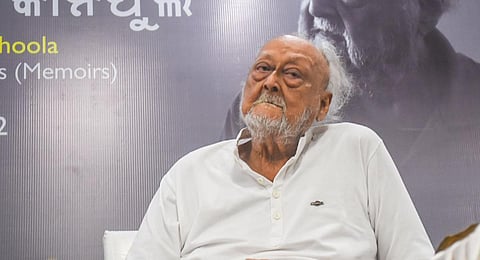

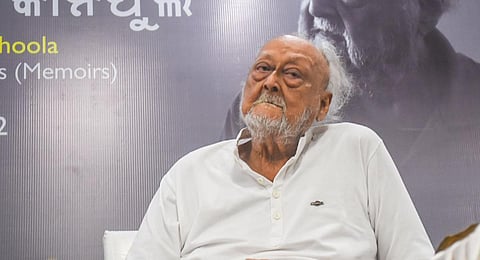

I have had the privilege of knowing Jayanta Mahapatra for several decades. I first met him when I joined Ravenshaw College for my intermediate in science in 1953. Perhaps, I attended a couple of lectures on electricity by him as a professor of physics. He had a long career in teaching, almost entirely in Ravenshaw College. I started knowing him properly from 1960s onwards. I have read all his poems.

He was born at Tinikonia Bagicha in Cuttack and his house had become a place of pilgrimage for writers - both from Odisha and outside. Over the years, I went to his house very often and enjoyed his company, talking about poetry in general and Odisha - its past and present - in particular. He too was very fond of me, gave me his books including ‘Relationships’ which won him the Central Sahitya Akademi award. It was a long poem, written in 12 movements. I still remember he gave me a signed copy of the book on July 26,1981, the same year he got the Sahitya Akademi award.

Jayanta Mahapatra started writing poetry fairly late in life. He began writing at around the age of 37 or 38. He started writing in Odia even later and published several anthologies which are highly regarded by fellow poets in Odia and the critics. He himself had eloquently explained the background to his writing poetry in Odia.

In his own words, “I suddenly discovered that all my supposed eloquence in English poetry had me drifting away from my own people. I was an outsider because I wrote in English, not Odia. I made up my mind and earnestly began writing my poems in Odia.”

This decision to be a bilingual poet was warmly welcomed by the writing community, particularly poets in Odisha. They found in his poetry a new voice which was earthy, structured more intimately on his Odia experience including Cuttack, the city where he lived his entire life. What they liked in his Odia poetry is precisely what he himself said about it: “I used simple, colloquial words because my vocabulary in Odia is severely limited. But I spoke with literal nakedness. These poems did not have the sophistication of my English ones. They were different, complementary. Maybe these were poems which revealed the naked truth in naked language, stripped of all exaggerated aestheticism. I can’t say. But my writing in Odia was a blow in self defence. I had dropped my masks.”

While I agree with his general observation regarding his own poetry in Odia, I sometimes wonder why he spoke of dropping masks for I am convinced that he is a man who never wore any masks. There have been many critical works on his poetry both in India and abroad looking at the basic inspirations behind his poetry, its simple and varied architecture and enviable sophistication which is never removed from his Indian and, more particularly the Odia experience.

Speaking of poetry, he had said, “A poem, therefore, appears to me to be full or made up of various times, may be like a dim corner in a room.” One of his telling statements about himself is in his essay ‘Time in the Poem’. It says so much about him as a person. The Odisha experience recurs in several of his poems. He had told me and I quote, “Odisha is in which my roots lie and lies my past and in which lies my beginning and my end.”

The universal element of his poetry is deeply anchored in the particular experience of his own state, its history and its contemporariness in existence. There are poems on Dhauli, Dawn at Puri, The Abandoned British Cemetery at Balasore and Shaped by the Daya. He translated into English several Odia poets. He had translated a bunch of my poems too. In fact, his own book ‘Waiting’ and his translation of my book ‘The Song of Kubja and Other Poems’ were released around the same time. That was his affection for me. During the translation, it was often that I was in his home.

In fact, I and my wife were family friends to Sir Mahapatra and his loving wife Runu. Both of us had become aware about how much Runu Apa inspired him to write poetry and its bitter-sweet impact on life. During the last part of his life, he was living alone. I had once asked him if he was feeling lonely. But as he told me, poets can never be lonely. “Because, they inherit the world; they draw the world into them. So how can they be lonely,” he said. I entirely agreed with him. Because, that also happened to be my philosophy that I have taken the whole world into my stride. Like him, poetry, I believe, is the tale of intimate relationships with things, persons, objects and everything else.

For poets like Jayanta and me, the past is always present. The future only peeps but the present and the past are summing up about 90 per cent of our lives. This is what Sir Mahapatra had told me. I think he was, in my estimation, one of the major poets of India. His poetry was unmatched and will remain so.

(As told to Diana Sahu)