In April 1969, students at Harvard University protested the American war on Vietnam. It was a gesture of defiance against the regime that went beyond the campus. The next president of the university, Derek Bok, who assumed office in 1971, talked about the social commitment of modern universities in his seminal work, Beyond the Ivory Tower. It highlighted the importance of academic independence and political neutrality in universities.

Universities are, ultimately, centres of truth and knowledge. They are also important markers of resistance against the arbitrary use of power. In the field of science, too, universities are to serve humanity beyond territorial limits. Hence, academic freedom at universities has a direct link to a country’s democracy. The cerebral ecosystem of a nation is often created and maintained by the free exchange of ideas in the higher education system.

Universities teach us to question, criticise and analyse the system we live in. They motivate us to dream of a better tomorrow for ourselves and our world. In an essay, scholars Emily Chamlee-Wright and Bradley Jackson said, “If universities are to have a future as cornerstone institutions of a free society, they must assert their role as caretakers of the liberal project.”

In India, a recent draft notification by the University Grants Commission has ignited criticism from various corners on several aspects. Some feel the proposed regulations allow for enhanced academic flexibility, which is a welcome step. According to the draft, one can teach based on her highest level of qualification, even if her earlier level of learning was in a different topic. Others feel this would dilute the rigour of the subject requirement, which in turn will impact faculty quality. There are controversies on whether the revised parameters for evaluation of merit of aspiring teachers would be a healthy departure from the present numerical score-based system that focuses on the Academic Performance Index.

Another facet of the new draft is an effort to make the recruitment process more inclusive by taking in people from various categories including the differently-abled and sportspersons.

One contested part of the draft is Clause 10, which permits induction of eminent and experienced people from “industry, public administration, public policy and/ or public sector undertakings, with a proven track record of significant academic or scholarly contributions” as vice-chancellors of universities. Thus, apart from distinguished academics, an industrialist would also be eligible to be appointed VC of an Indian university. This expansion of the zone of consideration is problematic as it could accelerate the process of corporatisation of the centres of excellence. Commercial interest, like political interference, can severely damage the autonomy of universities.

The hyper-commercialisation of universities in India, except the traditional open universities, is a serious and complicated issue. As of now, education in some prestigious private universities has become the privilege of the elites. The proposed regulation could be a first step to extend the corporate culture to public universities as well.

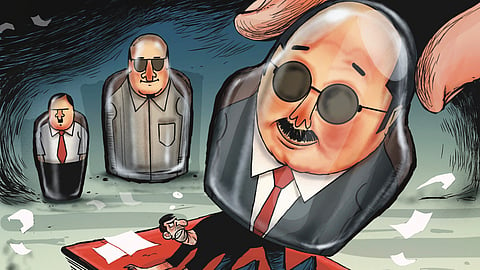

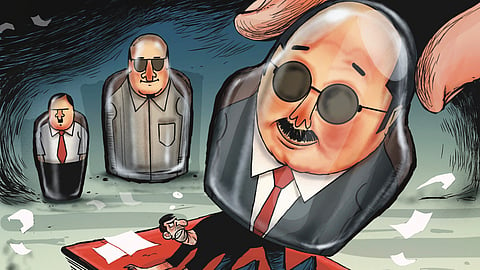

The draft rules provide unbridled power to state governors in constituting the search-and-selection committees to choose VCs. The governor, as chancellor, can appoint someone from the list provided by the committee. The composition of the three-member committee tasked with the selection is essentially centralist. A nominee of the chancellor, often the state governor, a UGC nominee, and a nominee of the university’s governing body would constitute the committee.

This would mean representatives of the Centre would constitute two-thirds of the committee. Not only that the state government remains unrepresented, but the university representative can also be sidelined in the process of selection. Her dissent cannot sway the choice of VC.

It’s not as if higher education in India is otherwise free from political interference. Former UGC chairman Ved Prakash quoted the National Knowledge Commission to say that “interventions from government and intrusions from political process” have substantially impacted the autonomy of universities.

The current move reflects something more than mere politicisation. It arms the mighty Centre to meddle with the affairs of universities, ranging from the preparation of curriculum to appointing teachers. By fencing out state governments from choosing VCs even in the state universities, the draft regulations take an anti-federal posture. That will shrink the open spaces, which in turn will diminish academic independence.

The federal traits in the realm of higher education deserve to be preserved. The multiplicity of external controls over universities has already accelerated the centralisation of India’s higher education system. Because education falls under the concurrent list of the Constitution’s 7th Schedule, the Centre has legislative competence. This led to the passage of laws that recognised institutions like the UGC, All India Council for Technical Education and National Board of Accreditation. Yet, the Centre’s use of such institutions to extensively influence the higher education system goes against the federal spirit of the Constitution.

Ironically, the UGC—which has issued the draft—was given statutory recognition through a 1956 enactment emulating the University Grants Committee of the UK. The UK abolished the committee in 1989, paving way to better decentralisation of British universities. In India, diversification and decentralisation of higher education suffered severe setbacks due to hyper-centralisation, which imposed stiffness and dependence in the academic world.

The present controversy should allow us to think beyond the Centre-state tussle for a final say in the choice of VCs. The glaring deficit of the draft is that it fails to radically alter the academic ecosystem in Indian universities by emancipating them from the clutches of corporates and governments.

Political and governmental control over universities is somewhat ensured legislatively in the country. Yet, an imaginative policy can still improve the level of autonomy and academic freedom in the centres of excellence. A revival of a fearless and liberal atmosphere in our higher education system can happen only with a great sense of academic statesmanship. The draft regulations are marked by its sheer absence.

(Views are personal)

Kaleeswaram Raj

Lawyer, Supreme Court of India

(kaleeswaramraj@gmail.com)