Political parties in India ostensibly have two kinds of rebels or dissenters. The first kind of rebels are the common, pedestrian variety. They crudely bargain for power. They could be seeking an election ticket, a higher position, a hefty ministerial berth or greater funds. They threaten to disrupt if their expectations are not met.

The second type is rare to come by. They are the ones who put their parties in a piquant moral situation. They prick the conscience of their parties. They do so by either arguing from a higher ideological plane; by prescribing higher values to their colleagues, or via aligning themselves, parallelly, with a purpose far greater than that being advocated by their parties at a given time.

These high-minded grumblers, if we may call them so, may be difficult to handle, but parties cannot easily dismiss them. That is because they form a virtuous smokescreen before the voting masses, and sometimes become fossiliszed symbols of the foundational principles of their parties.

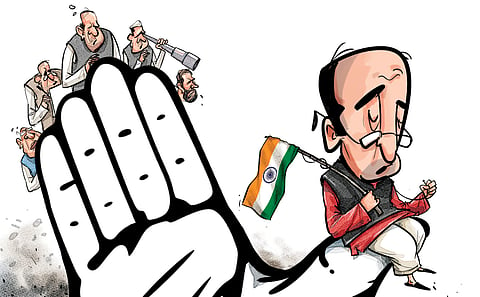

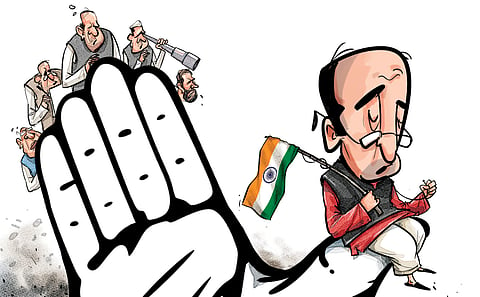

In recent days, Shashi Tharoor, a member of parliament from Thiruvananthapuram, has come across as the second type of rebel within the Congress. Ever since he became the most eloquent, nonpartisan voice by leading an official delegation to foreign nations to explain India’s war against terrorism, his party has suspected his loyalty. They have coldshouldered him, attempted to play down his importance and even underplayed his certain mastery over English.

But more the effort the Congress has put in, Tharoor has sparkled more in the eyes of a larger audience. The headlines have not stopped chasing him. To the extent that many think he is independent of the Congress; that he may get a newly-crafted diplomatic assignment under the Modi dispensation to regularize his patriotic services; that he may even cross over to the BJP and become a minister in the cabinet, or ultimately head to Kerala to head the state.

All these are far-fetched. Tharoor is not politically naïve to start believing the publicity that surrounds him. However, he is smart enough to leverage the fair winds among the masses in his favour, to position himself as a singularly independent politician in India in times of polarised affinities. It is this well-crafted independence that gives him the power over two large warring ideological constituencies.

Tharoor’s recent statement on the RSS was proof of his political deftness. It directly challenged the Congress position on the issue, and more so that of Rahul Gandhi. Tharoor said: “At the time of the adoption of the Constitution [75 years ago], Mr Golwalkar, among others, said that one of the great flaws of the Constitution is that there is nothing of the Manusmriti in it. But I think the RSS itself has moved on from those days. So, as a historical statement, it’s accurate. Whether it’s a reflection of how they feel today, the RSS should be in the best position to answer that.”

The RSS and the BJP were somewhat let off the Congress hook after this statement. They had been segued out of embarrassment, courtesy Tharoor. Since the debate was happening in the context of 50 years of the Emergency, when the Constitution was dismantled by Indira Gandhi, it was as if a mirror of duplicity had been held before the Congress. The party’s self-righteous propaganda on the Constitution had been happening without it actually apologising for the horrors it had perpetrated during the Emerg ency and the anti-democratic institutions, including the idea of political dynasties, that it had established.

The ruling Modi dispensation seems to have happily adopted Tharoor because it saw the need for a reasoned patriotic voice on the international stage after Operation Sindoor. Perhaps they realised that their own jingoistic tone wouldn’t work. And Tharoor needed an open arena to escape the stifling atmosphere inside his party. The regime’s need and the politics of Tharoor appears to have aligned at the same time to cause a massive heartburn within the Congress. Yet, they cannot be seen acting against him, at least not immediately.

It is apparent that the Congress is not enjoying this checkmate. The dynasty may eventually act and its courtiers may add to the glossary of trolls, yet it won’t be as easy as seeing off others who had crossed over for power. Over the years, Tharoor has become an aspirational symbol of new India where everybody seems to want his charm, his coiffure and his English accent.

In contemporary history, there are two outstanding examples that reconstruct a similar moral quandary that Tharoor has put his party in. V P Singh, in the mid-1980s, had similarly thrown a moral challenge at Rajiv Gandhi and the Congress. Even while inside the party and the cabinet, he had accused the regime of corruption and grabbed the mantle of ‘Mr Clean’.

Singh’s biographer Debashis Mukerji writes that on May 16, 1987, at a Congress rally in Delhi’s Boat Club grounds, Rajiv Gandhi could not contain his growing unease against Singh. Without naming him, Rajiv said: “Today we should remember how a Mir Jafar rose in our midst, a Jaichand rose in our midst, to weaken the country… we’ll give them a fitting reply.” Jaichand was purportedly Singh’s ancestor and the implication was clear. Singh left the rally midway and the rest was history.

Another example is of Somnath Chatterjee, who was expelled by his party for not stepping down as speaker of the Lok Sabha during the no-confidence vote in July 2008 over the India-US nuclear deal. Chatterjee had been a 10-time MP from the CPI(M) and took a perfectly constitutional and ethical position against his party’s dogmatic politburo line, which had in 1996 denied Jyoti Basu the prime minister’s chair.

In his autobiography, Chatterjee said: “My resignation as speaker, [Jyoti Basu] felt, as I too believed… that I was compromising my position as the speaker and allowing my actions to be dictated by my political party, which would be wholly unethical and contrary to the basic tenets of parliamentary democracy.” After 2008, the CPI(M) was wiped out on India’s electoral landscape.

After recounting these events which modestly changed the course of history, it will be interesting to watch how the patriotic interests of Tharoor will play out against his party’s addled interests.

Sugata Srinivasaraju | Senior journalist and author of The Conscience Network: A Chronicle of Resistance to a Dictatorship

(Views are personal)

(sugatasriraju@gmail.com)