What is the defining purpose of education? Is it to make more people literate, create economic resources for a country, skill its population, reduce unemployment, or more? Mahatma Gandhi once said, “Literacy in itself is no education…By education I mean an all-round drawing out of the best in the child and man-body, mind and spirit.” In that vein, education can be viewed as necessary to create thoughtful citizens with the skills to navigate an ever-changing world, who can engage and negotiate with the instruments of democratic rule and create a more inclusive, sustainable future.

Today, the world is made increasingly uncertain by conflicts, climate change, and the unfettered growth of artificial intelligence. In these circumstances, education systems need to produce aware, young people with the skills necessary to solve the problems they are likely to face. Mechanical knowledge of subjects is no longer prized; it is the ability to put that knowledge to use that is viewed as important. The twin responsibilities of education systems, therefore, are to prepare young people for life and its challenges, and to ensure each young person learns effectively by providing them the opportunity to do so at their own pace.

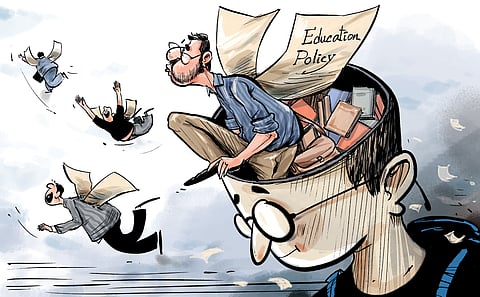

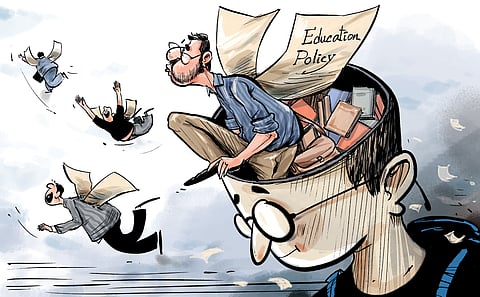

Given this, where do we stand today? From a policy perspective, setting aside for a moment the political discussions under way in different parts of the country, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 provides a reasonable framework for progress—one that would help achieve the very goals mentioned. However, policy documents are one thing and practical implementation quite another—and it is in the latter that progress has been uneven, or we have often been found wanting.

First, let’s look at the foundation. The latest Annual Status of Education Report notes an uptick in reading and mathematical abilities among schoolchildren after the government’s emphasis on early learning. However, that uptick starts from a low base; with only 25-45 percent of children across grades able to read or do simple maths, we are still far from where we need to be. The Unified District Information System for Education report for 2023-24 shows that only 54 percent of all schools have access to the internet while only 50 percent have functional computers for students.

Combining our relatively low levels of literacy and numeracy with incomplete access to technology creates an alarming picture that we need to address quickly. A world that values the ability to use and control technology, has little use for young people who can neither access the necessary information nor use the means to manipulate it.

Only 28 percent of eligible students are enrolled in higher education. While this marks a significant improvement over earlier years, it is too low a number when considering the universe of young people. We have the world’s second-largest higher education system, with some 58,000 institutions. But the truth is that the quality of these vary greatly, which is why only a few witness a life-or-death competition to enter.

A report by the Confederation of Indian Industry a few years ago showed nearly half the seats in engineering colleges for the mechanical stream had no takers each year. Unfortunately, the solution to low enrolment is not in simply opening more institutions, because as we have experienced, not enough qualified teachers are available to run them.

A useful indicator of the output of a higher education system can be the number of research degrees annually issued. Compared to China, the only other country with a population approximating ours, we produce 29,000 doctorates a year to their 56,000; but the quality of many remains questionable. While that still makes us the third-largest producer of doctorate degrees in the world in numerical terms, it leaves us well behind China and the US (71,000) in both quantity and quality.

In financial terms, India spends on average 4 percent of its GDP on education, which aligns with the expected global benchmark of 4-6 percent per year. Of this, roughly half goes towards school education and the rest to higher education. But in each case, a substantial portion goes towards staff salaries, leaving little for innovation and improvement. There is, therefore, a need for us to consider higher investment in this sector, both as a percentage of GDP and government expenditure, in order to support areas that get less attention such as curriculum restructuring, learning assessment, innovation in teaching, and improved coordination between the various stages of education. At both the school and higher education stages, the availability of private players has increased significantly in recent years. But this availability comes with an equity challenge, because the cost of education in these institutions is considerably higher than in government-run ones, thus leaving out those who do not have the means. Investing in improving state institutions, while also providing an increasing number of deserving students the means to access private education, could be one way to take a balanced approach. Education systems that have done well in international assessment studies—such as those in Estonia, Finland and South Korea—have demonstrated certain key characteristics that have enabled them to improve learning outcomes. These have included adequate investment, a strong and detailed curriculum, well-prepared teachers, strategic and regular use of robust assessments, and attention to the psycho-social-material needs of learners, coupled with a healthy social respect for education. The NEP does indeed address these and several other issues, and the challenge for us will lie in the extent to which we are able to successfully take a coordinated approach. Writing Deschooling Society in 1971, Ivan Illich said, “We have become unable to think of better education except in terms of more complex schools and of teachers trained for ever longer periods.” Instead, he suggested that we invert the education funnel that channels students into particular directions, imagining instead the creation of opportunities to establish a web of learning connections. What our education system needs to create are lifelong learners who can use those connections and acquire the skills needed to deal with the only certainty in today’s world—uncertainty.

(Views are personal)

Amrit Kaushik

MD and CEO, Australian Council for Educational Research, former lead consultant, Unicef, and former Director, Union education ministry