Farmers cultivate the land to feed the people. Politicians cultivate the farmers to rule the people. This divergence of interests has been the cause of farmers’ revolts in India from the Indigo revolt to Champaran satyagraha, the Bardoli Movement to the Telangana Peasant Revolt, and now.

The ongoing farmer’s unrest reflects the growing chasm between India and Bharat. Both perceive development through their own prisms. Citizens attached with the soil do not understand the grammar of the urban dominated decision making mechanism. India’s quest for rural growth has been reduced to a confrontation between Farmers and the Rest.

The numbers of protesters at Delhi’s gates may be numerically minimal compared to their 150 million brethren across India, but their voice is being heard across the country as well as found empathy with global icons. Despite the massive headlines and prime time gabfests, the farmers’ revolt of 2021 could fizzle out like many others in the past. Not because of the legitimacy of their concerns but because of the system’s contempt for the colour and culture of farmers’ leadership, which has rural pedigree but lacks the urban sensibility that provides negotiating skills.

The sit-in at the capital’s entry points over the past 100 days mainly by Sikh and Jat farmers of North India are fully supported with financial and logistical support by those opposed to the Narendra Modi establishment. The farmers are inflexible in their attitude and intentions. They want the complete repeal of the three farm laws passed by Parliament.

On the face of it, the laws provide the farmers with better access to markets for their products, better technology and better chances to change the cropping pattern for earning better. But they are convinced that these measures are meant to corporatise agriculture and to deprive them of a MSP. Several rounds of talks between their leaders and Union Ministers haven’t yielded results. They just meet to meet again. The standoff between democratically elected leaders in power and the people who claim to represent lost voices drowned in the cacophony of agro reforms, continues.

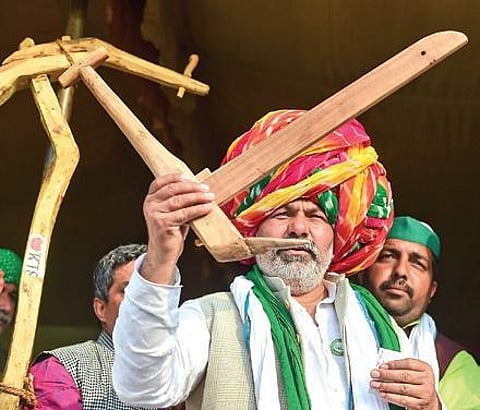

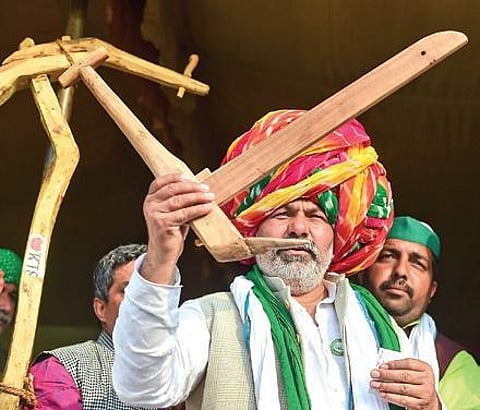

The occasional farmer agitation in various parts of India has been an integral part of national democratic architecture. Even without a defined pan- Indian leadership, farmers from the South to the North have hit the streets seeking better financial assistance and favourable trade terms. Tragically, the farming community that represents over 60 per cent of the Indian population are unable to convincingly put forward its case to the government. The insurrections are not only divided on a regional basis but lack a plausible agenda to make agriculture a viable profession. Farmers lack social and intellectual craft to communicate using a medium and manner that the system gets. The likes of Rakesh Tikait leading the current agitation are, at best, experts of crowd collection.

Because of North India’s larger geographical farming area, its peasant leaders acquired brief national prominence in their ideological struggle supporting rural India. However, no peasant leader has acquired enduring national status. Chaudhary Charan Singh was not a tiller himself, but he was an intellectual. He rose to become the first and, perhaps, the last genuine dhoti clad Kisan leader, but is still known more as a defector than a farmer leader. Later on, Devi Lal, another ferociously aggressive rural leader, became Chief Minister of Haryana first and India’s Deputy Prime Minister later. Neither were accepted as national leaders. In contrast, Sharad Pawar, a farmer first, is adored by the urban elite for being market and technological savvy.

Agrarian crises have become vertically serious because policy makers never gave peasant issues the attention they deserve. Reforms for new India have been loaded against the rural sector. Four decades ago, agriculture contributed over 50 per cent of the GDP; now it is barely 15 per cent. India has had 33 agriculture ministers since Independence with 25 of them coming from rural backgrounds. Half of them like Swaran Singh, Prakash Singh Badal, Devi Lal, Balram Jhakar etc were from north Indian states. None of them pushed major agrarian reforms. The credit goes to Bharat Ratna C Subramaniam, a South Indian who made the Green Revolution a reality along with MS Swaminathan.

Farmers’ fury doesn’t reflect the agony of any caste or region. It cuts across the communal and caste divide. A reason could be genetic origin of Indian farm uprisings. The history of Indian peasant agitations go back to colonial times when the British disrupted Indian landholding patterns, driving a thriving agricultural system into the fatal arms of famine.

The Kisan Sabha movement of 1929, formed by Swami Sahajanand Saraswati took on zamindars against forcibly occupying peasant land. The revolt became an all India movement and the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) was born. Over time, Socialists and Communists took it over. Communists mastered the art of organising mass protests by marginal farmers.

The violent Telangana Revolt 1946-51 against the Nizam and zamindari repression helped the Left parties to create an electoral base in the region. Simultaneously, the Communist Party of India launched the Tebhaga movement in West Bengal through AIKS to minimise the landlord’s role in distribution of agricultural produce.

These agitations were ideologically and not personally led, and, hence, couldn’t produce a national peasant leadership — the fact that the Swami is not even an active part of Indian history is proof of the inefficacy. During the early 1970s, the Shetkari Sanghthan was launched in agrarian distress-laden Maharashtra under the erudite and suave leader Sharad Joshi. He too is restricted to the peasant pantheon. For the first time, farmers demanded remunerative prices for their products under him. Since then only local satraps have been leading farmers to taking up regionspecific issues.

Market-led economies like India have little place for players from Bharat. Interestingly, 38 per cent of the 542 current Lok Sabha MPs are agriculturists by vocation as against 20 per cent in the previous Lok Sabha. Yet their collective wisdom hasn’t bettered the lives of their own. For them, perhaps good rural politics is bad urban economics. Sadly, agriculture is becoming the least preferred profession for rural Indians who are migrating to cities for not just jobs but also recognition.

However, looking at the geographical spread of rural unrest, it is evident that Bharat is rising ferociously to resist further erosion of its economic and political clout. If farmers choose to vote like kisans in every state, they could acquire a decisive say in governance, and even a national leader of their own. The Colonisation Bill of 1906 passed by the British allowed the colonial government to take over the property of anyone who died heirless. It could be sold to developers. Incidentally, it was soldiers of the Jat paltan who revolted first. Peasant rebellions cannot be underestimated where land is concerned. Politics that ignore the maxim ‘you reap what you sow’ may find itself buying the farm sooner than expected.

prabhuchawla@newindianexpress.com

Follow him on Twitter @PrabhuChawla