Was Tamil Nadu Raj Bhavan's legal opinion on Governor's direct meetings with officials right?

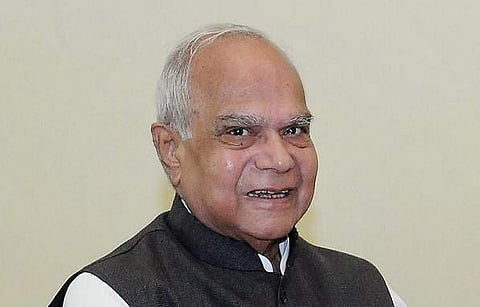

CHENNAI: Yet another week has gone by with the Governor Banwarilal Purohit at the centre of controversy. In an unprecedented move, the Raj Bhavan released a couple few statements and a legal opinion last week justifying the Governor’s regular, direct meetings with State government officials.

The opposition DMK sees red over the Raj Bhavan’s averments on the powers of Governors and has made futile attempts to initiate a debate on the matter in the State Assembly. The opposition fears that the Governor, being an appointee of the Central government, would encroach on the domain of the State government, if he were allowed to meet state government officials directly.

The legal opinion released by the Raj Bhavan makes sweeping conclusions on the powers of the Governor. “Whatever the executive can do, the Governor can also do. The executive powers of the state are vested in him. Same powers available to the State which are available to the Governor,” reads one of the far-reaching conclusions outlined in the six-pg legal opinion.

The opinion was given by Shreehari Aney, the former advocate general of Maharashtra, to the Governor Banwarilal Purohit last November. In short, the opinion, which Raj Bhavan believes is the “correct legal position”, appears to virtually equate powers of the Governor with those of the Chief Minister, if not over his. In response to the Raj Bhavan’s statements, the DMK working president MK Stalin has asked the Governor to go through various Supreme Court judgments dealing with the powers and role of the Governor.

So, who is right? The Constitution, the supreme law of the land, has dedicated some Articles exclusively to the Governor, his role and powers. A plain reading of Article 154 of the Constitution suggests that Aney may be right in his opinion.

“The executive power of the State shall be vested in the Governor and shall be exercised by him either directly or through officers subordinate to him...” the article reads. The words used in Article 164, too, give an impression that it is the Governor who is the ultimate authority in the State government. For example, Article 164 says that a minister hold office at the “pleasure of the Governor.”

But the law is not merely a plain reading of words in select sections, but a holistic understanding of the essence any statute. One has to go through the Preamble, various Articles of the Constitution and the interpretations provided by the Supreme Court over decades to know exactly what the Constitution intends to mean.

The doubts over the powers of the President and Governors were fresh in the early years of Independence. But in 1955, a four-member bench of the Supreme Court, in a case against the Punjab state government, made things emphatically clear. The court said the Indian Constitution had adopted the British system of the parliamentary form of government.

“The president has thus been made a formal or constitutional head of the executive and the real executive powers are vested in the Ministers or the Cabinet. The same provisions obtain in regard to the Government of States; the Governor or the Rajpramukh, as the case may be, occupies the position of the head of the executive in the State but it is virtually the council of Ministers in each State that carries on the executive Government,” the order dated April 12, 1955 and penned by Justice Mukherjea said.

Nineteen years later, a nine-member bench of the Supreme Court, led by then Chief Justice A Ray, further succinctly put it as, “The Governor means, the Governor aided and advised by the Ministers,” in the order dated August 23, 1974.

The court further clarified that the office of the Governor is not the fountainhead from where the powers flows or where the ultimate responsibility of the State’s administration lies. “Although the executive power of the State is vested in the Governor actually it is carried on by Ministers...” the court said, when rejecting arguments that an order passed by the then Punjab Chief Minister was invalid because it did not have the approval of the Governor.

So was Aney right in his conclusion that “whatever the executive can do, the Governor can also do”? Aney did not quote any Supreme Court interpretations to substantiate his conclusion. But

these two Supreme Court verdicts quite clearly show that the Constitution does not really mean “Governor”, when it says Governor, but only means “Council of Ministers”, whose head is the Chief Minister.

Even otherwise, can governor act on his own, without the advice of the Council of Ministers? Aney says, in his legal opinion, that Purohit had written to the Chief Secretary and the Revenue Secretary to arrange for his meetings with the district-level government officials and that this falls under “executive powers” of the State. So, was the Governor correct in taking up such independent action, when he was not advised by the Chief Minister to have such meetings? A similar question was raised before the Supreme Court in 1950 on whether the Governor could exercise his executive powers independently.

It was argued that since the provisions relating to Governors were similar to provisions in the colonial Government of India Act (when the Britain-appointed governors enjoyed immense power over the elected government), the State Governors now also enjoyed same powers. But the Supreme Court ruled, “The Governor under the present Constitution cannot act except in accordance with advice of his Ministers. Under the Government of India Act, 1935, the position was different… Under the present Constitution, the power to act in his discretion or in his individual capacity has been taken away and the Governor, therefore, must act on the advice of his Minister..”

The Governor can act in his discretion only in matters in which he is expressly required by or under the Constitution. Some of these areas include inviting a Chief Minister to form a government and referring a State Assembly’s Bill to the President, if the Bill may go contrary to laws enacted by the union government.

So, all key Supreme Court judgments say that a Governor is just a titular head of the State in whose name the Council of Ministers, headed by the Chief Minister, runs the administration and the ministers are responsible only to the State Assembly. The Governor can do little, without the “aid and advice” of the ministers.

Another one of Aney’s far-reaching conclusions is that such “aid and advice” of the ministers are just a “pre-condition” to a Governor’s action. And if a minister, as in the instant case of Governor Purohit meeting officials, was aware and later declares that he had no objections to the Governor’s actions, the post-gratification was enough to make them legal.

If the minister later declares there is “nothing wrong” in the Governor meeting officials, it amounts to “waiver of the pre-condition” for any similar future actions of the Governor. Aney did not elaborate on whether such a waiver by a minister would apply only to conducting meetings or exercising any of the other powers of the State’s executive.

In other words, it means that a minister could relegate (or disown) at least some of his powers as an elected representative to the Governor by making such open declarations. Again, Aney did not refer to any Supreme Court rulings to substantiate his conclusion.

The country has not witnessed such a situation in the 70 years since Independence, and hence none of the courts have dealt such a scenario. But a 1974 ruling by the nine-member Supreme Court bench could hold answers to this.

“It is a fundamental principle of English Constitutional law that Ministers must accept responsibility for every executive act. In England, the sovereign (equivalent to President and Governor) never acts on his own responsibility… The Indian Constitution envisages a parliamentary and responsible form of Government at the Centre and in the States and not a Presidential form of Government. The powers of the Governor as the Constitutional head are not different,” the ruling said.

Aney also says that it is the duty of the Governor to be acquainted with the true state of affairs of the “territory he governs” and hence he is right in holding direct meetings with State government officials. In another place, Aney says the actions of the Governor become illegal only if he had issued directions directly to the officials, "without approaching the concerned minister." This implies that the Governor has powers to take an independent decision and instruct a minister.

The Clause 2 of the Article 164 says, “The Council of Ministers shall be collectively responsible to the Legislative Assembly of the State.” The Constitution itself says clearly that the minister's

responsibility lies only towards the State Assembly, not the Governor.

The Raj Bhavan's statements further say that the Governor's meetings are necessary for him to send "meaningful monthly reports" to the President. None of the Articles in the Constitution speak of such monthly reports that a Governor need send. None of the prominent books on Constitutional law speak of such reports either.

So, was Governor Purohit right in conducting regular meetings with government officials?

The Constitution and its interpretation by the Supreme Court make it clear that he neither “governs a territory”, nor can exercise any executive powers. His meetings are, at the very least, not required, if not illegal under the Constitution.

The Constitution does provide for some additional discretionary powers to the Governor when compared to that of the President. The discretionary powers are not defined in the Constitution but have been deducted from the tone and tenor of the Constitution over the years.

Some of these discretionary powers are:

1. A Governor, when holding the office as Chancellor of a University, need not act as per the advice of the Council of Ministers.

2. Governor can independently decide whether a Chief Minister can be prosecuted in any criminal case. But in case of other ministers, he may have to rely on the advice of the Chief Minister.

3. Reserving assent to any of the bills passed by the State Assembly or referring any of the such bills to President for the Union Government’s review. This applies mostly when the State’s legislature goes against Constitution or Central government’s laws.

4. Sending report to the President under Article 356 if there is a breakdown of the Constitutional machinery in the State and recommending implementation of President’s rule.

5. Appointment of the Chief Minister based on his assessment of who is likely to command the confidence of the State Assembly.

Some of the key recommendations made on reforming the office of Governor:

1. The Sarkaria Commission, set up in 1983 on Centre-State relations, had strongly recommended against the appointment of “discarded or defeated politicians” as Governors to avoid suspicion on whether they were acting with a political interest.

2. Administrative Reforms Commission suggested in 1969 that some guidelines should be evolved on discretionary powers of the governors to maintain uniformity of actions. But Centre did not accept the suggestions and said the best course would be to allow conventions to grow up.

3. Committee of Governors set up in 1971 study the ‘Role of Governors’ said that instances of governors acting on their own discretion must be extremely rare.