NEW DELHI: Pushpa, 55, works as a domestic worker in the national capital’s Pant Nagar area. She is sceptical how she would be able to continue earning her livelihood if she has to relocate to a resettlement area.

“We have been staying here for over two decades now. But there is a court order that the jhuggis would be demolished. We are likely to be resettled in far-off areas. We do not know how we will eke out our living once displaced,” said Pushpa.

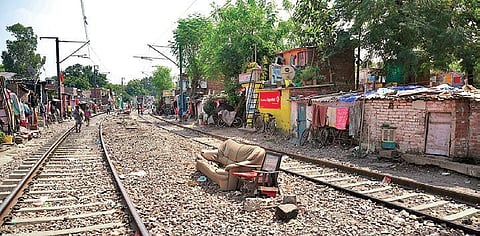

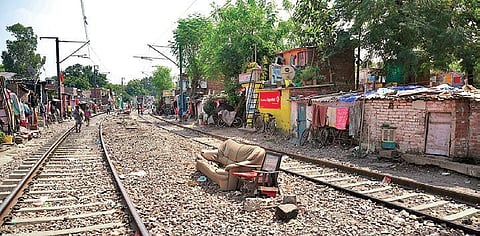

The issue of resettlement gains further significance in light of the recent Supreme Court order which directed the removal of 48,000 households in settlements on Railways land across Delhi.

This order specified households within the ‘safety zone’ should be removed in three months. The Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) data shows that 76 settlements are covering about 51,000 households on Railways land.

An analysis by Delhi Housing Rights Task Force (DHRTF) -- a collective of housing rights organisations, research institutions, activists and researchers -- said the total area settled by these households amounts to 0.006 per cent of Delhi’s total land area. The Economic Survey of Delhi 2018-19 showed that one-third of Delhi lived in sub-standard housing.

“As per the SC guideline, we have to relocate 48,000 families or around 3.5 lakh people within three months. We have appealed for a time frame of a year. We had requested the Railways and Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs to hold a joint meeting to figure out the way ahead and the Railways to share the relocation cost. We have not got any response from either. There is a need for a smooth transition...This cannot be carried out all of a sudden,” said Bipin Rai, DUSIB member.

Documented evidence from across the country reveals increased suffering and impoverishment, on account of poorly designed and inadequate resettlement sites, situated mostly on city margins, said Shivani Chaudhry, executive director, advocacy group Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN).

“Concerning the order for settlements on Railway land in Delhi, the government must ensure that no one is forced to move to vacant flats in remote sites, as that will lead to loss of livelihoods and education,” said Chaudhry.

When people reside in areas near railway lands, a significant number of people who rely on scavenging from tracks lose access to their source of income, pointed out Srinivasu Pragada from Andhra Pradesh-based Association for Urban and Tribal Development. The Economic Survey of Delhi 2018-19 said Delhi needs 24 lakh new housing units by 2021.

Of these, 54 per cent were required for the economically weaker section and lower-income group.

A 2014 HLRN study “Forced to the Fringes: Disasters of Resettlement’ in India” showed that governments of Delhi, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra had breached state, national, and international laws while resettling people. People in resettlement sites reported violations by government and implementing agencies of their basic human rights.

In-situ upgradation, where tenure security and services were provided but no new houses are built, remains the fastest, cheapest, and most effective way to ensure adequate and affordable housing, said a DHRTF analysis recently submitted to the DUSIB and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.

It can be explored if Railways can be given alternate equivalent land or development rights in other locations, the DHRTF recommended.