The Barabar hills in Bihar’s Gaya district contains a unique group of man-made rock-cut caves (3rd century BCE) of great historical value and architectural and sculptural significance. At least three caves of the hill were surely excavated by Piyadasi i.e., King Asoka (r. c. 268–232 BCE) of the Maurya Empire. The caves of Sudama and Visvamitra were created in the 12th regnal year of Asoka, and the Karna Chaupar was made in his 19th regnal year. But the Lomas Rishi cave remained unfinished and hence also contains no edict of Asoka. However, the ground plan of the Sudama and Lomas Rishi caves are nearly identical, and therefore, many scholars consider the latter one to be also excavated during the Asokan period, probably sometime in the last 20 years of his reign. Further, in the nearby Nagarjuni hill, Asoka’s grandson, Dasaratha (r. 232-224 BCE), had also excavated three caves on the occasion of his accession to the throne at Magadha (Patna), with each one bearing his edict. These three caves are known as the Gopika, Vadathi and Vapiya.

All the caves of the Barabar and Nagarjuni hills were donated as dwellings to Ajivika ascetics. It was an ancient Indian religion that however completely vanished after the 14th century. The religion was founded by Goshala Maskariputta, who was known to be a contemporary of Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism, and Gautama, the Buddha of Buddhism. Though nothing is known about the religious practices of the Ajivikas, K R Norman, an expert on Pali literature and the Asoka edicts, has said that these ascetics had worshipped the elephant. In this context, I take liberty to add that the name of one hill, naaga-arjuni, points to the divine White Elephant; for, the naaga means an ‘elephant’ (and also a ‘serpent’), and arjuna means ‘white colour’. In fact, the Barabar hilltop, divided into halves, appears like a pair of elephants that face each other while leaning onto the ground. The same natural feature, in my opinion, would invariably explain the name, baraabar, which means ‘on par with one another’.

The Lomas Rishi cave remained unfinished most likely because of certain technical problems like the appearance of large cracks in the granite stone while the excavation was still in progress. The interior of all the caves, including one side of the Lomas Rishi, have been finely polished, a typical feature that is well-known as the hallmark of Mauryan art, as seen in Asoka pillars topped with the capital basements that bear animal figures like the elephant, bull, lion and perhaps also a horse. Visitors to the cave have remarked that the finely polished interior stone surface reflects every figure and form in front of it, almost like a mirror.

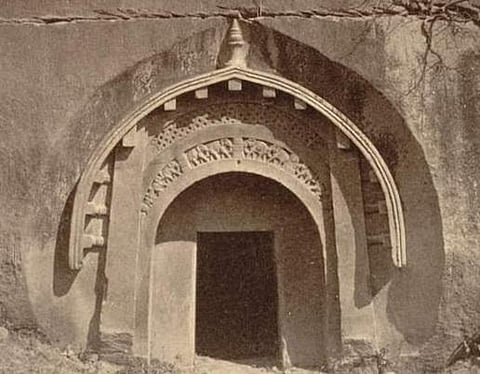

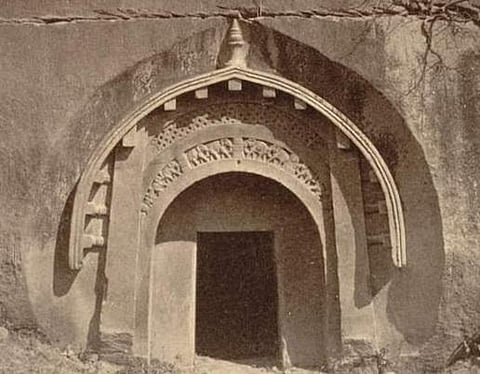

Of all the rock-cut structures, the Lomas Rishi cave stands apart, mainly because of the dwaara-torana (doorway embellishment), which has been carved with refined figures in relief. The motif of makara (crocodile) has been carved prominently on either end of the torana. These makaras appear almost like crocodiles with just a suggestion of a horn on the snout and with a reptilian tail having spines. Further, a row of 10 elephants are shown paying their homage to the stupa. The overall shape of the entrance is usually described as like the horseshoe, but more aptly as the gaja-prista-aakara (in the shape of an elephant’s back). The arch is single-pointed with the lock knob at the top centre; a row of beams are carved as support below the arch, and many crisscross strips are also carved to suggest a window in between the arch and the panel with figures. Such architectural features clearly reflect the wooden buildings that were in vogue during the time of Asoka, and even perhaps earlier.

In India, the Barabar caves are the first known examples of rock-cut cave structures and led to the making of many similar monuments all across the country at a later period. The dwaara-torana of the Lomas Rishi cave later on evolved into various types of makaras—comprising parts of a crocodile, fish and elephant—and also the makara-torana that is around various iconographic representations of many divinities of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.

British novelist E M Forster worked as private secretary of Tukojirao III, the Maharaja of Dewas in Madhya Pradesh, and seems to have either read about the Barabar caves or even visited them. He had introduced the caves in his novel, A Passage to India (1924), but under the fictional name of Marabar caves, where a significant event in the novel takes place. The incident in the movie (1984) of the same name, as far as I know, was filmed at Savandurga and the Ramadevarabetta caves near Ramnagar in Karnataka, but not at the Barabar caves.

Srinivas Sistla

Associate professor, Department of Fine Arts, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam

(sistlasrini@gmail.com)