There are newspaper reports that the Sixteenth Finance Commission (XVI FC) has recently finalised its recommendations and will submit its report on schedule in October 2026. The chairman is quoted saying that no significant increase in devolution to states is contemplated.

The process of appointing a finance commission is not a consultative one. The Prime Minister appoints the members and chairperson. The central finance Ministry drafts the terms of reference. This administration has been parochial in its appointments to the commission. The Fifteenth Finance Commission (XV FC) comprised an IMF bureaucrat, an economist-turned-BJP politician and civil servants. There was no representation from the peninsula. The XVI FC follows the same pattern, with just one civil servant from South India, whose career has been spent entirely in New Delhi, serving the central government.

Only the terms of reference (ToR) of the XVI FC seemed to indicate that things would not be business as usual, given the emergent contentious issues. It dispensed with the usual gaggle of meaningless supplementary asks (the XV FC’s ToR was particularly egregious on this score, drafted by civil servants with little knowledge of fiscal federalism and endorsed by an inexperienced and clumsy political leadership) and wanted the commission to focus on the core issue of vertical and horizontal devolution.

This unusual brevity and precision on the part of the Government of India recognises a formidable challenge confronting intergovernmental fiscal relations. It is unlikely that the southern states will passively accept the findings of the XVI FC as nonpartisan. What this lack of acceptance means in practice is unclear, as the Centre can override any dissent to adopt the commission’s recommendations once its report is placed in parliament.

Nevertheless, it is wise not to use parliamentary procedure that works in times of national consensus to ride roughshod when there is serious political dissonance. There have been conclaves of non-NDA southern chief ministers and considerable public debate that has underscored the point that “business as usual” would be unacceptable.

The root of this uneasiness lies in the evolution of a structural break in the country’s patterns of economic transformation, which has accelerated significantly over the past 30 years. The relative per capita income of the northern and eastern states has declined, while that of the peninsular states has risen. Human development achievements of the latter have far surpassed those of the rest of India. The peninsula now imports both capital and labour from the rest of India, accounts for most of India’s non-commodity exports and is the major destination for foreign investment. Other than Delhi, all metropolitan growth has occurred in the peninsula. All sunrise industries—IT, Pharmaceuticals, light engineering, FMCG, and automobiles—are preponderantly located in the peninsula.

However, there is another skew which impacts the balance of political power. Fertility in the peninsula has declined sharply relative to the rest of the country. This means the population share of southern India is now much lower than it was in 1971. In combination, this is a potentially explosive situation. Few countries have managed to navigate this asymmetry of a political majority being vastly poorer than an economic minority. Without convergence or an innovative political settlement, this is an existential threat.

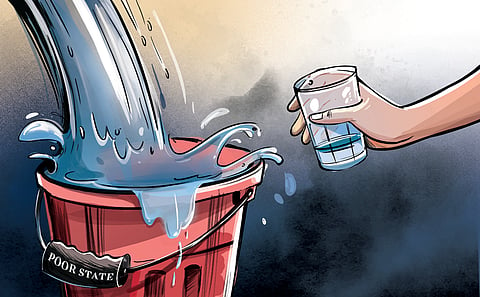

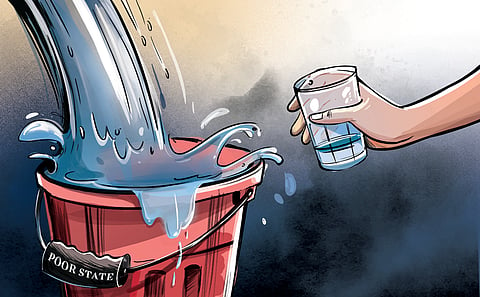

The finance commissions have been the only instrument to mediate this conundrum with an implicit grand bargain. The poorer states have benefitted hugely from the transfer of taxable resources from the richer states. This happens because the largest weight in the horizontal devolution formula—which determines how much each state gets from income taxes, import duties and GST—is the inverse of the state’s per capita income, which means the poorer a state is, the more resources it gets.

It is a testament to India’s federal solidarity that this has been accepted without complaint by the richer states for the past 30 years. The unspoken obverse of the political bargain was the population component of the devolution formula would be calculated using the 1971 numbers, and seat apportionment in both houses of parliament, too, would be based on the 1971 population.

However, things are different now. The richer states have been asking: Why has there been no convergence despite such a significant resource transfer from the peninsula for over 30 years? When does solidarity in anticipation of convergence turn into a permanent subsidy? Why is delimitation happening now, with a conveniently postponed census that will be used to fix relative parliamentary strength, possibly as soon as the next election? Why was the XV FC asked to use the latest census in determining its award?

Add to this the contemporary tension of an ascendant ruling party in Delhi, with its base in the poorer states, allegedly misusing its governors to subvert political decisions made by southern states, seemingly seeking to impose Hindi as a national language and aggressively (if unsuccessfully) promoting regional leaders to challenge the dominant political consensus with its own brand of nationalist Hindutva politics, and the stage is set for an apocalyptic showdown.

The XVI FC cannot, therefore, pretend that it is business as usual. This is not why they were given a broad mandate to focus on devolution issues. Given that it is appointed by the Centre without consulting the states, given the consistent anti-peninsular bias in its composition, and given that the Government of India can adopt its recommendations without the concurrence of the states, it is (rightly or wrongly) also significantly exposed to the charge of partisan conduct. It is, therefore, very worrying when the commission’s chairman is quoted as ruling out certain options (such as a sharp increase in devolution to states) in the public domain months before the award is placed before parliament.

There are many options available to the XVI FC if it has the independence and technical competence to consider them. And I sincerely hope that this is where their focus is, insofar as their abilities allow. However, pusillanimity and businessas-usual thinking, along with throwaway comments to the media (which does not befit a non-partisan constitutional body), are unhelpful, irresponsible, and damaging at this delicate juncture when intergovernmental fiscal relations are already under strain from larger pressures caused by economic and political divergence.

Rathin Roy is a distinguished Professor at Kautilya School of Public Policy, Hyderabad; Visiting Senior Fellow, Overseas Development Institute, London

(Views are personal)

(rathin100@gmail.com)