Last year, when R Balsubramanium’s book, ‘Power Within: The Leadership Legacy of Narendra Modi, was launched, one of the reviews pointed out that “while Western thought on leadership is trait-oriented, [emphasising] the importance of ‘being a leader’, Indian leadership offers a contrast—it focuses on the ‘exercise of leadership’.” The book looks at this practice as it captures Bharat’s civilisational wisdom through lived experience.

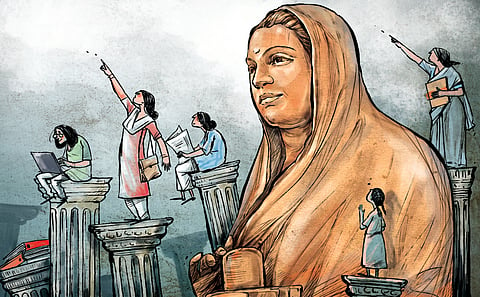

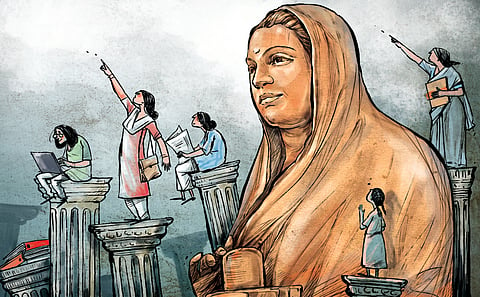

One such example of the ‘power within’ in India comes from the life and mission of Ahilyabai Holkar, the 18th century queen of Malwa, a princely state in today’s Madhya Pradesh. On May 31, the nation celebrates her 300th birth anniversary.

One of the new concepts aggressively propounded by Modi—but rarely discussed elaborately by opinion makers—is women-led development. The concept reflects an innovative, 20th-century approach as it mirrors the need for Indian society to graduate from empowerment of women to recognising their leadership.

Women-led development is not just about egalitarianism; it also carries another strong message. Men must realise that more Indian women than ever are in the driver’s seat, and that they have to ensure equality. Ahilyabai Holkar stands as a powerful symbol of both women-led development and governance.

India has a long list of queens who demonstrated valour and leadership in governance. Such exemplary women can be found across the country—from north to south, and east to west. However, it is rare to find a female leader who not only had a firm resolve to uphold Indian values, but also combined courage and strength with strategic thinking, and pursued a lifelong mission of public service. Ahilyabai Holkar was one of those rare personalities in whom we witness the unique confluence of calibre, courage and compassion.

Contemporary politics in India is under the thick shadow of dynasticism. Most dynasty-driven political parties are known for special privileges enjoyed by the next-gen dynasts. As against this, history tells us as to how Ahilyabai severely reprimanded her son Malerao for illegally killing a calf. For her, the rule of law was supreme, and she chastised her son for a serious transgression—something the present-day leaders of dynasty-driven parties can learn from.

The very mention of Ahilyabai evokes memories of her historic, nationwide work in temple construction as well as their restoration after being destroyed by aggressors. Temples built by her adorn key pilgrimage sites in several Indian states. But her temple construction was not merely a public project—it symbolised the externality of the Indian spirit of endurance, coupled with self-confidence and resilience.

Through the temples she built, Ahilyabai articulated an unwavering resolve to preserve cultural identity. For her, reconstruction of destroyed temples was not just installations of deities, but in a deeper sense, the consecration of national consciousness, too. She is also credited for building ghats, keeping both the aesthetic as well as utilitarian value in mind—as can be seen along several river banks across the country.

Though she formally ruled for only two years, Ahilyabai also constructed reservoirs, ponds and water bodies. She created a separate department of water conservation in her government. She was also one of the few rulers who paid adequate systemic attention to making farming an economically viable proposition. Her administration not only encouraged farming in multiple ways, but also tried to promote farm-based enterprises.

She distributed government land to poor farmers, though with conditions—they had to plant nine fruit-bearing trees along the edges of every unit of their fields for personal use, and 11 more whose produce would be deposited into the state granaries. As a skilled administrator, she institutionalised this through what became known as the ‘Nine-Eleven Act’.

The 18th-century monarch knew that prosperity of the people was rooted in a robust economy. During her reign, the size of her kingdom’s economy is estimated to have grown by more than 40 percent, strengthening the region’s financial health. Conscious of the fact that traditional artisans across the interior parts of her state were a backbone of the economy, Ahilyabai established a separate artisan colony in Ambad tehsil (now in Sambhajinagar district of Maharashtra), providing artisans with necessary infrastructure and access to low-interest loans.

A prudent ruler who understood basic economic principles, her investments in infrastructure hugely contributed to galvanising the economy of her state, which had suffered from wars. What was more remarkable was her understanding that even in economic matters, the modern approach has to walk hand-in-hand with age-old traditions, and that neither of the two could be ignored.

Ahilyabai was also known for approaches to several social issues that were far ahead of her time. After her husband’s death, after some debate, she decided not to observe the practice of Sati in response to an appeal from her in-laws. She was keen to ensure that widows were not discriminated against while she was regent.

She painstakingly ensured marginalised tribal communities like the Bheels were neither persecuted nor did they persecute others. Her efforts for the effective inclusion of Bheels into the socio-cultural mainstream eventually ensured their peaceful co-existence and non-tribal communities in parts of Malwa.

Ahilyabai Holkar’s vision was so timeless, her perspective so enduring, that her thoughts and actions remain relevant even today. In one of her writings, she eloquently emphasised the importance of purity in every walk of life. She wrote, “Bathing purifies the body, meditation purifies the mind, and charity purifies wealth.”

No wonder that Ahilyabai earned the admiration not just from her Indian peers, but also renowned historians in later centuries. John Keay, a bestselling British historian, described her as a ‘philosopher-queen’. John Malcolm, a Scottish scholar and diplomat, extolled her as “one of the purest and most exemplary rulers”. Historians must note that when the modern concepts of good governance were not even around, Ahilyabai took them to heart.

Vinay Sahasrabuddhe

Senior BJP leader

(Views are personal)

(vinays57@gmail.com)