I received a beautiful New Year message from a Sikh friend: “End 2024 with shukrana (thanksgiving), start 2025 with ardas (petition for well-being).” This naturally brought to mind that January 6 is the 358th birth anniversary of Guru Gobind Singh. Date-wise, after Rana Pratap and Shivaji Maharaj, Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh Guru, is India’s last great classical hero, and Hindus revere him as devotedly as Sikhs do.

Among his many brave deeds, he founded the Khalsa, the Sikh army created to fight injustice and oppression. I can never forget the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Khalsa in 1999. Delhi was a festive sight, with thousands of cars flying saffron pennants with ‘Ik Onkar’ (God is One) in Gurmukhi script. To offer respect, I went to Delhi’s seven historic Sikh shrines and was deeply moved by the sincerity of devotion there, the soothing sound of the shabad kirtan, the cleanliness, and the characteristic generosity with which the gurdwaras fed everyone langar, the free community meal.

Growing up in Delhi, I had the subconscious assurance that, should the need arise, I would never go hungry in my hometown. All I had to do was show up at one of the great gurdwaras, and I would be fed. This assurance gives a certain confidence to those who know it—I have never seen a Sikh beggar.

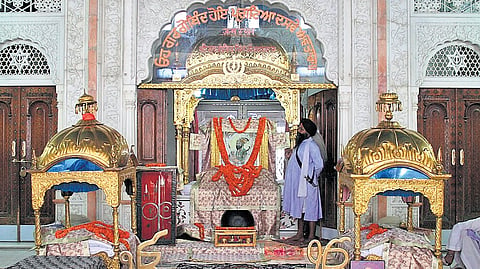

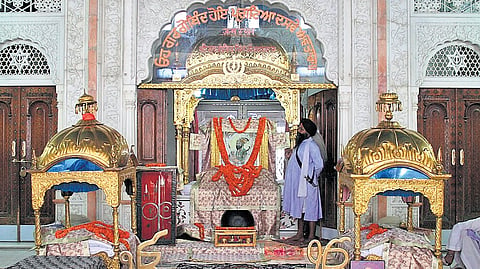

Of these historic Delhi gurdwaras, the one that hit me hardest in the gut was Gurdwara Shishganj in Chandni Chowk. It was built on the site of Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom. He was the ninth Sikh Guru, the father of Guru Gobind Singh, and was petitioned by a group of Kashmiri Hindus to save them from the religious persecution of the Mughals.

Guru Tegh Bahadur attempted to find a peaceful solution with Aurangzeb. But he was arrested and publicly beheaded in Delhi on November 11, 1675, by Aurangzeb’s order, both for refusing to convert to Islam and to try and suppress the conflict with the Sikhs.

Guru Tegh Bahadur thus sacrificed his life to protect the religious freedom of the people. He is venerated as ‘Chadar-e-Hind’, the protective cover of India. His verses, the Vairagmayi Bani, are profoundly stoic.

Another historic gurdwara is at Majnu ka Tila in North Delhi. I have read that it was originally built in 1783 by the Sikh military leader Baghel Singh Dhaliwal to commemorate the stay of no less than Guru Nanak Dev himself. Baghel Singh and his 40,000 troops entered the Red Fort in March 1783 and occupied the diwan-e-am or darbar hall. The Mughal ‘emperor’ Shah Alam II made a deal with Baghel Singh, allowing him to raise gurdwaras on Sikh historical sites in the city and receive six annas in a rupee of all the octroi duties in Delhi.

The general camped in Subzi Mandi (still thriving in Old Delhi) and identified seven sites connected to Sikh Gurus. He had shrines raised on them within eight months. Meanwhile, a saying grew popular in Delhi that people still use as an analogy for diminished power—‘Az Dilli ta Palam hukumat Shah Alam’, meaning ‘Shah Alam’s rule is from Delhi to Palam’, a village then on the outskirts that later became the site of Delhi airport, a distance of about 23 km today.

As for Majnu ka Tila, it translates to ‘hillock of Majnu’. It is the mound by the Yamuna where an Iranian-origin Sufi mystic, Abdullah, also called Majnu (meaning ‘lost in God-love’), met Guru Nanak Dev on July 20, 1505. Scrawny from fasting, Majnu ferried people across the Yamuna for free in the name of God. Majnu was spiritually transformed by his meeting with Guru Nanak and became his ardent follower. Guru Nanak was so pleased with Majnu’s spirit of public service and desire for enlightenment that he declared the place would be called ‘Majnu ka Tila’ forevermore. And it is, to this day.

Born into this spiritual tradition, Guru Gobind Singh was made the tenth Sikh Guru at the age of nine, after his father Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom by Aurangzeb’s command. He grew up into a warrior, scholar, and sublime poet. He had to endure the tragic loss of his four sons.

Two were killed in battle and the two younger boys, under six and just eight, staunchly refused to convert to Islam when captured by the Mughals. These brave sons of a courageous father were then walled up alive by Wazir Khan, the Mughal governor, to the people’s great anguish. The Guru blessed Sher Mohammed Khan, the Nawab of Malerkotla, who opposed this barbarity to little children.

Guru Gobind Singh was fluent in Sanskrit and Persian. He sent a stinging letter in Persian to Aurangzeb in 1705 called the Zafar Nama (Epistle of Victory), with these famous words, ‘Chu kaar az hamha heeltedar gujast, Haal astburdan bashamsheerdast’, meaning ‘When all attempts at peace have failed, it is fitting to pick up the sword’. This rebuke demoralised the ageing tyrant, who had no answer to this truth about himself.

Guru Gobind Singh’s composition, the Dasham Granth, contains the Chandi Charitr Ukati Bilas in praise of the Devi. Classical dancers emote today to exquisite verses on Radha from the Dasham Granth. The Guru’s words from the Chandi Charitr, ‘Nishchay karapni jeet karoon’, meaning ‘With determination, I will triumph’, is the motto of the Sikh Regiment in the Indian Army.

Guru Gobind Singh’s jayanti is truly of great moral inspiration and significance in Indian history, that such a one was born to this land.

(Views are personal)

(shebaba09@gmail.com)

Renuka Narayanan