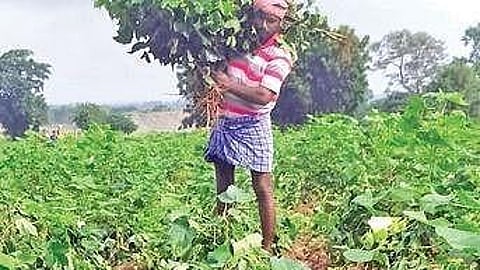

ADILABAD: For decades, the contentious issue of podu (shifting forest land) cultivation has remained unresolved in the erstwhile Adilabad district, despite repeated assurances from successive state and Union governments. A permanent solution continues to elude both forest officials and cultivators, even as political promises flare up around every election cycle.

Forest officials are yet to demarcate boundaries in several areas and are struggling to dig protective trenches due to continued occupation and opposition from cultivators. Ironically, it is the same ground-level forest staff, tasked with protecting these lands from encroachers and smugglers, who now find themselves issuing clearances for cultivation certificates, acting on political directives or government assurances.

Political parties, particularly the BRS and Congress, have made repeated promises to distribute pattas (land ownership rights) to those cultivating podu lands. Ahead of the Assembly elections in 2014, 2018 and 2023, both parties pledged patta distribution upon forming government, creating a moral and operational dilemma for field-level forest staff.

The previous BRS government under former chief minister K Chandrasekhar Rao did issue a limited number of pattas to cultivators. Earlier, in undivided Andhra Pradesh, then chief minister YS Rajasekhara Reddy had issued pattas to more than 30,000 forest land cultivators. These measures, while politically driven, have inadvertently encouraged further encroachment, as cultivators hope for eventual regularisation of their occupation.

‘Smuggling still the only source of income for many’

The degradation of forests continues unchecked in many areas, exacerbated by political backing and administrative ambiguity. A recent incident in Keshavapatnam village under Sirichelma forest range highlights the conflict. Villagers, allegedly incited by teakwood smugglers, obstructed a plantation drive, attacked forest staff and damaged police vehicles. One police personnel was injured in the assault.

Many residents of Keshavapatnam, particularly among the Multani community, reportedly depend on illegal teakwood trade for their livelihood. Forest and police teams have made several attempts to enter the village, but have faced stiff resistance. A government-appointed committee was formed to explore alternative livelihoods for the community, but it has yet to offer any tangible solution.

Forest officials estimate that around 1,600 acres have been degraded due to illegal podu cultivation and teakwood smuggling in this region. Following the recent attack, forest personnel submitted a memorandum to the district collector, demanding weapons for self-protection.

The most serious cases of forest encroachment continue to be reported from Kumurambheem Asifabad and Adilabad districts.