The Gutenberg revolution appears to be waning as the written word, the defining mark of civilisation—whether on Babylonian stelae or in racy detective novels—recedes in the face of the ever-compelling power of images and voice. The written word is shaking off the grip of regimentation, which had tightened over the centuries since printing caught on in Europe and later, dictionaries formalised language.

Young people no longer read editorials to learn hieratic language. Instead, they are at ease with creoles, pidgins, slang and memes. But ironically, high feelings persist about language as a political and cultural marker of identity, purity and authenticity. Notable exception: at the press conference after signing the India-UK free trade agreement, a struggling Hindi translator was told to feel free to use English words.

Meanwhile, Maharashtra is upset about the three-language formula. Governor C P Radhakrishnan has weighed in on the problem of “linguistic hatred”, and recalled seeing a north Indian man in his home state of Tamil Nadu being beaten up for not knowing Tamil. Language politics in Tamil Nadu, an element of the Self-Respect Movement, was a bulwark against the Union government’s promotion of Hindi, which sought to flatten cultural diversity and make the states politically accessible to Delhi. Many states in the east, west and south didn’t enjoy being pushed around, and Tamil Nadu made it an enduring political issue. But it is rare for someone from the state to admit that linguistic assertion has an unpleasant side. An extreme example: the Second World War was triggered by Hitler’s determination to connect German-speaking populations in East Prussia and Austria with the German nation—“Ein volk, ein Reich, ein sprache”, to rip off a Nazi slogan concerning the Führer.

That was over 80 years ago. In the mean time, the world has globalised at a speed not seen since classical times. This could have been an era of bridge languages like Urdu. Instead, machines, the internet and their users are beating down the formalisms of language, and what was unthinkable is now doable.

When Kemal Ataturk switched Turkish from the Arabic-based Ottoman script to the Roman alphabet in 1928, it was a radical act. The measure, intended to bring Turkey closer to the West, was denounced by critics as a “cultural rupture”, as older texts became inaccessible to younger people. Perhaps it worked only because 6 percent of Muslims were literate at the time. But ever since Usenet launched group communications over the internet, before most languages had digital fonts, phonetic communications in the Roman alphabet have been commonplace.

And now, AI-powered translation is the norm. When Tony Blair’s Britain asserted multiculturalism in the late 1990s, the road sign of Bangladeshi-intense Brick Lane in London was rewritten in two languages, English and Bangla. When Monica Ali’s novel Brick Lane became a bestseller, it felt like borders were dissolving. Decades later, in the US, which has become multicultural without quite preparing for it, machine translation is creating weirdness. Public institutions like hospitals and transport have signs in multiple languages including Hindi and Bangla, but what they say sounds inhuman. Naturally, because this language is machine-made.

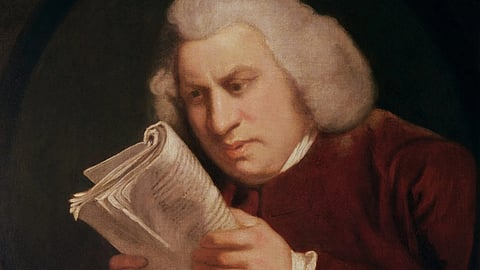

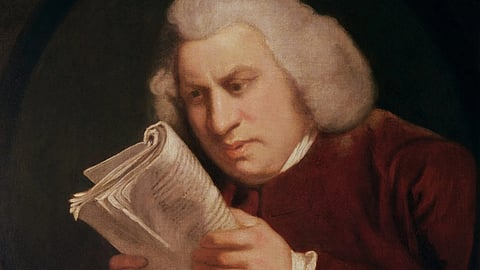

Across borders, there is concern that young people do not read these days; but let’s focus on what they do read. YouTube loyalists read closed captions generated by a machine. These are frequently incorrect, but it doesn’t bother anyone because the world’s language purists have either given up the ghost or the struggle. The dictionary is just another book and books are archival legacy media. If Samuel Johnson were around, the dictionarist who said that language is the dress of thought would have dismissed us as ragtags, with bobtails barely concealing our modesty in scanty hashtags.

Why is this happening? Information storage and retrieval began with visual and auditory media—cave paintings, dance performances, oral epics and songs. But why are they regaining salience? Because the written word was the most efficient storage medium for about five millenniums, from the clay tablet libraries of Babylon to Dewey Decimal via the Gutenberg press. But over the last three decades, magnetic and optical data storage has scaled up so rapidly that the contents of a refrigerator-sized magnetic tape bank of the 1970s now fit on a microSD card. With AI, it is normal for data processing to use as much power as small towns.

The written word is no longer essential for storage, and the human race is again embracing the audiovisual media with which it had begun to encode culture millenniums ago. Ironically, it’s a step back—there is now room enough for all the misbegotten utterances that the race can dream up.

In a strange case in bilingual Belgium, an attendant in a train running through Dutch-speaking territory greeted a passenger in French and faced proceedings right away. The proceedings have just ended, and the harassed attendant has turned language activist—he is selling coffee mugs bearing greetings in both languages to promote linguistic amity.

The resurgence of audiovisual media at the expense of text is starkly visible in politics. From West Bengal to Washington, visual media personalities are prominent in legislatures, and few of their most important associates can be accused of learning, or even literacy. Win some, lose some, say the Americans, who are postmodern—in the sense that they have never respected linguistic formalisms very much.

Pratik Kanjilal | SPEAKEASY | Senior Fellow, Henry J Leir Institute of Migration and Human Security, The Fletcher School, Tufts University

(Views are personal)

(Tweets @pratik_k)