HYDERABAD: Widespread dieback of neem (Azadirachta indica) trees across Hyderabad and several districts of Telangana has prompted the Forest College and Research Institute (FCRI), Mulugu-Hyderabad, to initiate a comprehensive, multi-dimensional scientific investigation to understand the cause, impact and long-term implications of the phenomenon.

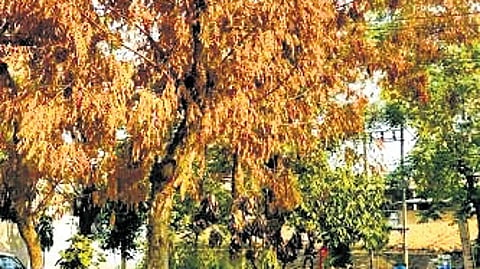

Over the past few years, neem trees - considered a vital ecological, medicinal and cultural symbol - have been exhibiting alarming symptoms, including drying of upper branches, thinning foliage, reduced flowering and fruiting and significant canopy loss. The visible deterioration has raised public concern, particularly in urban areas where neem trees play a crucial role in microclimate regulation and biodiversity support.

What Is neem dieback?

According to V Krishna, IFS, Dean of FCRI and Conservator of Forests (Research & Development Circle), neem dieback is characterised by the drying of top branches soon after the monsoon season. “The infection begins at the top branches and gradually progresses downward. In some cases, the entire canopy is affected, though in many trees it remains limited to the upper crown,” he explained.

Identified cause: Phomopsis azadirachtae

The disease becomes prominent immediately after the rains, as Telangana transitions into winter. “This is when the pathogen becomes active. From October to February, the drying is clearly visible. By March most neem trees begin to recover naturally,” Krishna told TNIE, emphasising that neem is a highly resilient native species.

FCRI’s investigations, first initiated in 2021 after observing large-scale twig blight and dieback on its campus, identified a fungal pathogen —Phomopsis azadirachtae — as the primary causative agent. Laboratory isolation of infected twigs, branches and collar tissues consistently revealed pycnidial and conidial structures characteristic of the Phomopsis genus.

The dean emphasised that while the pathogen was earlier reported mainly in northern India, it has now spread extensively across southern India, including Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and neighbouring regions.

Although neem trees typically recover after winter, the temporary damage has serious ecological consequences. Drying of top branches affects flowering and fruiting, leading to a sharp decline in seed production. Since neem seeds are primarily dispersed by birds, reduced fruiting has resulted in poor natural regeneration.

This directly threatens future neem populations,” Krishna said, adding “less seed dispersal means fewer young trees replacing older ones.” Importantly, FCRI clarified that neem dieback poses no threat to human health. “Neem continues to be safe for medicinal and traditional use. This disease affects only the tree, not humans,” Krishna stressed.

Earlier treatments and their limitations

To combat the disease, FCRI earlier developed a three-step integrated fungicide protocol involving Carbendazim (Day 0), Thiophanate-methyl (Day 7), and Profenofos (Day 20), targeting both the fungus and associated insect activity.

A pilot study conducted in 2023 on the FCRI campus showed visible recovery in treated trees, including new leaf flush and gradual canopy restoration.

However, Krishna acknowledged that similar remedial measures suggested by agricultural universities — such as trenching, water drenching, and fungicide sprays — did not yield consistent results in city conditions.

“In most cases, the tree recovered on its own with the arrival of summer, not necessarily because of treatment. By then, the damage had already occurred,” he said.

Need for in-depth research

Recognising these limitations, FCRI has now launched an extensive, long-term research programme under the guidance of Dr Jagadish, head of the Department of Forest Resource Management and a specialist in plant pathology. The study will focus on identifying why Phomopsis azadirachtae becomes highly active during specific seasons and how infections can be prevented rather than merely treated.

The research will cover the expanded GHMC area, examining stress factors such as water scarcity, air pollution, soil compaction, and climate variability. For comparison, samples will also be collected from remote, undisturbed regions to determine whether environmental stress plays a decisive role. “If rural and urban areas show similar infection levels, we can conclusively say this is not driven by pollution or climate change alone,” Krishna explained.

Focus on resilient trees and future solutions

Another critical component of the study involves identifying neem trees that remain unaffected despite widespread infection. “Nearly 80-90 per cent of neem trees show symptoms, but a few remain completely healthy. We want to understand why,” Krishna said. FCRI plans to study these resilient trees and develop protocols for producing disease-resistant seedlings through techniques such as tissue culture and micropropagation. These resilient varieties could form the backbone of future plantation and urban greening programmes.

A call for collective action

While stressing that neem dieback is a natural ecological process and not man-made, FCRI has called for coordinated action involving municipal bodies, forest and agriculture departments, educational institutions, NGOs, and citizens. Public cooperation in reporting severely affected trees and supporting scientific sampling will be crucial for the success of the study. “Neem is not just a tree-it is part of our cultural and ecological heritage,” Krishna said. “Protecting it is both a scientific responsibility and a cultural duty. With structured research and timely intervention, neem trees will not only recover but continue to thrive across Telangana and the country,” he added.