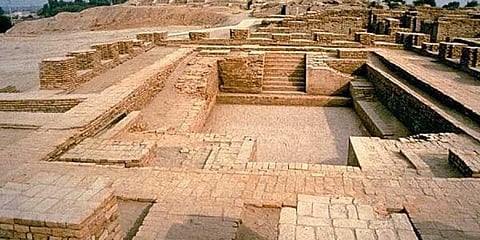

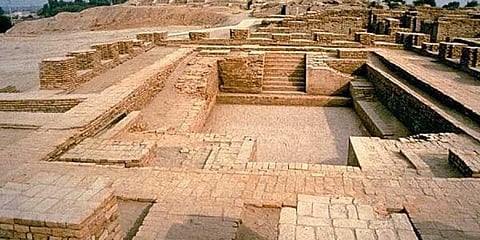

Among the several domed conical stones found along the Indus Valley, two objects stand out—a small tapered cone seated on a round base and a dome-shaped cylinder on a flat base with a protrusion on one side. From being a small aniconic object that transcended popular representations of the divine as a superman, the lingam’s depiction has grown—but not necessarily as a phallic object, as described by western Indologists. These depictions included simple cylindrical objects or pillars with carvings of Shiva’s face. It’s a Harappan legacy bequeathed to the Indian civilisation. The Rig Veda does not mention the lingam or even Shiva.

Lingam means sign or symbol—an abstract representation of Shiva. It’s fitted into the disc-shaped base called yoni, which means the source or womb. Together, the lingam and yoni represent the eternal process of creation and resurgence.

The Shwetashvatara Upanishad calls the lingam a symbol that establishes the existence of Brahman, one beyond any characteristics. The Linga Purana adds, “Shiva is without a symbol, without colour, taste or smell, beyond word or touch, without quality—motionless and changeless.”

As for the legend of their providence, there are four kinds: swayambhu (self-manifested), deivika (created by gods), arsha (created by rishis) and manusha (man-made). Among the swayambhu lingams are the frozen ice lingam at Amarnath and the naturally-formed rock lingam at Kedarnath. Even some even triangular mountaintops are called Shivalingam.

They are also classified by the material used or carvings. A mukhalingam generally has one, four or five faces, at times eight or more too. It’s sometimes carved with images of Shiva or of other deities. From the second century ACE onwards, several lingams have been found in Mathura, with Shiva in the front or as one to the four faces around the pillar.

In Cambodia, there is a chaturmukha lingam with Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva and Buddha carved on the four sides. A famous panchamukha lingam in the Pashupatinath temple in Nepal is six feet high and is five-faced: four facing the four cardinal directions and the fifth looking upwards. In the Buddhist Vajrayana Swayambhunath temple not far from Pashupatinath, several four-faced lingams are carved with Buddhist deities on each side. So the multi-faced lingam does not represent a phallus.

The panchabhuta lingams represent the five elements of earth, water, air, fire (energy) and space. Sita is said to have made the sand lingam in Rameshwaram that’s still worshipped. There are several temples where Shiva appeared as a column of fire or jyotirlingam. Out of the original 64, 12 remain around India.

The earth lingam of Ekambareshwarar temple in Kanchipuram is also made of sand and is bathed in oil, as water could dissolve it. The water lingam of Thiruvanaikaval in Tiruchirappalli sits on a perennial stream. The Arunachaleshwara of Thiruvannamalai sits on igneous rock, representing fire. The air lingam of Sri Kalahasti represents the wind: the flames inside flicker even when the airless garbhagriha is locked. Finally, the akasha lingam of Chidambaram is represented by empty space, his formless representation. None of these are phallic.

The earliest phallic lingam comes from the Parashurameshvara temple at Gudimallam in Andhra Pradesh. Shiva stands before it, holding a goat in his right hand and a water pot and battle-axe in his left, on the shoulders of a gana. This lingam was probably originally situated beneath a tree. It has been dated to the 2nd century BCE, but its high degree of polish is typical of Mauryan art. The Gudimallam Shiva is probably the only surviving south Indian icon of the Mauryan period. He is a hunter, a popular form of the deity.

Hunter Kannappa Nayanar plucked out his eyes to offer them to the lingam at Sri Kalahasti, 40 km from Gudimallam, while Shiva is Kirita the hunter on the monolithic carvings at Mamallapuram, 160 km away. Lingodbhavba, or Shiva emanating from the lingam, was probably inspired by the Gudimallam Shiva.

The Cholas were staunch Shaivas who built massive lingams in temples, although the smaller, original ones are also preserved and worshipped in several places. Neither of them is phallic. When a Chola king or queen died, the body was cremated and the ashes buried beneath a lingam. The temples around them were called pallipadaikovil. Many such temples were built in the 10th-12th centuries CE.

A chala or moveable lingam is worn as a pendent on a necklace by the Veerashaiva Lingayats, a tradition from Karnataka. Lingayat men and women wear an ishtalingam inside a box strung on a necklace. It is about divinity living and moving with the Lingayat devotee.

The signifier from Harappa was not phallic. And over the following millenniums, its depictions have taken various forms. Our culture is richer for this variety today.

Nanditha Krishna

Historian, environmentalist and writer based in Chennai