Lucius Cincinnatus, a Roman statesman and military legend who lived in the 5th century BCE, is considered the embodiment of glorious civic virtue and renunciation of political power.

As Roman forces struggled to defeat the Aequi, a formidable Italic tribe, Cincinnatus was summoned from his plough to assume the dictatorship of the Roman Republic. After achieving a swift victory in sixteen days, Cincinnatus relinquished power and its privileges, returning to labor on his humble farm.

Joseph Howe, a Canadian poet and politician, portrayed the Cincinnatus myth in the following verse: “The purple robe was o'er him flung/They hail'd him Chief in Rome/But yet a tear unbidden sprung/He sigh'd to leave his home.”

Cincinnatus's military triumph and his immediate resignation of the absolute authority at the end of the crisis have often been cited as a model of selfless leadership, civic virtue, and service to the greater good. The story has also been seen as an exemplar of agrarian virtues like humility, modesty, and hard work.

Yet the tale of Cincinnatus saving the Republic from invaders is only half of the story, for he was named dictator of Rome not once but twice. The first time, Cincinnatus rallied Rome’s defences against an external enemy. The second time, as described by Roman historian Livy in his Ab Urbe Condita (From the Founding of the City), the danger was domestic.

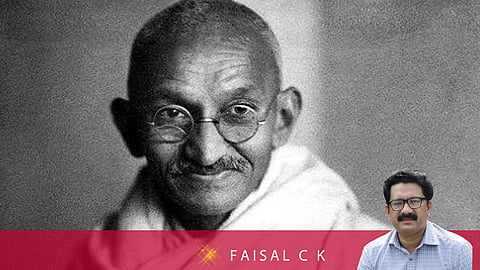

Resembling Cinicinnatus, Mahatma Gandhi was called to lead the desperate struggle against the nearly-invincible British imperialism. His persistent struggles from the passive non-cooperation to the ‘Do or die’ Quit India Movement drove the Raj out of Indian soil. Thereafter, like Cincinnatus, he channeled his efforts to quell the wildfire of communal hatred, the domestic enemy, unleashed by the Partition. He abjured political power and opted for his simple Charka just as Cincinnatus returned to his plough.

Cincinnatus and Gandhi were more the heroes of mankind than mere leaders.

“The hero sacrifices himself for something - that’s the morality of it. He gives his life to something larger than himself. In further contrast, the hero symbolizes our ability to control the irrational savage within us, whereas the leader may exploit the savage to gain his ends...The hero’s humility, loyalty, temperance, and restraint are timelessly virtuous. Such virtue is expressed so vividly that its importance, as evident in the Cincinnatus example, resonates beyond even the next millennium, and survives in the human race potentially forever,” writes Michael J Hillyard in his Cincinnatus and the Citizen-Servant Ideal: The Roman Legend's Life, Times, and Legacy (2001).

Cincinnatus and Gandhi valiantly fought against their rivals; meanwhile, they were kind enough to forgive their foes.

The power of renunciation

Cincinnatus’ bravery, soldierly skill, and trustworthiness made the city’s leaders feel as though he should be declared King of Rome. True to his humble form, Cincinnatus declined the offer and asked only to return to his farm where his wife Racilla and honest hard work awaited him. So did Gandhi; when India gained independence and Delhi was jubilant, he retired to the hamlets of Bengal to continue his service to the common folk. He scrupulously kept aloof from the corridors of power. Overcoming the lust for power is hard for leaders, but easy for heroes like Cincinnatus and Gandhi.

As a philosophical anarchist, Gandhi believed that the essential nature of the state was striving for more concentration of power and conceived the state as egoism writ large. He concedes the point that the pursuit of power is an endemic human desire but was equally careful in emphasizing the countervailing and more effective role of moral values which may create a new category of power that will be in consonance with individual fulfillment and a humane collective face. Renunciation of political power invigorates the moral and spiritual powers of individuals. The moral and spiritual prowess of the individual is the center of Gandhi’s scheme of things.

Gandhi approaches politics in a religious spirit: “I could not be leading a religious life unless I identified myself with the whole of mankind and that I could not do unless I took part in politics. The whole gamut of man’s activities today constitutes an indivisible whole….I do not know any religion apart from activity. It provides a moral basis to all other activities without which life would be a maze of sound and fury signifying nothing.”

The Gandhian concept of religion is not sectarian but universal, encompassing all humanity. When Gandhi stresses on religion as the bedrock of politics, what he means are religious values that are common to all religions rather than any kind of sectarianism.

The Christian ideal of renunciation has a significant role in the Gandhian concept of religious politics. As The Book of Common Prayer indicates, renunciation rests at the heart of the Christian identity. Hence, the renunciation of and detachment from political power is a major doctrine of faith in Gandhian philosophy. It promotes the purity of the individual soul and selfless civic virtue that wipes out egoism and selfish materialism. Civic virtue is the cultivation of habits important for the success of a society. It is often conceived as the dedication of citizens to the common welfare of each other even at the cost of their individual interests.

Embodying their philosophy

Gandhi theorized the nature of political power and authority keeping in mind his commitment and preference to anarchist ideals of how to ensure a wider diffusion of power to realize justice in society. His essential distrust of power and authority led him to articulate an alternative which he called enlightened anarchy. This enlightened anarchy is anchored in selfless civic duty and virtues like humility, modesty, and hard work as Cincinnatus practised in ancient Rome.

The saying “Don't explain your philosophy. Embody it,” is attributed to Epictetus, a Greek Stoic philosopher. This is a call to action, recognizing that actions speak louder than words. Instead of merely explaining one’s philosophical or ethical stance, the emphasis is on demonstrating that stance through behaviour, choices, and interactions with the world. Cincinnatus and Gandhi embodied their philosophy of detachment from political power and an unwavering commitment to civic virtue. They were ideal citizen-servants worth adulation and emulation. If the world's citizens follow their less-trodden path, the world would be far better than ever.

(Faisal C.K. is Deputy Law Secretary to the Government of Kerala. Views are personal. Email: faisal.chelengara10@gmail.com )