For a country as vast and layered as India, a single, monolithic “Indian design” is an impossibility – and perhaps even an injustice. The strength of this civilisation has always been its plurality: of languages, landscapes, rituals, food, crafts and ways of imagining the world. If design is, at its core, the way a culture thinks through form, function and meaning, then our design story must also honour this diversity.

In that sense, a mature national design narrative for India will not come from flattening everything into one visual shorthand, but from recognising and articulating strong regional design identities, each with its own history, logic and contribution to the present.

Among these, Tamil Nadu and the broader Dravidian region stand out as a design civilisation hiding in plain sight. Yet, in Indian design schools, in industry presentations and in everyday conversations, the names that roll off our tongues are often Scandinavian chairs, German appliances, Italian cars or Japanese minimalism. We casually praise “Nordic clarity”, “German engineering” or “Italian styling”. There is nothing wrong in learning from these traditions. The problem is that we have internalised a colonial hierarchy of taste, where European or East Asian design identities are aspirational, while our own remain either folklorised or ignored.

This blind spot is particularly striking when we look at what archaeology and history have been telling us.

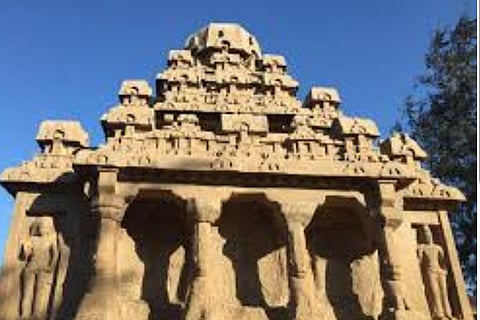

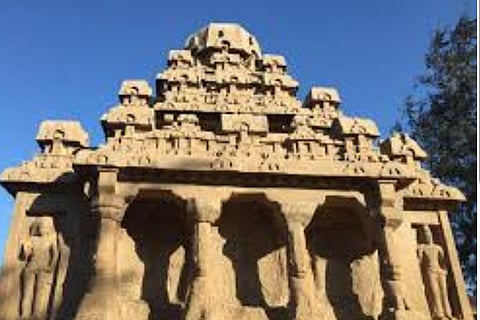

The Keezhadi excavations in Sivaganga have pushed back the timeline of urban sophistication in Tamil Nadu to around 2,600 years. What is emerging there is not merely “old pottery”, but evidence of a design culture: industrial processes in weaving, dyeing, bead-making and metallurgy; systematic layouts of settlements; water management and waste systems that show an integrated understanding of environment and community. Add to this the architectural precision of Dravidian temples, the durability of the Kallanai dam – still functional after nearly two millennia – and the craftsmanship of Chola bronzes, and a pattern becomes hard to ignore.

Long before we borrowed the language of “human-centred design” or “sustainability”, the Dravidian region had already been practising versions of both, anchored in context, climate and community. If this is the case, why does “Indian design” in popular imagination so often get reduced to something else entirely – a kind of hurried visual mash-up: bright colours, paisley, elephants, kitsch typography, Bollywood nostalgia? There is a growing global appetite for this aesthetic, but it risks trapping India in a surface-level identity: loud, playful, decorative – and often detached from the deeper design intelligence of its regions. This is where Dravidian design becomes a necessary corrective.

The argument is not about replacing one stereotype with another, but about shifting the conversation from decorative cliches to systems, values and lived intelligence. Dravidian design is not merely a motif or colour palette; it is a way of thinking that history keeps demonstrating – in how temples organise movement and community life, how tanks and dams negotiate water, how crafts optimise material, and how contemporary enterprises build resilient ecosystems.

To move beyond “Indian kitsch” as our default export identity, we need to research, articulate and celebrate Dravidian design as a serious domain. The “why now?” becomes clearer when we situate this in the last 200 years of Tamil Nadu’s trajectory.

The design story did not stop with temples and dams. It continued in factory floors, engineering classrooms, coding bootcamps, government health care systems and neighbourhood grocery stores. The missing piece is a coherent, named identity that connects these dots in the global mind. Just as K-Pop, K-beauty and K-drama turned Korean cultural practices into recognisable global tags, or anime and manga did for Japan, Dravidian design could become a powerful anchor for how the world encounters Tamil Nadu and, by extension, India.

If Dravidian Design is to move from concept to policy and practice, the state needs a clear five-year roadmap. For a state that has quietly influenced how India travels, learns, consumes and now codes, claiming Dravidian design is not an act of regional vanity. It is an act of intellectual honesty – and a strategic move to ensure that, in the next century of global narratives, Tamil Nadu’s design genius is not just exhibited in museums or hidden in patents, but recognised, named and consciously evolved as a living identity.

(The author is vice president of Strategy at the DOT School of Design)

Footnote is a weekly column that discusses issues relating to Tamil Nadu