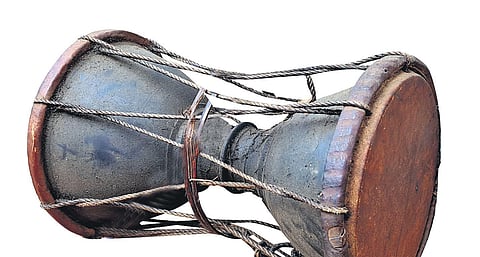

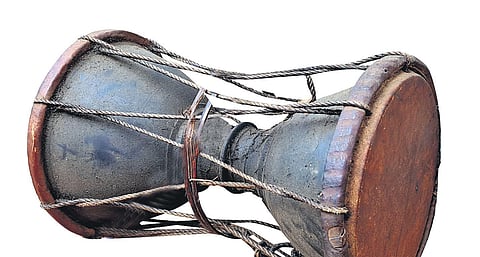

MADIKERI: Rustic and rhythmic sounds resonate in the air in the Kodagu district when Kodavas observe special occasions. These rustic sounds are from the traditional drum called the ‘Dudi’. With a metal base and the batter head made of animal hide, Dudi holds a special place in the rituals practised by the Kodavas.

While the traditional Dudis still hold a great significance among the community, the art of making Dudis is slowly dying. Today, only a handful of artisans are creating this unique instrument. Nonagenarian Subbaiah U is one of them. Elaborating on how he makes Dudis, Subbaiah says, “In the past, I used to make Dudis from the skin of muccha (lion-tailed macaques). As hunting of macaques is prohibited by law now, I use goatskin.”

First, artisans buy the hide from meat shops for approximately Rs 350 a piece and then the tedious and intricate process of making the drum begins. “The first tough job is removing hair from the goatskin. One cannot use blades as it can damage the skin. We rub the skin on a hard surface, like stones, to remove the hair and then cut it to the size of the base. We need two skins to make a Dudi,” explains 65-year-old KA Ganapathi, another artisan who has been making Dudi for nearly three decades now.

Going back to the myth and origin of Dudi, historian Bacharaniyanda Appanna says, “In the past, forest dwellers created the instrument for entertainment. It is said that they wanted to imitate the sound of the woodpecker that resonates in the forest.” Dudis were earlier made using hollow tree barks for the base and lion-tailed macaque’s skin for the resonating heads.

Ropes made from natural plant fibres were twisted around the drum and canes were used to imitate the sound of the woodpecker. Gradually, bronze replaced the wood for the base and goatskin for the head. “Now, not many work with bronze and workers who can repair bronze material are also rare. While we fix the resonating heads of old bronze bases, the new ones are created using brass,” he explains.

The cleaned goatskin is first soaked in water and then placed on an hourglass-shaped metal base. It is neatly stitched (using plant fibres) around the vertical openings of the metal base and is dried under the Sun. A ring created using plant fibres is placed on top of the skin and around the metal base. They are then stitched with ropes, which were earlier plant-based but are now made of nylon. The ropes are then carefully tightened around Dudi. “The two sides of the Dudi give a slightly different sound and they are differentiated as male and female sound,” adds Ganapathi.

The artisans of Dudi are sought after for their special work even today, but the art may soon become extinct. Dudis are extensively used during Kodava weddings, festivals and even funerals. However, these traditional instruments are now being sourced from mass production centres.

“Many times these instruments are made from plastic and are sourced from Mysuru,” confirms Appanna. The old-time artisans who put in a lot of effort to make Dudis charge between Rs 500 and Rs 700 for a Dudi and they also receive orders to repair the old ones. Philanthropists said that these artisans should be supported to revive the dying art that contributes greatly in preserving the tribal culture.