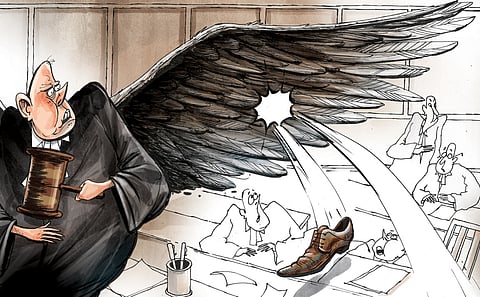

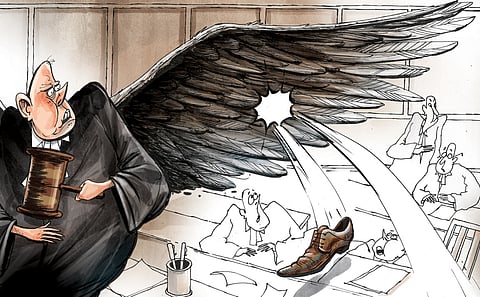

On October 6, lawyers in the Supreme Court were apparently perturbed when an advocate abruptly hurled a shoe at the Bench led by the Chief Justice of India. Yet, the CJI and Justice K Vinod Chandran remained calm and continued the proceedings. The act was purportedly a token of protest against the CJI for certain remarks he had made while hearing a public interest litigation. The PIL was for restoration of a statue of Lord Vishnu at Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh.

The Bar Council and the Supreme Court Bar Association acted promptly and suspended the advocate, effectively blocking his practice at least for the time being. Of late, sanction for prosecuting the advocate for criminal contempt has been granted by the attorney general.

Such incidents are, however, not unprecedented. It is heard that decades ago, another CJI in the Supreme Court faced a similar situation with shoes thrown upon him. He then ordered the return of the shoes to the litigant, saying that he who lost the case should not also lose the shoes!

In the UK in the 1960s, when books were thrown at a Bench comprising Lords Denning and Diplock, they refused to take action for contempt against the woman, earning praise from her as she was being led away. However, in 2009, in another disturbing incident, a woman who threw a slipper at a judge of the Supreme Court of India was immediately taken to custody and proceeded against.

Unlike these events, the latest assault was not by a disgruntled litigant, but by a person who was part of the institution, a citizen who was supposed to uphold rule of law. The motive was not merely personal but also ideological. The event, in a way, shows India’s ‘Capitol moment’ in a singular form. It was a clear attack on the supreme seat of constitutional adjudication; an attempt to demolish something more fundamental for the nation’s existence.

The SCBA said the incident is a direct slap on the independence of the judiciary. The act amounts to in facie contempt, or contempt on the face of the court, apart from a few other offences enumerated under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023. The conduct of the advocate outside the court—justifying the act and again accusing the CJI—might invite action for ex facie contempt as well.

But there are more serious issues behind the incident that stare at the future of our republic. The attitude, the audacity, and the total lack of repentance from the advocate who did the mischief makes a compelling case for an analysis into the divisive ideological trends surrounding us.

The PIL, on the face of it, did not involve any issue warranting judicial interference in the constitutional sense, since the prayers made were out of the purview of the court’s writ jurisdiction under Article 32 of the Constitution. At best, those would fall within the policy domain of the executive. The plea could have been crushed at the threshold by any Bench. An advanced democracy would have had a discourse on the CJI’s judicial behaviour in such a situation. The open statement subsequently made by the CJI that he treats all religions with equal respect ought to have given quietus to the entire controversy.

To say that the CJI invited trouble by his remarks is casual and irrational. Such a view, expressed even by a former judge of the Supreme Court, is dangerously superficial and inherently problematic. Even judicial aberrations from the Bench can only call for people’s criticism and not physical assault.

As Lord Atkin famously put it: “Justice is not a cloistered virtue, and therefore, must be allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful, even though outspoken comments of ordinary men.” Yet, the social media backlash following the Vishnu idol case hearing was neither civilised nor respectful. In a way, what happened in the open court on October 6 was an aggravated and crude extension of this mindset, which requires to be condemned in the strongest terms.

The incident signifies gradual collapse of rule of law that has been taking place for quite a long time. The country faces a new normal where hate speeches and hate crimes are encouraged often by the State, and genuine dissent is criminalised and dissenters incarcerated by the very same State. Selective use, misuse, and non-use of law is a striking feature of a country losing its grip on rule of law.

The Supreme Court’s pronouncements on hate speech and hate crimes as made in Tehseen S Poonawalla (2018), Kodungallur Film Society (2018) and Amish Devgan (2020) were ignored by a mighty and partisan executive. Its directive to register a first information report on every incident of hate crime also met almost with the same fate. Calls for genocide became the new normal in our public life.

On the other hand, when the political dissidents were jailed indefinitely, the Supreme Court often remained a helpless onlooker. This paradox of the Indian legal system was abetted by the diminishing number of public intellectuals from among the legal fraternity. The incident in the CJI’s court needs a reading between and beyond the lines. It motivates us to deconstruct the present situation.

India, as a nation and society, has grown up through dialogues. Though the society essentially remained caste-ridden and hierarchical, there have also been finer streams of Hinduism that encouraged fearless discussions.

With the advent of constitutional democracy, we tried to replace the clashes with dialogues and bloodshed with handshakes. Freedom of expression under Article 19(1)(a) became the cornerstone of India’s deliberative democracy. Fraternity, the most vital constitutional value, is significant for any democracy to carry forward the conversations.

The CJI’s reaction—of ignoring the attack, remaining unaffected, and pardoning the man—was not a tactical or procedural gesture. It was not merely a matter of magnanimity either. It was a deeply spiritual act, perhaps the best possible answer to a culture of violence and intolerance based on religious fanaticism. In the process, the CJI had an enormous moral victory.

The incident demands conscious efforts for revitalising India’s republicanism at the institutional and people’s levels. It tells us about the need for reasserting dignity for all sects of people, including Dalits and minority groups at various levels—from the streets to the highest constitutional offices. Those who try to substitute dissent with duress and dogmatism always remain on the wrong side of history.

Kaleeswaram Raj | Lawyer, Supreme Court of India

(Views are personal)

(kaleeswaramraj@gmail.com)