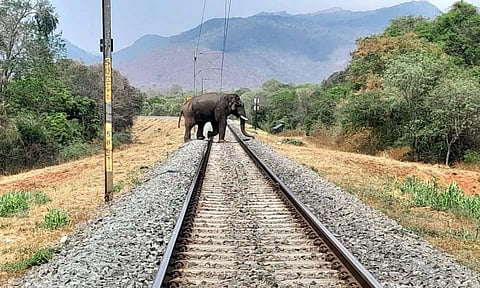

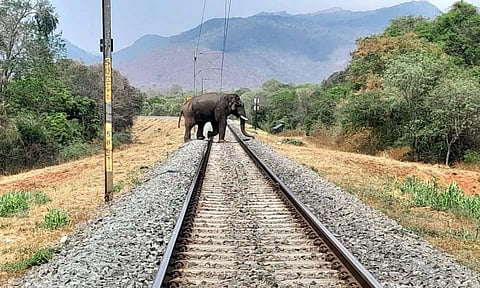

For several years in West Bengal, there was endless buck passing between the state government and the Indian Railways on how to stop the death of elephants on railway tracks running through the state’s dense forests.

Only in 2018 did the central government and a state agency finally decide to set up a joint committee to prevent such deaths, but not before the Rajya Sabha was informed that as many as 30 elephants died in Bengal after being hit by speeding trains between 2012-2017. The primary responsibility of the proposed committee was to coordinate and identify railway track zones that are transit points for elephants. Various railway lines in north and south Bengal cut across forest land and paths frequented by elephant herds.

Mind you, Bengal is by no means the principal culprit. Assam topped the list with 90 casualties, followed by Odisha with 73, Tamil Nadu with 68 and Karnataka with 65, while Kerala saw 24 elephants perishing in circumstances that were not natural. In some other states, the numbers were not big enough to be computed but added to the brutal, callous tally, nonetheless.

In fact, in December 2022, the Union environment ministry told the Lok Sabha that India has lost 494 elephants to train accidents, electrocution, poaching and poisoning over the past five years, highlighting the challenges undermining elephant conservation efforts. Of the 494, electrocution through contact with power transmission lines accounted for 348 elephant deaths followed by train accidents (80), poaching (41) and poisoning (25), between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

While tiger conservation has justifiably caught the imagination of the public for several years, thanks to the political push it has received at the highest level by successive dispensations, the safety of elephants -- revered in many parts of the country as the embodiment of Lord Ganesa -- has received relatively little attention.

Wildlife experts have been at pains to say that while 494 deaths over a five-year period appeared to be a fraction of India’s estimated population of nearly 30,000 wild elephants, such deaths could disrupt herd dynamics and enhance the risk of human-elephant conflicts. The overall Indian tally constitutes over 50 per cent of the worldwide population of the Asian elephant.

India has 32 elephant reserves in 14 states, but studies reveal that 30% of the country’s wild elephants live in large and contiguous forests, while the rest are distributed across fragmented landscapes that have shrunk amid growing human activities, including cultivation.

Bilal Habib, a conservation scientist and member of the elephant cell at the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, was quoted in the media as saying, "The loss of a single older elephant in a herd is the loss of experience for the others in the herd. The older members in the herds guide the younger ones. In their absence, the younger ones could stray into human-dominated landscapes, increasing human-elephant conflict."

Statistics reveal that these conflicts have only intensified. Changes in crop patterns and agricultural management, irresponsible wildlife tourism, the impacts of global warming and in-migration into forest areas have all played a role.

There is more. The fast-dwindling population of wild elephants, or other animals, is not an issue of political significance in India, as animals don't constitute a vote bank! Frankly, beyond a few activists and biologists, no one could care less.

Forest conservationists are correct in suggesting that in a time of escalating human-wildlife conflicts, with wild elephants being felled indiscriminately across the country, a review of forest management policies at the government and community levels is required to save habitats.

Not unnaturally, the electrocution of wild elephants -- the cause of the largest number of deaths -- is being witnessed in areas where rising human-wildlife conflicts have been reported. Unless something is done soon, the growing in-migration levels will only aggravate this conflict.

ALSO READ | Man vs Otter and other Kadalundi tales

Environmentalists have been quick to note that the situation on the ground is alarming. Several development projects have been launched without addressing environmental impacts, causing incalculable damage to wildlife habitats in India.

Some positive steps need to be noted.

The Kerala government has attempted to mitigate the problem, adopting some key measures. It provided 584 km of elephant-proof trenches, installed 1,501 km of solar-powered fences, 35 km of elephant-proof walls, 3.5 km of stone-pitched trenches, 259 km of kayyala and 43 km of bio-fencing to minimise human-wildlife conflicts. The state forest department has also formed Rapid Response Teams to meet emergencies and to work with affected communities.

Interestingly, all solutions are on the table. Someone just needs to implement them. The Environment Ministry has requested states and power transmission agencies to take steps to ensure that transmission lines are at an adequate height from the ground to minimise the risk of electrocution.

A joint advisory from the environment and railway ministries issued 12 years ago had suggested measures to reduce the risk of elephants being struck by trains. Again, government agencies have been dragging their feet over an issue that has little public resonance.

Guidelines issued six years ago, prescribing measures such as underpasses of adequate height for elephants to cross railway lines, have been largely overlooked.

Web Scrawl | Read more of our web-only articles here

With the expansion of cultivated land along forest boundaries, experts say, elephants are increasingly being drawn to forage for crops such as maize, millets, paddy, sugarcane and vegetables.

Conservation scientists have in the past recommended steps to mitigate human-elephant conflict such as bio fencing with certain crops unpalatable to elephants like chillies, ginger or citrus plants or with beehives.

Naturally, any tangible solution has to include the interests of the ever-burgeoning human population. The central government says that compensation is being paid to local communities for any loss of property or life caused by wild elephants to avoid retaliatory killing, which would be adding to the numbers of those dying in the wild.

(Ranjit Bhushan is a senior journalist. These are the writer's views.)