In 1577, nearly one-and-a-half centuries after the invention of the movable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg, Tamil became the first non-Roman language to get printed. Doctrina Christam (Tambiran Vanakkam), a Catholic catechism translated from Portuguese to Tamil, was the first work to be printed, either in Goa or Cochin.

It took another one-and-a-half centuries for a printing press to be set up in present-day Tamil Nadu. In 1712, the missionary Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg set up a press in Tranquebar, which was at the time a Danish settlement. Two years later, the same press published the full Tamil translation of the New Testament, the first in any South Asian language.

While publishing in Tamil remained tied to missionaries and later to the East India Company’s seat of power, Fort St George, the abolishment of licencing of printing press by Governor General Charles Metcalfe in 1835 paved the way for printing technology to proliferate across the Tamil-speaking geography.

The later half of the 19th century was a momentous period in Tamil history with numerous ancient texts found on palm-leaf slats coming out in print, primarily owing to the monumental efforts of personalities such as U Ve Swaminatha Iyer. These texts would throw new light on Tamil culture and history.

Interestingly, not only ancient texts but also the printing of contemporary Tamil literature during the period was sustained solely by the patronage of religious mutts and rulers of various kingdoms and provinces. However, due to social transformation spurred by colonialism, the social classes that indulged in such patronage saw a decline, which consequently led to a lull in the publication of contemporary literary works in Tamil.

To tackle this decline in patronage, Tamil scholars turned to a subscription model, whereby an upcoming literary work would be advertised, appealing to the newly educated elites to subscribe to the work. One of the earliest instances of such an appeal was made by C W Damodaram Pillai, who published a number of classical Tamil texts.

“To ensure that people who involve themselves in such (publishing) projects don’t lose money, all those who have passed university examinations and are well-placed in high jobs ought to buy a copy each of all the classics published in their mother tongue,” he said.

The response to such appeals were encouraging, but were not sufficient for the Tamil publishing world to thrive. The poet Subramania Bharathi, who emerged on the scene in the early 20th century, was also among those Tamil literary figures who had struggled to get their work published.

As it happened, Tamil publishing became profitable with the arrival of novels in a big way during the second and third decades of the 20th century. Novels of varying quality got published in huge numbers at the time, with almost every Tamil periodical carrying novels in serialised form. Moreover, until then, authors had largely undertaken the responsibility of publishing their own work and selling them; this period saw a paradigm shift, with the emergence of publishers and publishing houses.

It was also when modern Tamil literature began to take shape, with the publication of magazines such as Manikkodi, which went on to spark a literary movement that resulted in the arrival of a whole new breed of writers, including Pudhumaipithan and C S Chellappa.

Today, the Tamil literary scene is not only thriving within the Tamil-speaking realm, but has also grown outside of it, among readers of other languages, especially English, mainly through translations. More recently, the overwhelmingly positive critical reception gained by the English translations of author Perumal Murugan’s works has opened up a huge avenue for translated works from Tamil. Pyre, the translation of Perumal Murugan’s Pookuzhi, placed in the longlist of the International Booker Prize last year.

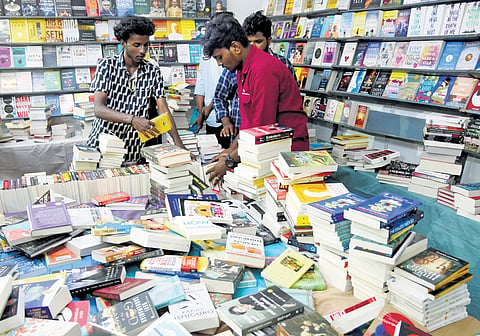

Moreover, the Tamil Nadu government’s recent efforts to translate important Tamil works into English has provided a further boost for these works to reach a wider audience, from around the globe. The annual Chennai International Book Fair has also shaped up to be a solid platform for Tamil texts to reach not only English readers, but also readers of numerous other languages such as Polish, Norwegian, Arabic, Italian, Spanish, and French.

The birth of modern Tamil literature

Tamil publishing became profitable with the arrival of novels in a big way during the second and third decades of the 20th century. Novels of varying quality got published in huge numbers at the time, with almost every Tamil periodical carrying novels in serialised form. It was also when modern Tamil literature began to take shape, with the publication of magazines such as Manikkodi, which went on to spark a literary movement that resulted in the arrival of a whole new breed of writers, including Pudhumaipithan and CS Chellappa.

(Historian AR Venkatachalapathy's The Province of the Book served as the key reference for this article.)