The famous British film critic Derek Malcolm said, "Shyam Benegal’s films provided a huge marker for other young directors of what was once hopefully called the Indian parallel cinema." Yet, Benegal himself used to say, "I do not know if there is such a thing as a new wave. Let me put it this way, some people now attempt to make films of their choice, different from the industry’s mould…. And now there is wide range of people, from one end of the scale to the other, who want to make their own kind of films."

This humility, this self-effacing attitude was the hallmark of this great man.

His undisputed greatness was recognized with his first film itself. In 1974, when Benegal’s Ankur (The Seedling) sprouted, it brought a breath of fresh air with its bold and incisive social critique, and its agency against inequality and injustice born out of deep-rooted societal discriminations. The film, which captured this friction caused by caste-distinction, unequal gender relations, tension between modernity and ancient traditions, stands out both artistically and aesthetically. Ankur remains a 'tool-kit' -- to which Benegal went back again and again.

Apart from many new values that Ankur brought to the world of Hindi cinema, it also brought a plethora of new actors, which included a trailblazer who has remained active as an actor and activist -- Shabana Azmi.

A year later came Nishant, which in many ways was a sequel to Ankur. Here the similar theme of feudal exploitation of the rural poor –- especially women –- comes out even more brazenly, brutally, vividly. With two gifted ladies Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil in the film, which boasted of a hugely talented cast, Nishant actually brought a new dawn in Indian cinema. It went on to be India’s official entry in the competition section of Cannes Film Festival in 1976.

To complete an unintended trilogy Manthan arrived in 1976. The film dealt with the churnings in similar social conditions in a Gujarat village, but highlighted very different means employed to bring about change. It explored the ushering in of change through a co-operative society (Amul) for the milk producers of this impoverished region. These milk sellers had till then been exploited by the middlemen and big private companies who were milking these hapless men and women dry.

These films highlighted Shyam the social historian who as Benegal's friend, critic and poet Anil Dharkar commented "looks at the mass experiences of history, through his films".

Early days and the Nehruvian worldview

Benegal had been exposed to the world of visual images, art, painting, photography and films from the very beginning of his life. His father Shridhar Benegal had a small but well-endowed photography studio in Secunderabad cantonment, close to the city of Hyderabad. Painting was Shridhar Benegal’s other passion.

Shyam too was given an 8mm camera to play with, and taught the skills of developing a film and printing on photopaper. His friendship with the projectionist of the Garrison Cinema, in Secunderabad, gave the young Shyam access to world cinema – a la the protagonist in Cinema Paradiso.

Then Shyam went to study economics at Nizam College in the wonderfully charged atmosphere of those days, when as the nation was embracing independence the Nizam and his Razakars refused to align with free India. There were also the communists whose writ ran in the state at night, especially in the Telangana region. In some other parts of the Hyderabad state, the Hindu Mahasabha too had its hold.

It’s this churn that shaped the political sensibilities of the young economics graduate who saw the new India through the Fabian socialist, modernist, egalitarian point of view of the first Prime Minister Nehru. These values are well reflected in his cinema.

Women-centric films and the introduction of AR Rahman

In Bhumika (1977), based on actress Hansa Wadkar’s biography, Benegal chooses to reconstruct the past, harsh present and the make-believe film world in three different tonalities and hues. This artistic decision was made to make good use of the problem -- of obtaining the supply of the rationed raw-stock in mid-seventies. Benegal decided to use the Orvo, Geva, Eastman-colour and black and white stock for different sections of the film. These different hues delineate the lead character Usha’s private, public and past persona very well.

Benegal’s two other films on performing public-women Sardari Begum (1996) and Zubeidaa (2001) are also in a league of their own. The use of music in all three is very evocative.

Zubeidaa saw the introduction of AR Rahman for the first time in a Benegal film - till then the inimitable music maestro Vanraj Bhatia had scored the music for his films. A few people did criticise Benegal for having drifted from the 'parallel’ line towards the mainstream as he used two mainstream actors –- Rekha and Karishma Kapoor -- and a popular music director in Zubeidaa.

'A Gateway to film industry'

The Zubeidaa backlash was in some ways expected as he had only used trained but unknown new faces in his films till then. Indeed such had been his reputation that Benegal was given the moniker of ‘A Gateway to film industry', in the manner of the famed 'Gateway of India’ in Mumbai.

He had been responsible for giving countless new actresses and actors to the Indian cinema, a feat unmatched by anyone else in Bombay’s film world. These include Shabana Azmi, Anant Nag, Priya Tendulkar, Smita Patil, Nasiruddin Shah, Om Puri, Amrish Puri, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Savita Bajaj, Nafisa Ali, Surekha Sikri, Rajeshwari Sachdev, Rajit Kapur, Irrfan Khan and at least a hundred others when he made Discovery of India.

Tryst with Comedy

The 1983 film Mandi marked a new chapter in Benegal's oeuvre -- comedy. Based on a story by Pakistani writer Ghulam Abbas, it was inspired by an actual incident. When Congressmen in Allahabad agitated to shift a red-light area from the centre of the city, someone said, "If you shift a brothel from the city, then the city would also shift itself to the bordello." How one wishes that even an iota of this pragmatism was to be found in today's duplicitous political leaders.

Coming back to the point of comedies, whenever Bengal took that route to tell a story, he was able to tickle the funny bone of his audiences. Apart from Mandi, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008) and Well Done Abba (2009) served as good examples of this.

TV, The Discovery of India and his love for History

With the arrival of television in Indian households in the 80s and 90s, middle-class audiences turned away from the theatres. Benegal analysed he situation thus: "It was evident that the urban audience was cleft into two halves. The middle class stayed loyal to television, (whereas) urban poor returned to the theatres. Soon most of the 'parallel' film makers were to follow the audiences and moved to the television."

And like many of his peers, Benegal also went to television and carved out an enviable niche for himself. He did several series', but what made history literally and figuratively was his 52-episode magnum opus, Bharat Ek Khoj (1988-89) based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s book, The Discovery of India, that covered 5000 years of India’s history.

History attracted him like no other subject. But his historical films can be categorised into two sections. One, the period dramas, where he located a subject in a certain past but took the liberty to construct his own self-devised narrative. And then his 'histories' where he took material directly from history books and dramatised them with as little deviation from the historical accounts as possible.

Films like Junoon and Zubaidaa would fall in the first category of "period pieces".

Then there are the 'pure' histories and biopics, where after deep research he stuck to the facts, figures, dates, places as far as possible.

I had the good fortune of working with him in several histories and biopics. I am especially proud of a 10-hour-long film Samvidhaan that I wrote for Benegal, with his long-time associate Shama Zaidi in 2014. It's the story of the making of the Indian Constitution.

Similarly, his two biopics are in a class of their own. The Making of the Mahatma, based on a book by Fatima Meer, and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero, which had the longest title.

Benegal and his many experiments

One inimitable attribute of Benegal was the eagerness to experiment with forms, genres and narratives. Films like Arohan and Sooraj Ka Saatvan Ghoda are examples of that.

The 'film within a film’ form is used by Benegal in his film Samar, where he once again visits the caste question that continues to divide Indian society despite the constitutional guarantees available to us for the last 75 years.

There are too many other gems to be talked about.

Charandas Chor, a children’s film with several tribal actors and Smita Patil, who was seen on the big screen for the first time.

Then Mammo, a film about the lived experience and continued pain inflicted by the partition of India, even decades after it took place.

Trikal about the days when India got Goa liberated from the Portuguese and Antarnad about the life-changing Swadhyaya movement in Gujarat are both unforgettable.

Susman about a master weaver and his pitiable position in the world of haute couture and Hari-Bhari about the reproductive choices of women folk in a Muslim household triggered many debates.

'That widest of trees with a thousand roots and shoots'

Benegal is also credited with almost two hundred documentaries of various lengths, dealing with different subjects. Then there are his short films.

It has indeed been quite a journey by that young man from Secundarabad, who reached Bombay with a one-way ticket gifted by a friend. Even back then Benegal was clear on what he wanted.

He did not want to assist his first cousin Guru Dutt, since he did not want to make films mimicking those made by the director of classics like Pyaasa. He joined an ad agency instead. As he said himself, "I was making ad films for two reasons: One that I was good at them, but more than that, it was helping me train as a filmmaker."

And what a filmmaker he turned out to be!

I would like to quote one of Benegal's favourite actors Om Puri to give a glimpse of his greatness. Puri, in his inimitable style, once said, "In the jungle of Indian cinema there are thousands of trees of various kinds. But the tallest of them is Satyajit Ray. And the widest of them, like the banyan in Calcutta’s botanical garden, is Shyam Benegal -- with a thousand roots and shoots."

With these words, I pay my respects to my mentor and guru, with whom I have worked since 1988, when he made me write for Bharat Ek Khoj. Last year, at the age of 89, he finished and released his latest, biggest, costliest international collaboration, Mujib: The Making of Nation, that too in a new language -- Bengali.

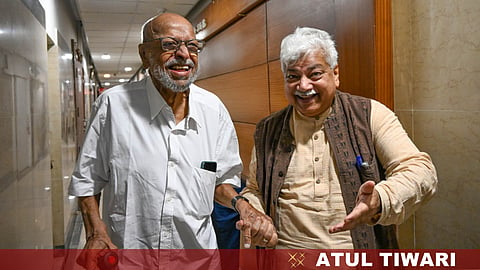

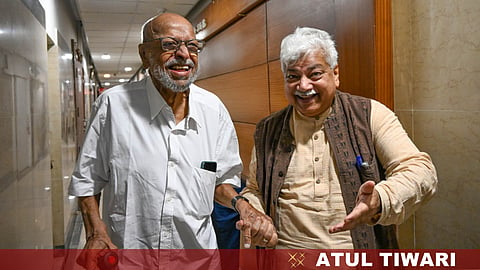

I can never forget how only 10 days ago, on his 90th birthday on December 14, he came specially to his office to accept my gift for him, the book MAESTRO: A tribute to Shyam Bengal at 90, which I had written for the occasion. He was all smiles as he looked at the book, and I can't forget how he turned emotional seeing the photographs of his parents.

As he leaves us shocked and saddened by his departure, I can only say, "Long live Shyam Babu. You are a story well told."

(Atul Tiwari began his film career with his guru Shyam Benegal in 1988. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero, the film that he co-wrote with Shama Zaidi and that was helmed by Benegal, won the Nargis Dutt Award for Best Feature Film on National Integration. He was also a co-writer of the Kamal Haasan-film Dasavathaaram and has worked with filmmakers like Vidhu Vinod Chopra.)