In the nineties, the multinational company I used to work for started its operations in China. Many from the Indian subsidiary were sent there for the start-up. I would be surprised to find they would carry with them suitcase loads of dal. Apparently, our humble lentils were scarce in China, especially in the interior provinces. It seemed strange that when almost everything we eat is supposed to have its origins in China, a common staple like dal was not available. It took some research to realise that if there is one food which Indians can lay proprietary claims on – it is our humble dal.

I would have spared my gentle leaders a discourse on the ancient origins of dal. But a little anthropological detour may not be out of place to establish the impressive antecedents of a food that we take for granted today.

Food historians tell us that references to urad, moong and masoor dal can be found in the Vedas. Allegedly, Bhim cooked panchmel dal in King Virata’s kitchen. Not to be left behind, Lord Ram too relished dal – but as a salad called kosumalli. The recipe is interesting – soaked dal, diced cucumber, a sprinkle of coconut – all of it tossed in lemon juice.

Traces of lentils were found at the Harappan sites in Haryana. There are references to dal in ancient Buddhist and Jain texts too. Something akin to our modern day ghugni was served at Chandragupta Maurya’s wedding feast. Coming to more recent royalty, Akbar’s Rajasthani wife Jodha Bai introduced the panchmel dal (or panchratna dal) to the Mughal kitchen. This was later appropriated by Shahjahan during his incarceration as Dal Shahjahani and later Aurangzeb himself, upon turning vegetarian.

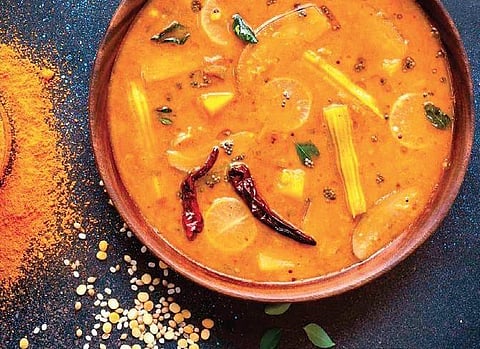

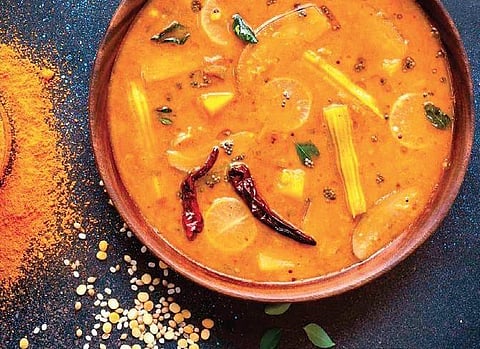

Cut to modern times and dal immediately conjures up images of either the thick rich yellow gravy with oil and tadka floating on top or the heavy brown grainy liquid decorated with cream like a Starbucks latte served in a bowl. But the best dals are light and have a subtle taste of spices. A classic dal has to be enjoyed with plain rice and nothing more -- not even roti. Punjabi rajma chawal, Maharashtrian varan bhat or Bengali sono-mooger dal are great examples. But, perhaps, nothing can illustrate that better than the South Indian sambar. Making sambar is no less than an art form. But sambar itself is not generic. Apart from regional differences within each state -- nay every family -- there are variations of recipe and technique of preparation, which are often a subject of culinary snobbery.

The story of Thanjavur sambar has been done to death -- how Sambhaji’s cooks substituted kokum (used for making Maharashtrian amti, another personal favourite) with tamarind to create the modern day sambar. However, what differentiates one regional or family recipe of sambar is not just the vegetable ingredients -- which change with what is available and popular in those parts -- used but the different kinds of podi (or masala). As one moves westwards and reaches Palakkad, coconut comes into play (either roasted or grated or through the oil) and the tamarind levels go up, as with the ulli (onion) sambar in Kerala. Move further north to Udipi and jaggery inveigles its way into the mix -- so much so that an Iyer friend of mine called it Toor Dal Kheer much to the chagrin of Mangaloreans in the group. Go to Andhra Pradesh and sambar is transformed into pappu, which is thicker but tangier like rasam. Climb further up the Coromandel Coast -- and you have dalma in Odisha. It is a one pot dish made with toor (arhar dal) and an assortment of vegetables typically raw banana, eggplant, green papaya and pumpkins, coconut slices simmered in a special spice blend using “panch-phoron” (Bengali five spices).

The Gujaratis are not just besan fanatics, they are dal connoisseurs too. No other community elevates the khichadi to gourmet levels. While most Gujarati food tends to be a tad sweet, the Surati toor dal is a mix of sweet and sour (khatti-meethi) achieved by a mix of jaggery and kokum. Personally, I find Punjabi dals as over-rated as their paneer. The dal makhani is as much of a popular travesty as the chicken butter masala - both creations of Kundan Lal Gujral of Delhi’s Daryagunj Moti Mahal restaurant fame. I love rajma -- but again the more watery and lighter variety, which I discovered in the dhabas on the way from Pathankot to Jammu and also available on roadside stalls in Delhi.

However, if there was an award for the best dal, it would undoubtedly go to Uttar Pradesh. From the slow cooked dum-pukht chana dal of the Awadhi cuisine to the flavourful Kanpuri arhar made without onion and garlic by the UP Bania community, they fall into a different genre of sophistication. But the most well kept secret is the Dal Moradabadi -- sold from handcarts out of copper vessels (after all it is the city of copper) on leaf plates -- which is a meal by itself. As per legend, it is named after Prince Murad -- the founder of the city and the third son of Shahjahan. It is moong dal cooked for hours with very little spices (mostly ginger, bay leaf, roasted cumin powder and crushed dry red chillies) but served with garnishes like chaat masala, dhaniya (coriander) leaves, green chillies, juliennes of ginger, onion and lemon juice with a generous dollop of ghee. If you are not going to Moradabad in a hurry, you can look out for it at Delhi weddings where 'dal counters' are common these days.

Contrary to popular belief, Bengalis do not eat only cholar dal. The shona (golden) moong dal which is lightly roasted in mustard oil (Biharis do the same) without use of onion, garlic or tomatoes, just a little jeera cumin, hing and a touch of turmeric is the most popular. But ask a ghoti and she will flip for biulir (split urad) dal made with fennel seeds and hing which tastes divine with alu posto. In summers, Bengalis also make a khatta dal using raw green mangoes. However, the high point of a feast is moong dal made with a fish head.

Talking of non-vegetarian dal preparations, the Parsi dhansak and Hyderabadi dal gosht are well known. But without the authentic dhansak masala, everything else is an imposter. Similarly, the dalcha -- which traces its origin to the Middle Eastern harees -- is the precursor of the now commercialised dal gosht.

The story of dal will not be complete without a swig of rasam like any good South Indian meal. Having already exported the mulligatawny soup in the last century, the next will probably be the turn of lentil risotto -- aka khichadi -- to be made a rage by some Michelin-starred master chef.

Read all food columns by Sandip Ghose here

(Sandip Ghose is an author and current affairs commentator. He tweets @SandipGhose.)