Ever since President Donald Trump began unsettling the United States, commentaries in formal and informal exchanges have often sighed that the very idea of America has come under attack. The desperate sigh, that could cover miles and stretch across continents, makes a distinction to communicate the decline of the ‘free world’ and our times.

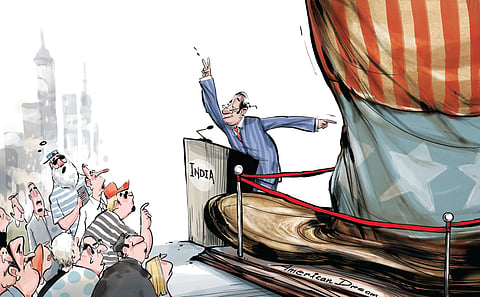

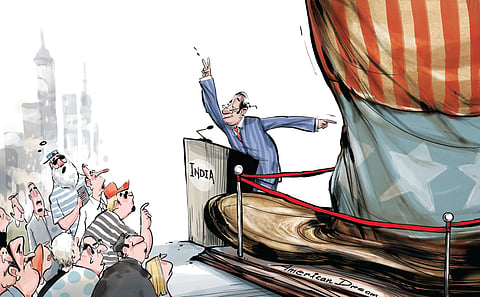

The standard progression of the narrative indicates it is one thing to target immigrants, foreign students, trade, environmental agreements, the military and monetary pacts. But to maul and dismantle the long-held perception of the US, which is willy-nilly linked to a certain rational construct, liberal ethos and cosmopolitan embrace, is a tectonic shift. If a nation ever had a fantastic marketing line in history, the US had it in the sublime phrase— ‘The American dream’. The suggestions emerging now are that the dream seems to be over; it has turned into a nightmare.

Although ‘American dream’ sounds almost like a truism, it has meant many things to many people both inside and outside the US. It’s like a phrase with a universal semantic connotation, but the dream itself has been nuanced across generations. America allowed immigrants to chase diverse freedoms, liberty, the good life and democracy; while encompassing a Protestant ethic, an emphasis on individuality and individual success, and a certain meritocracy. It has also accommodated an unabashed worship of profit. People have picked what they wanted, depending on where they stood on the arc of their personal progress.

The idea of the American dream was nearly always about the young and their flaming aspirations. It excluded the poor, the disabled, the sick and the elderly. The phrase perhaps also taught one to play down hardships, pain, loneliness and a variety of discriminations to be perennially on a junket of celebration. That is because to challenge the positivity of the phrase meant to negate the choices one had made to chase the dream. This is especially true for an immigrant.

An immigrant in America constantly markets success, opportunity and purposefulness, which is argued as missing in the nations of their origin. It is this marketing pitch and mythology that has enticed millions to somehow reach the borders of the country, spending enormous sums of money on touts while surviving ghastly routes. One wonders if such people would ever get a return on their investment. Therefore, they choose to play for the future, for an un-guaranteed and distant comfort of their future generations. Ironically, for such people to merely survive also means living the American dream.

Only prosperous countries can create a dream like the one America has manufactured. This dream consumes every other dream. A top psychiatrist once told me there was nothing called an Indian dream because all such dreams were fragments of the American dream. America’s biggest export has been its dream. No country in the world has put trade barriers and tariffs on it. It acquired a greater ring ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although China has emerged in the last couple of decades, it has never been able to export a dream. When Covid struck, and people disparagingly called it the ‘China virus’, it mortally struck at the possibility of such an export.

Even within the US, people have long felt that the American dream has been ‘stolen’ because wealth distribution in the past half-century has become skewed. A minuscule percentage of Wall Street, Ivy League and Silicon Valley types are accused of having rigged the system. They argue that between the 1950s and the 1970s, the American dream had created “shared prosperity” and expanded the middle class. In 2012, Pulitzer-winning journalist Hedrick Smith even wrote a bestseller titled Who stole the American dream? Philosophers like Michael Sandel at Harvard have also questioned the meritocratic system—an inevitable component of the dream.

Historians and commentators have seen the 1970s as a decade of transition in the US when parts of the powerful American establishment started rethinking its welfarist idealism of the 1950s through the 1960s. They were plotting to impart a harder pro-business, laissez faire identity to the nation. This put the ‘share-the-wealth ethic’ under a cloud and aided the burglary of the American dream, eventually. From being an ‘empire of production’, it started moving towards becoming an empress of consumption. The loss of jobs argument that began then haunts America to this day.

In India, of course, the 1970s was the reverse. The Nehruvian-socialist dream had taken a crude turn. We were into nationalisation of nearly everything. The state was the final arbiter of nearly everything from industrial licences to prescribing the size of the family that one should raise. The Emergency was a part of this authoritarian micro-management of a nation’s destiny. India’s middle-class expansion came late, only in the 1990s. That is when we borrowed the American dream that was already in a crisis.

Even during the 1950s and 1960s America, although one section imagined the full bloom of the American dream, racial inequalities and segregation ensured the dream was a truncated, one-dimensional affair that cleverly brushed everything that disturbed the formulation under the carpet.

Those who dreamt the American dream when the first waves of big immigration happened from India, notoriously labelled the ‘brain drain’, constructed the dream very differently. Economist J N Bhagwati even spoke of a ‘brain drain tax’. They did not abandon their motherland, but had a constructive narrative that was about scouting for technology, enterprise and education to take back. Interestingly, rural development was a running theme among the conscientious who had migrated in the 1960s and 1970s.

All this, of course, changed in the mid-1980s when a new generation of Indian-Americans, quite naturally, grew independent of their obligations back home. Assimilation in American society became a far greater pull. In the next few decades, India became an important member of the global technology network. For Indians, the American dream changed yet again. The diaspora perhaps imagined that the ‘brown’ had escaped the humiliations of the ‘black’ and had found a seat at the high table of American destiny. They had become an aspirational class of power and influence back in India, which had become a back office for the American dream.

Sugata Srinivasaraju | Senior journalist and author of The Conscience Network: A Chronicle of Resistance to a Dictatorship

(Views are personal)

(sugata@sugataraju.in)