VELLORE: Mohini*, a noon-meal cook at a government school in northern Tamil Nadu, is hunched over a steel basin, peeling the shells off freshly boiled eggs — lunch is barely half an hour away. She dips each egg into a bowl of water before transferring it into a vessel. Her assistant, Ramani*, helps her finish the task. The eggs peel easily today, but Mohini’s mind is elsewhere — on the long afternoon that awaits her, once the school shift ends.

Since the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) began on November 4, her life has followed a punishing rhythm, as Mohini is not just a cook; she is also a Booth Level Officer (BLO) in charge of SIR duty.

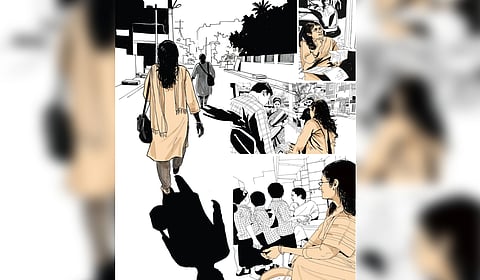

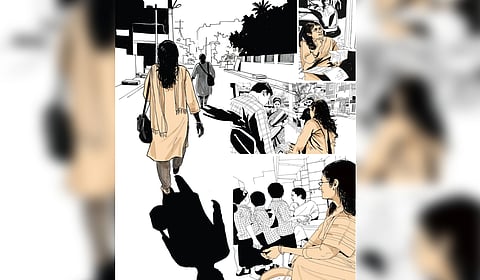

While other BLOs zip through their routes on two-wheelers, Mohini, who is in her forties, moves at a slower, steadier pace - on foot, house after house, lane after lane. Juggling between jobs, she clocks nearly 4-5km daily, driven by a spirit that refuses to tire even when her legs do.

Her day begins at 5 am. She wakes, bathes, cleans the house and prepares breakfast and lunch for her college-going children. After quickly gobbling up a dosa or idli, she rushes to the school. Until early November, this routine felt manageable. But with the added SIR workload, she barely gets a moment to sit. By 9.30 am, she must be inside the school kitchen.

Her morning follows the same sequence: chopping vegetables, cooking rice, preparing a large vessel of sambar, then settling down to peel eggs. Before the food is served to the kids, Mohini, Ramani and their supervisor eat the food to ensure that the seasoning is right.

As she eats, her phone buzzes constantly — voters calling to clarify doubts, asking her to visit their homes, and election officials checking whether she has begun her rounds. At times, voters call as late as 10 pm, asking if they could collect the forms then, or to clarify doubts.

At 12.30 pm, Mohini and Ramani carry the heavy pots of rice, sambar, and eggs to the school building. Ten minutes later, the lunch bell rings, and they serve food to nearly 180 children before returning to wash the vessels and clean the kitchen.

Only after locking up can Mohini leave. Around 1.45 pm, she begins the 2-km walk from the school to her home — just to prepare sambar for the evening — something she does in advance so that, after returning home, she can quickly make dosas for dinner. After that, she walks back another kilometre to board bus to her assigned SIR area, 2km away.

Carrying out her entire fieldwork on foot, Mohini goes from house to house, covering the 850 voters assigned to her. Parked two-wheelers and compound walls become her makeshift tables where she spreads out forms, checks lists, and makes entries. So far, she has submitted back almost 80% of the SIR forms.

Pointing to a house where a resident casually tells her to return in two days, she said, “This is the sixth time I’m coming here. They’re educated people. If they don’t cooperate, what will I do?” At the next house, a dog charged from behind the gate as she knocked. “The lady here is always sleeping when I come,” she muttered.

During her 4-6 hours of walking, Mohini does not drink water. “If I drink water, I’ll need a toilet. Residents might hesitate to let me use theirs,” she said. With barely a few spoonfuls of rice and no water, she pushes on, her steps steady though her fatigue is visible.

Meanwhile, a voter calls out from her doorstep, “My son was waiting for you. You never came — we didn’t have your number.” There is no phone number in the form, she argued, only to fall silent when Mohini showed her name and number clearly printed on the top of the form.

Amidst all this, her phone rings 30 to 40 times — calls from her supervisor, voters, and her daughters. When her younger daughter calls, Mohini listens with half a mind, scanning her voter list simultaneously. She feels guilty, but the pressure to finish her work doesn’t allow her even 10 minutes of stillness.

At every junction she stops, a group of voters approaches with queries. Mohini gathers whatever details (from 2002) the voters know and assists them. However, unlike many BLOs, she doesn’t have to trace SIR 2002 details and digitise the forms.

A team at the Vellore collectorate pulls up the old data once she submits the forms to cross check and fill out the missing details. At some booths, corporation or revenue staff have been tasked with uploading the forms online, which usually takes 1-3 minutes. However, the task becomes annoying when the app crashes and it takes 20 minutes to upload a single form.

As dusk falls, she sits near a tea stall, brushing off mosquitoes while counting forms. With the ECI’s December 4 deadline (now extended to December 11) nearing, her supervisor has asked for all forms to be submitted immediately.

The tahsildar will arrive in a bit to collect them from the team. However, Mohini insists on rechecking locked houses the next day, as she doesn’t want even a single voter wrongly removed.

Some homes have remained locked despite multiple visits. Sometimes neighbours help trace residents; in other cases, even they don’t know. “Some people haven’t given phone numbers. How do we find them,” she asks. When every attempt fails, she marks the form as “DL”— door locked.

By 8 pm, Mohini is finally done for the day. She places the remaining forms into her bag and begins the 1.5-km walk to the bus stop. The road is dim, but she barely notices. The past month has worn her down. “With all the walking, my back keeps hurting. There’s no time to eat properly or rest,” she says.

(*names have been changed to protect identities)