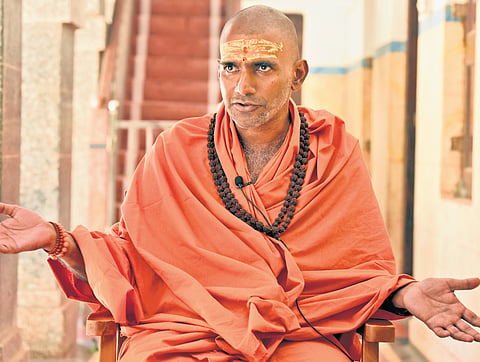

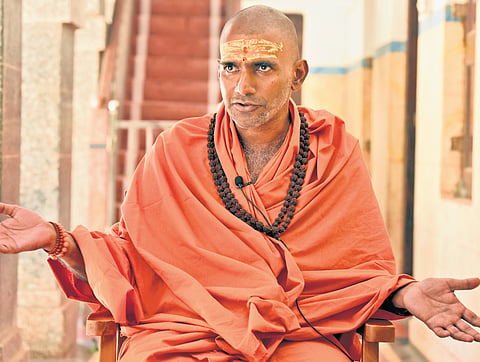

His transition from Marxism to spirituality was quite a tumultuous one. Once a firebrand student leader, P Salil grew disillusioned with communism and became a monk. Today, he is the Mahamandaleshwar of Juna Akhada, the ancient order of warrior monks. Swami Anandavanam Bharathi Maharaj, as he is known now, recently led the grand Mahamagham Maholsavam at Thirunavaya. He tells TNIE about ‘Hindu awakening’, Kerala politics, his personal journey, and more

The Thirunavaya Mahamagham turned out to be a major success — almost like a mini Kumbh Mela. Was this expected?

We had no doubt it would be a success. We believed it would regain its earlier splendour within three years, especially with the Simhastha alignment — Jupiter entering Leo — culminating in 2028. But what we envisioned over three years, people embraced in just three days. They all came to be a part of Dharma.

There are different views about its history. Some associate it with violent clashes, others as an ancient spiritual gathering…

‘Maamankam’, as it came to be known later, has no connection with “ankam” or battle. It was originally Mahamagham — the observance of the Magham month, named after the star ascendant on the full moon day in the Shaka calendar. This observance has existed across Bharat for centuries. The ‘battle’ association stems from the later conflict between the Samoothiri and Valluvakonathiri, after the former seized the right to conduct the festival. Just as some firework accidents during the Thrissur Pooram do not define the festival itself, the conflicts do not define ‘Maamankam’.

Historical accounts, including William Logan’s Malabar Manual, record that rulers were elected at Thirunavaya during Mahamagham. Palmscripts were presented before scholarly assemblies, and decisions on governance and intellectual matters were deliberated upon.

Mathematical, astronomical, sociological and philosophical ideas were debated and approved before being disseminated as literature, science and social law.

When did the idea of reviving the festival take root?

After Independence, several attempts were made to revive it — including by the Travancore kings and individuals like P Parameswarji. But they did not sustain. From 2016, Nila Puja and Ganapati Homam began under the head priest of the Nava Mukunda Temple. It continued on a small scale. It was later felt that greater involvement of sanyasis was necessary.

Who felt so?

The local priests and people associated with the temple.

Last year’s Prayagraj Kumbh Mela saw huge participation from Kerala. Was that a motivation?

That was because of better connectivity and facilities, and increased awareness. Historically, however, there is a deep connection. For instance, when the Arattupuzha Pooram takes place here, the Kashi Vishwanath temple is closed for an hour. It is believed that Lord Kashi Vishwanath comes here.

When were you approached for the Thirunavaya Mahamagham?

After the Prayagraj Maha Kumbh Mela last year, around April or May, there was an initial discussion. The matter was taken up seriously in November, as the event was scheduled for January. We had about three weeks of planning, with large-scale preparations compressed into 7 to 10 days. Considering the massive response, from next year, the Mahamagham will be held over 45 days. We will set up a base in Thirunavaya.

What were the administrative hurdles, especially regarding the temporary bridge across the Nila?

Administrative processes had begun in November. The scale of public response exceeded projections. Such temporary bridges are routinely built at Thirunavaya and elsewhere in Kerala. The official objections appeared technical. Perhaps they sought to stir a controversy to discourage people from participating.

Did you approach the government?

We had initially met the Devaswom minister, and requested him to serve as ‘rakshadhikari’ as per norm. He agreed and even expressed willingness to attend. But there was no further involvement. We did not expect any. There were no government representatives at the site. Around 200 special KSRTC services were operated, and they made good revenue. I must say the police officers and other officials on duty were cooperative.

Shouldn’t we view this as a favourable stance from the government?

No, if that were the case, they wouldn’t have issued a ‘Stop Memo’. There would have been no need to move a petition in the High Court asking for an immediate stay order. Six government pleaders pressed for it. Even on the culmination day, they were in court. When our lawyer pointed out that the event was over, they insisted they still had more arguments to make (laughs)!

Was there any official support from the community organisations like SNDP and NSS?

By the time they officially found out about it and could offer support, the event was over (laughs)!

Was the Sangh Parivar involved in organising the Mahamagham?

No. It was led primarily by the Juna Akhada and Mata Amritanandamayi Math. Several other sanyasis and gurus also joined us.

We heard you mention intelligence reports on some threats…

Not this time. But when I arrived here after the Prayagraj Kumbh Mela, some officers showed me a file containing various WhatsApp chats… there were threats from certain anti-national elements. Groups like Jamaat-e-Islami have their own agendas. Organisations like the SDPI have their own extremist nature. They will likely continue to express those tendencies. Now there seems to be a trend where the Muslim League is also swaying to extremist ideas. If you look at history, you will note that these extremist groups use everyone for their ends. From what I understand, even the CPM has been infiltrated by extremist elements.

Some socio-political observers termed the Mahamagham’s success as a sign of ‘Hindu awakening’...

Yes, it was indeed an event of Hindu awakening — an awakening of dharma. Sanatana Dharma refers to the eternal order — the alignment of human life with nature’s laws. Unrest follows when humanity moves away from that order.

At the festival, there was visible participation from folk traditions, tribal communities… Some observers viewed it as a political attempt to symbolically bring communities ranging from “Nayaadi to Namboothiri” together...

Historically, gatherings like Mahamagham or the Kumbh Mela brought together diverse sects and traditions. We tried to revive that spirit. The rigid caste divisions we speak of today are, in my understanding, later developments that hardened after invasions, changes in demography, and administrative restructuring.

But there were practices such as keeping away from the lower castes’ vicinity or preventing them from using the paths taken by upper castes...

What you now call ‘ayitham’ (untouchability) is an issue that emerged later. Earlier, communities confined themselves to their own spaces. They hardly went out. When they did, they were careful about unfamiliar environments and interactions. It was not originally about high and low, but about familiarity, discipline, and personal hygiene. Like what we saw during the pandemic. Even today, if you visit some Kurichyar or Muthuvan homes, you may not be allowed inside, and you may be served food outside. These communities are categorised today as ST.

So the idea of high and low, as it is viewed now, did not exist in that way earlier. Each community followed its own disciplines regarding coexistence. Only when population increased and communities began mixing more did this begin to be interpreted as untouchability. Later, according to my understanding, it was politicised and portrayed as caste malice by invaders. Over time, when power and wealth concentrated in certain hands, the system got corrupted. But even in that degenerative phase, you must note, Bharatiya culture did not have slave trade like what existed in Europe or Arabia.

Some rituals at Mahamagham — like the sacrifice of hens and cocks — were criticised as barbaric. How do you respond?

Such practices belong to ancient traditions of communities that lived in close contact with nature. In some lineages, animal sacrifice is part of ‘Veeraradhana’ or worship of valour. You point to the sacrifice of one hen or cock. Across the state, there are numerous slaughterhouses where animals are butchered daily. If society does not question that large-scale killing, singling out these ritual sacrifices seems morally dubious.

There were also concerns over river pollution as well…

Central and state agencies tested the river water on a daily basis. There were no issues. A few thousand people taking a dip in the river does not harm it. What actually affects the river’s health is the massive dumping of chemical waste, slaughterhouse waste, etc. These are the things that need to be corrected. But some people suddenly feel anxious when a Hindu ritual takes place. Let them sit there and whine.

Looking at it from an environmental perspective, the Bharathapuzha used to be a perennial river. Today, it’s dried up portions are a heartbreaking sight…

We are focusing on the rejuvenation of the Bharathapuzha, its ecosystem, and the culture associated with it. An expert committee has been studying this and we will prepare a comprehensive project. We hope to see positive results within the 12-year period starting from the 2028 Mahamagham.

Currently, we are seeing the rise of the ‘political Hindu’, rather than a spiritually enriched one? Won’t this only fuel intolerance?

A person living in society cannot escape ‘rajanaitikata’ — the system and ethics of governance and politics. Politics has always been intertwined with Dharma. Its expression varies according to time and place. Hindu thought promotes universal acceptance and intellectual freedom. However, when other organised religions function in expansionist ways, friction can arise. People instinctively defend their identity and existence when they perceive a threat. That said, consider the Parsis. Hindus historically had no conflict with Parsis. Friction arises when there is an attempt to usurp power or suppress others.

Recently, an ascetic in Kerala was seen exhorting Hindus to stand up against the alleged ‘Cutting South’ agenda…

Shouldn’t separatism be resisted? Calls for Hindus to unite against separatists should be viewed only as a response to threats to national integrity, not as attacks on other religions. Let other communities also articulate their commitment to national integrity in their own ways.

There have been discussions in Kerala about Hindu–Christian unity. What is your opinion?

When communities face common challenges, they may come together for mutual protection. Problems arise when religion seeks to directly wield political power. In Hindu tradition, seers and gurus critique society and correct distortions. Dharma has an internal corrective mechanism. In other religions, power structures can limit internal reform. That said, Christianity has evolved significantly since the medieval period. When communities adopt openness and coexistence, conflicts diminish.

Juna Akhada has a martial tradition. How is that relevant today?

There are 13 Akhadas in India, and the number of ascetics across them is said to be around 60 lakh — larger than our Army’s strength. Through spiritual discipline and physical training, monks cultivate inner strength and endurance. In ascetic philosophy, fire symbolises internalised knowledge, and ash represents transformation. Ascetics are expected to be capable of defending Dharma if required.

Rightly so, an article in the Organiser magazine describes you as a “warrior sage”. You were once a staunch leftist and atheist. How did that transition happen?

I was an atheist from Class 5. There was no sudden turning point. After college, I worked as a journalist. My travels to spiritual events and ashrams gradually transformed me. I realised the Leftist ideology was negative, confrontational, destructive. Recently, at an alumni meeting at Kerala Varma College, where I studied, I saw a 70-year-old alumnus still singing revolutionary slogans with words like “chorapuzha ozhukatte… (let a stream of blood flow)”. One can understand a youth shouting these lines, but at that age… Such a mindset remains trapped in negativity.

Did you hold any position in SFI?

Yes. I was the Thrissur district vice-president.

We have heard that your first trip to Prayag Kumbh Mela was to avoid police arrest. Is that true?

Yes. It was a period of student agitation. Multiple cases were filed against leaders. Some police officers advised me to stay away for some time. So I travelled to the Kumbh Mela after reading a small news item about it. I had no arrangements for food or stay. But food was freely distributed. I stayed for nearly a week. I attended several discourses but could not fully fathom them at the time. Still, the scale and spirit of the gathering left a deep impression on me.

When did you experience what one would call spiritual awakening?

Gradually, during my subsequent trips. I became a seeker, started roving with gurus there.

Communism speaks of liberty, equality and fraternity. Ancient Indian philosophy also speaks of oneness. Don’t they converge somewhere?

Communism, in my view, has characteristics similar to Semitic traditions in its structural rigidity. It seeks transformation through destruction. Bharatiya philosophy seeks transformation through sustenance and integration. There is a difference between cutting a knot and untying it.

Well, not all communists have read or adhere to ‘Communist Manifesto’…

(Laughs) That you need to ask them. I have read both the ‘Manifesto’ and ‘Das Kapital’. By the way, they still keep Stalin’s picture in the party office, right? The ‘deity’ is Stalin (laughs)...

There were reports that there is a blueprint to strengthen Hindu cultural centres in Kerala, especially Kalady, the birthplace of Adi Shankaracharya, who is said to have laid down the foundation for the Akhadas…

Take the example of Bharathapuzha. Along its banks lie numerous cultural centres that represent Kerala’s intellectual and spiritual heritage. But many of these institutions are not sustained with the respect they deserve. When there is community awakening, people naturally seek to strengthen the roots. Those who revere Shankaracharya will naturally feel his janmabhoomi should be preserved and celebrated in its full sanctity. Many groups, including the Juna Akhada, have plans. When the time is right, such collective aspirations may take shape.

There are ongoing controversies regarding temple administration in Kerala. Some propose bringing temples under independent trusts rather than government control. What is your view?

Isn’t it ironic that in a democracy, where citizens get to elect governments, devotees cannot elect those who administer their temples? As I said earlier, the Hindu tradition respects even atheists. But if someone, say a minister, comes before the shrine, they must respect the decorum. Otherwise, don’t go there at all. No one will complain. But going there and disrespecting sanctity is being intentionally offensive.

What is your opinion about non-Brahmin priests being appointed in temples?

In some temples, certain families may have hereditary rights. Some temples may have originally been family temples before coming under Devaswom control. In such cases, conflicts over rights can arise. In general, the central factor is not caste, but whether the person has studied the required Vedic traditions and follows the discipline expected.

The Juna Akhada is an ancient order of monks, over 2,000 years old. Yet, it was only last year that a Mahamandaleshwar was chosen with focus on Kerala. Why was this choice made now?

Historical records show that Akhadas did exist in south India long ago. However, because of constant Mughal and British invasions in the north, monks stationed themselves in conflict zones to defend the faith. South India didn’t face such prolonged, armed threats to Dharma. Incidents like the invasions of Hyder Ali or Tipu were relatively short-lived. This is why the Akhadas

TNIE team: Manoj Viswanathan, S Neeraj Krishna, Aparna Nair, Gopika Varrier, Lakshmi Athira, A Sanesh (Photos) Harikrishna B, Pranav V P (video)