In 2023, world football was punctuated by two developments at either end of the calendar, and they confirmed an already visible shift away from status quo.

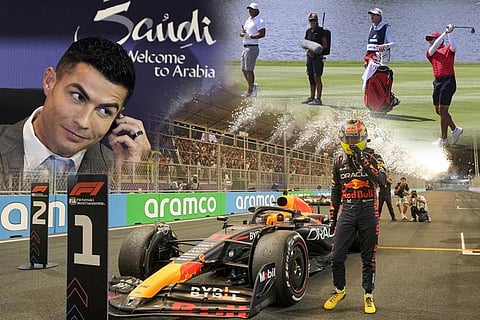

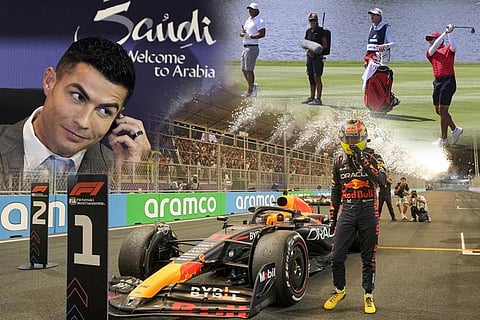

The first came just a couple of days after the new year had dawned. Cristiano Ronaldo, either the world’s most famous or second-most famous — depending on where your allegiances lie — footballer stood waving to fans, not on the hallowed turf of the Santiago Bernabeu or the Juventus Stadium, but in the little-known Mrsool Park (since rebranded the Al-Awwal Park) in Saudi Arabian capital of Riyadh. Before Ronaldo set foot inside it, the stadium’s biggest claim to fame was probably hosting a couple of WWE events. It was still being built when Ronaldo won the third of his five Ballon d’Ors in 2014 and had about a third of the capacity of Old Trafford, the ground he previously called home. Yet here was one of the greatest footballers of the modern era, clad in Al-Nassr’s yellow shirt, waving happily to his new fans.

The second was actually a series of smaller developments that happened throughout the month of October that tied into one larger endgame, not unlike how a series of bizarre clues often come together to make perfect sense at the end in a Hercule Poirot novel. On October 11, a FIFA Council Meeting chaired by its president Gianni Infantino confirmed that the 2030 World Cup would be hosted not by three countries, but by three continents — Portugal and Spain from Europe, as well as Morocco from Africa would host the bulk of the matches while Uruguay, Argentina and Paraguay from South America would stage a game each. The decision to take the tournament to South America for just three nights was explained away as a nod to Uruguay hosting the first-ever World Cup a century ago in 1930.

However, a more plausible explanation came when the same council meeting quietly confirmed that only countries from Asia or Oceania would be able to bid for the 2034 World Cup due to its rotational policy. North America had it in 2026 and now every other continent had been shoehorned into the 2030 schedule, clearly to make things easier for an Asian bid.

Then, on October 31, with just hours left for the meagre 27-day period that FIFA had allowed for bids to be submitted, Australia announced that it would not be bidding to host the tournament. That left Saudi Arabia as the only bidder and rendered a vote on the matter irrelevant. A day later, Infantino confirmed what everybody already knew via a social media post. “Three editions, five continents and ten countries involved in staging matches in the tournament — that's making football truly global!,” he patted himself on the back. He would, no doubt, have received more pats on the back when he flew to Saudi for the Club World Cup in December.

It is no coincidence that the football calendar began and ended in Saudi Arabia. Over the last few years, the desert kingdom has been quite unsubtle in its efforts to dominate world sport. In 2012, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia, bought English football club Newcastle United. Apart from hosting a Formula One race, Saudi sponsors a number of teams through their various brands. Saudi Arabia has been the host to several leading professional boxing events in recent years, including Oleksandr Usyk’s win over Anthony Joshua in 2022. And in 2022, the PIF funded the inaugural season of the LIV Golf Invitational Series, a rebel tour that managed to attract top golfing talent away from the PGA Tour.

In 2023 though, these efforts ascended to a whole other level.

***********

The flow of footballing talent to the desert sands of the Arabian peninsula continued over the course of the year. Names to make the move included Neymar, Karim Benzema, N’Golo Kante, Roberto Firmino and Sadio Mane. While leagues and clubs in China and Russia have tempted players with petro-dollars before, this was an exodus that was unprecedented. Serbia’s Sergej Milinkovic-Savic, for example, is a player at the peak of his prowess at 28 and was sought by some of the biggest clubs in the world just the season prior. Aymeric Laporte, one year older, was coming straight off winning the English Premier League with Manchester City and being described as one of the best defenders in the league.

It was not just players that the Saudis managed to attract. Among the tournaments that they brought to their shores in 2023 — apart from the 2034 World Cup — are the FIFA Club World Cup and the Italian Super Cup. Football, though, was just one of the many cogs in the machine. The Saudis won one of the biggest sport victories in golf when it was announced in June 2023 that the rebel LIV Golf funded by them would merge with the mainstream PGA Tour. This was significant for the mainstream golfing world’s initial reaction to LIV Golf was to threaten participating golfers with all kinds of sanctions. The move to pool resources with them was a tacit admission that they were powerless to resist the winds of change.

“It is an exciting day,” said PGA Tour Commissioner Jay Monahan when the merger was announced. “To be able to take an aggressive competitor over the last two years and have that entity be a productive minority investor and for us to all be aligned, is very exciting." This was quite the change of tune from a man who had earlier said that golfers leaving for the LIV Tour would have to apologise to American society, a not-so-subtle hint at the Saudi role in 9/11.

Other sports too queued up to be funded by Riyadh’s oil money. ATP announced that the season-ending Next Gen Finals for men's under-21 tennis players will be held in Jeddah from 2023 to 2027. In November, the world of boxing awoke to news that Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk will fight for the undisputed heavyweight championship of the world in Riyadh in February 2024. Then, at the end of year, came the big news that Saudi Arabia was looking to purchase a sizable stake in the Indian Premier League to the tune of $30 billion.

***********

Of course, Saudi Arabia is not the first political entity to attempt such a strategy nor will they be the last. Regardless of the outrage the last few years have generated, mainly among Western observers, the use of sports to achieve political ends is neither new nor rare. The concept of soft power, first introduced by Joseph Nye in the 1990s, has been one that has found increasing relevance in international politics in recent times. “Soft power is the ability to affect others to obtain the outcome one wants through attraction rather than coercion,” Nye wrote in one of his papers on the topic.

And sports has been used as a tool to obtain soft power since time immemorial. Wars were fought in ancient Greece to wrest control of the sanctuary at Olympia and gain the right to organise the Olympic Games. State-sponsored gladiatorial contests were a regular feature in the Roman empire, held to celebrate kings and victories. A lot closer to the present, there is Nazi Germany hosting the Berlin Olympics in 1934, Fascist Italy hosting the 1938 FIFA World Cup, the communist and capitalist Olympics Games of 1980 and 1984, hosted respectively by the USSR and the USA.

These days, the term being bandied around to describe this phenomenon is sports-washing. That term brings with it a moral connotation and became mainstream usage when Russia and Qatar won the rights to host the 2018 and 2022 World Cup, respectively. And once again, it is being bandied around with Saudi Arabia — a country where a laundry list of human rights abuses have been committed in recent times.

While acknowledging this reality, it has to be noted that outrage for the moral gatekeepers of this world is often selective. Sportswashing was not a term used when London was selected as the host of the 2012 Olympics in 2005, or when David Beckham moved to LA Galaxy in 2007, both developments coming at a time when armies of the US and UK were jointly bombing civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan. And there were only the rare voices of outrage when the 1978 World Cup was hosted by a US-sponsored military junta in Argentina, in stadiums still riddled with bullet holes from mass civilian executions. Of course, values often only come in handy when convenient. English footballer Jordan Henderson, who was quite loud in expressing concern over the LGBTQ rights situation in Qatar before the World Cup, now captains Al-Ettifaq in the Saudi Pro League.

For Saudi Arabia, neither moral conundrums, nor labels stuck on to it by Western media, will matter. Their immediate objective is to project themselves as the leader of the Islamic world, a picture of stability and prosperity in a region that has historically struggled to sustain both. And over the long term, they would hope to diversify their economy and lessen the dependence on fossil fuel. Controlling world sports is one of the many ways of achieving those twin objectives. Saudi’s crown prince and de-facto ruler Prince Mohammed bin Salman said as much when confronted with allegations of sportswashing. “If sportswashing is going to increase my GDP by one percent, then we'll continue doing sportswashing," he told Fox News.

And if 2023 was the year when the Arabian peninsula became an undeniable presence in world sports, the next couple of years might just be when it becomes its undisputed capital.