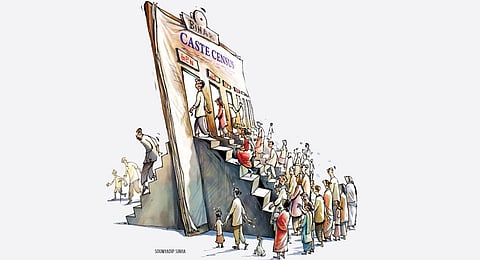

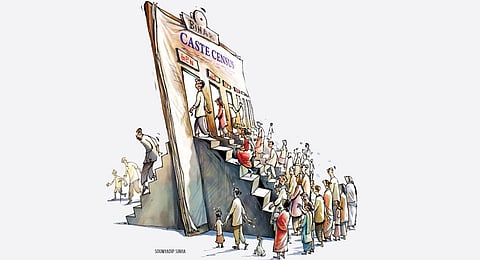

Questions about a caste-based census surfaced regularly in parliament for nearly two decades. The standard response till date has been: “The Government of India has not enumerated caste-wise population other than SCs and STs in the census since independence.” The wall of ambiguity faces a politically challenging circumstance.

This week the government of Bihar set the cat among pigeons, unveiling the results of a survey of castes in the state. The findings of the ‘Bihar Jaati Adharit Ganana’ triggered a tsunami of reactions. The Bihar essay has reignited the debate on castes and quotas across India’s social and political faultlines. The absolutes and ratios underlined by the survey have awakened hopes and triggered fears.

Unsurprisingly, there is a chorus from the Opposition for a national caste-based census. The “if, how and when” of such a census would depend on the trajectory of politics and stance of parties. The issue is already fodder for raucous rhetoric and will be debated through the assembly polls and the 2024 elections.

It is instructive that caste continues to catalyse political passions seven decades after independence and three decades after adoption of the Mandal Commission recommendations. To appreciate the centrality of caste in the political economy one must separate the signal from the noise. Yes, there is no disputing the quest to reshuffle the social and political hierarchy. But above all, the clamour signals distress at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid.

Data illuminates and rivets the cause and the consequences. Consider the architecture of India’s economy. Agriculture accounts for 18.3 percent of GDP and employs over 45 per cent of the workforce—simply put, nearly half the workforce depends on one-sixth of the national income. The average size of operational holdings is barely 1.08 hectares and has eroded yield and income. On August 1, the government informed parliament that the average monthly income of agricultural households across India was Rs 10,218—Rs 4,895 in Jharkhand, Rs 7,542 in Bihar and Rs 8,061 in Uttar Pradesh.

The calls for a fair share of quota are not limited to backward classes. Even those viewed as “landed” and powerful—the Marathas, Patidars, Jats, Kapus—have in recent times agitated for a spot on the quota map. Driving this demand is the eroding viability of agriculture as an enterprise. The correlation between dependence on the rural economy and low per capita income is stark. The per capita NVA (net value added) for rural areas, at Rs 40,925, is less than half that for urban areas at Rs 98,435.

The gap between industrialised and agrarian states is reflected in national data. India’s per capita income is Rs 196,983. Topping the list is Telangana at Rs 308,732—followed by Karnataka at Rs 3.01 lakh and Haryana at Rs 2.96 lakh. In glaring contrast, per-capita GSDP in Bihar is nearly a fourth of the national average at Rs 54,383; that of Uttar Pradesh is Rs 79,396 and Jharkhand is Rs 80,060. The impact of lower income and resultant inequality is manifest in asset ownership. The 77th Round NSS report on debt and investment reveals that the top 10 percent of households owns over half the assets while the bottom 50 percent owns less than 10 percent of the assets.

The landscape of need is illustrated by the expansion of welfare. The rural employment scheme MGNREGS was legislated in 2005 to bridge the gap between hope for employment and reality. In 2023 it has over 26.59 crore registered workers. In the past three years, average outgo on MGNREGS has been around Rs 1 lakh crore - total expenditure since inception has been over Rs 9.68 lakh crore. The National Food Security Act is 10 years old. This year, the government has allocated about Rs 2 lakh crore to provide free rations to 81.35 crore individuals. Add programmes administered by states—from old age pensions to cash payments to women. The National Payments Corporation has as many as 7,517 codes registered for direct payment transfers.

Characteristically, young India views a government job via quota as the way out of the rut of doles and poverty. The aspiration is challenged by a curious Indian paradox—the coexistence of joblessness and vacant government posts—perpetuated by political apathy. It is estimated that there are over 2 million posts vacant across central and state governments. This July, the government informed Rajya Sabha that there are 9.64 lakh posts vacant across departments in the central government. Add to this over 12 lakh teacher posts—there are 117,285 single-teacher schools across India—and those of healthcare workers and police personnel left vacant across states.

It is true that addressing asymmetries of opportunity and income calls for a reconfiguration of the current paradigm of reservations. It is equally true that the exercise cannot stop at merely identifying those in need. Diagnosis alone is scarcely sufficient to heal the polity. The parties chorusing the demand for enumeration must present a credible policy prescription—for modernising agriculture, for investing in human capital, for employment generation—to propel growth and harness demographic dividend. The quest for equity must be enshrined in the altar of an ambitious plan for growth without which quotas will at best represent a post-dated promise.

Shankkar Aiyar can be reached at shankkar.aiyar@gmail.com