“On the 6th of September in 2018, I was no longer a criminal. And at that moment, it felt truly freeing. Then reality sank in,” says Saptarshi Bairagi, National Convener of the Indian Queers’ Collective and the nation’s first Dalit Queer anthropologist. “Since then, there’s been an ocean of negativity, but let me concentrate on the positives.”

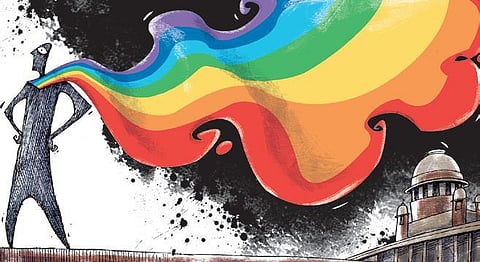

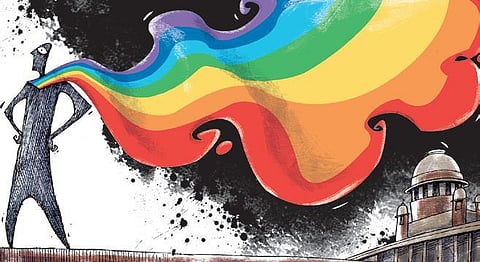

After the landmark decision of the Indian Supreme Court to revoke Section 377, which has its roots in “the act of buggery as an unnatural offence” dating back to the British Raj, India finally had a chance to be free. “It was the latest phase of decolonisation, something that is still prevalent across South Asia. While there are several more barriers to take down, like the recognition of same-sex marriages in the country, we hope this adds as a catalyst for other countries in the subcontinent and the greater South-East Asian region,” notes Bairagi.

Hotelier and fierce LGBTQ+ advocate Keshav Suri, who was among the five petitioners who challenged Section 377 says, “The reading down of Section 377 has been a significant but small step. The road to equality is a long one. In the last three years, there has been better understanding and acceptance for the community; however, we are yet to witness real change.

We need proper representation and jobs, beyond the pinkwashing. We need anti-discrimination law, marriage equality, and equity for non-cis identities to begin with.” Mentioning the marriage-equality movement, Suri adds, “When we talk about queer liberation, marriage equality is only one part of the larger scheme of things. Though I believe that marriage as a right should be available to everyone irrespective of their gender, caste, and sexuality, there are things like discrimination at work, bullying, and access to opportunities such as education and employment, which are bigger challenges that must be overcome.” Explaining this further, Suri adds, “Imagine a scenario when you marry but have no access or rights to things such as a joint bank account, insurance or visiting rights. A lot of people do not want to get into an institution like marriage, and that should be okay too.”

For Myna Mukherjee, who runs Engendered, a human rights collective especially passionate about the queer community, it is about the next generation. “We will keep doing our part, but it is hopeful to know that our efforts and the decriminalisation of that law has allowed younger generations, who are coming to terms with their identities, a space where they can talk how they feel and more without the pressure of penalisation.”

There are a few people younger than these social justice warriors who are carrying on the fight. Aarya Bhattacharyya, 24, who is pursuing her Masters in Psychology from Amity University, Noida, is conducting a study on ‘the stigma of homosexuality among young adults in India’. Bhattacharyya is all in. An exploring demi-sexual, she notes, “There is little discrimination when it comes to ‘alternate sexualities’ in the urban youth, whether they are from Delhi or Chennai. But the message hasn’t petered down yet to people coming from less urban as well as rural backgrounds. It’s not become a conversation that can be openly had for them.”

Bairagi agrees. They say, “That revocation was the first step, but we have a long way to go. This engagement needs to cross social, religious, caste, and communal barriers. We need to be an example for the rest of the South-East Asian community, so that no matter whether you’re in Pakistan or Nepal, you feel the same level of security that a heteronormative person does, anywhere.”

Delhi-based Pranav Kapoor, a perfumer who runs Indian Naturals, concludes, “It’s about the mindset. We could be having this conversation today or 10 years earlier. It’s not so much about laws as it is about attitudes, and that’s what needs to be worked on.”