From space to consciousness: Indic architecture-II

What is the ultimate purpose of architecture? Is it mere utility or a lasting human validity? Dividing our experience of the world into interior and exterior, what does the act of building effect in human terms? A separation or continuum? A split or equipoise? Alienation or belonging? This series explores two central architectural concepts from early India, mandala and mandara, in which form and spirit fused synergistically with a view to transcending divides and transforming the partaker. In metaphysical terms, the hrdayakasha (human heart) and paramakasha (cosmos) or the individual atman (soul) and universal brahman (pure consciousness) mirrored each other, and true knowledge was the realisation of their unity. So Indic architecture too, at its highest, became a meditation on the true nature of reality, which led to liberation.

How did this happen actually? One of the powerful techniques evolved for this was the concept of vastupurushamandala. Note the homology between the human body (purusha) and architecture (vastu)—an understanding of space in the image of man, a parallel that extended between the body and the universe too, as we will see. The mandala is a square grid design or plan consisting of 64 or 81 squares radiating outwards from the centre, on which ritual altars, temples, chaityas, houses, palaces or cities were meant to be founded in early Indian architectural thought. It is a configuration of square base, surrounding enclosure with apertures/exits, and a real or projected vertical axis.

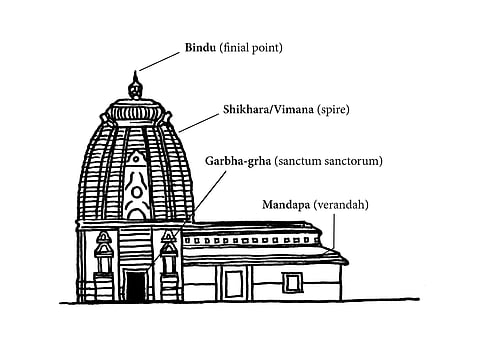

In the temple specifically, this “axis of access”, as Michael Meister called it, was visualised stemming from the mandala’s centre, the sanctum called garbhagrha (womb), guha (cave) or hrdaya (heart). It rose through graded tiers till as high as the devotee’s vision could rise, to form a spire called shikhara (peak) or vimana (tower), culminating in a finial or summit called bindu (point).

The bindu served literally as the point of contact between the immanent, concealed, recessed consciousness deep within the garbhagrha or hrdayakasha on the one hand and the transcendent expansive infinite consciousness without, i.e. the brahman or paramakasha on the other. The temple plan thus symbolised the “descent and ascent of consciousness”, to quote R Nagaswamy, and provided for the merger of exterior with interior, or of eternal consciousness with that of the devotee. Duality was thus overcome, reality was thus realised. Further, it is by the spatial plan of the temple, via the mandapa or verandah that led straight up to the sanctum, that the devotee was inexorably drawn to the garbhagrha to experience this self-transcendence.

As if that wasn’t transformative enough, the temple also served as a participatory creation myth. The reference to purusha harks back to the celebrated Vedic Purusha Sukta or creation hymn, wherein the cosmos was born from the body of the primeval or supernal man. But “in the beginning was darkness, swathed in darkness; all this was but unmanifested water,” as the Rig Veda Samhita (X.129.3) narrates. From this cosmic ocean of darkness, using the inverted heavenly mountain named Meru or Mandara, the gods and demons conjointly churned into existence all of creation. Mount Mandara is veritably the axis mundi, then, that rent or pillared apart the heavens and the earth, holding up the former, connecting it to the latter, and lending to the Hindu temple its name, mandara, and its analogy with a mountain.

Here is, interestingly, how the astrophysicist McKim Malville describes the experience of entering a temple:

“Moving inward in space and backward in time, one proceeds from brightly lighted exterior space to darkness, from large open spaces to confined small space, from richness of carving and decoration to the simplicity of the unadorned centre … Enshrouded by a darkness pierced only by a few lamps, lies the garbhagrha … symbolic of the chaos, potentiality and undifferentiated wholeness out of which the universe emerged. Spreading outward from the centre along cardinal and intercardinal directions, the stones of the temple [and the rich iconography on them] symbolise the [diversity of] creation into which the universe transformed itself.”

The underlying unity is never lost thus. As the Katha Upanishad tells us: rupam rupam pratirupo bhavuh (the formless takes many forms). Further: “Decorated with symbols of water like images of Ganga and Yamuna, the doorway of the [womb chamber] is a transformational symbol, like water itself. When entering … the devotee undergoes a transformation and a death: He dies to time. For he can travel back in time by moving to the temple centre, and experiencing or re-experiencing [there] the birth of the cosmos.”

The temple plan thus set eternity in motion, as it were! Can there be a more profound reminder to humankind of being at one with creation? And can there be a more powerful argument for overcoming the fragmentation and alienation that plague modern humans and society?

What may we take away from all this? One, we must acknowledge the transcendent potential of architecture and the veritable power of built space when it is true to, and in harmony with, qualities of the human spirit in equipoise. Therefore modern architecture must discover meaning and purpose that are greater than itself. And two, we must infuse contemporary building practice with culturally specific possibilities and solutions to the perennial problems of the human condition.

In other words, we must restore to the practice a communitarian knowledge and vision of a better way of life. Far from a contradiction in terms, early Indian architecture appears to have been meant to overcome contradictions of the inner and the outer, the subject and the object, mind and matter, unity and multiplicity. It was meant to recuperate the whole. Let architecture be meditation once again, and heal and make whole again.

(Concluded)

Shonaleeka Kaul

Associate Professor, Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University

(The author is editor of ‘Eloquent Spaces: Meaning and Community in Early Indian Architecture’)

(shonaleeka@mail.jnu.ac.in)