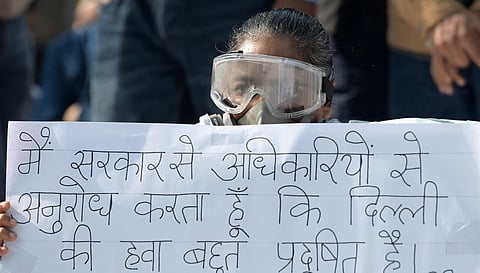

Delhi's poisoned air and the failure of Indian environmentalism

Every winter, Delhi becomes a gas chamber. The air thickens, the horizon disappears, lungs burn, and schools shut down. Political leaders exchange accusations, courts issue stern directives, and television studios discover the language of apocalypse. And then, when the winds change, the crisis recedes from public memory, only to return with grim predictability the following year.

The pollution of Delhi and the wider National Capital Region is often described as a seasonal problem. This is deeply misleading. What we witness each winter is not a sudden catastrophe but the visible manifestation of a long and cumulative failure: of governance, of planning, of environmental imagination, and of civic responsibility. The smog is merely the final symptom of a deeper disease.

To understand Delhi’s air, we must first understand Delhi itself: a city built too fast, governed too loosely, and inhabited too unequally.

A City Outgrowing Its Ecology

Delhi has never been an easy place to live in ecological terms. It sits in a semi-arid zone, dependent historically on the Yamuna and on seasonal winds for renewal. Pre-colonial settlements were compact, shaded, and built around water bodies. The British imperial capital, for all its excesses, still maintained tree-lined avenues and clear spatial zoning.

Post-Independence Delhi, however, grew without ecological restraint. Its population has multiplied more than tenfold since 1951. The National Capital Region was conceived as a buffer to this growth, but instead it became an extension of the same ecological chaos. Farmlands gave way to real estate, wetlands to highways, forests to concrete.

This relentless urban expansion has exacted a severe environmental cost. Vehicular emissions dominate the pollution load. Construction dust is omnipresent. Industrial clusters, relocated in theory, continue to operate in practice. The city’s green cover exists largely on paper, while its water bodies have been reduced to drains.

When winter arrives and atmospheric conditions trap pollutants close to the ground, the city’s accumulated sins become unbreathable.

The Convenient Villain of Stubble Burning

Public discourse on Delhi’s pollution requires a villain, and every year it finds one in the farmers of Punjab and Haryana. Stubble burning does contribute to the problem. Satellite images and air quality data leave little doubt about this.

But to focus obsessively on farmers is to commit a moral and analytical error. The practice of burning crop residue is itself the result of policy decisions taken decades ago. The Green Revolution promoted monoculture, water-intensive crops, and mechanised harvesting. Farmers were encouraged to grow rice in regions ecologically unsuited for it. They were given neither viable alternatives nor adequate compensation to manage crop waste sustainably.

Blaming farmers for air pollution while ignoring the policy architecture that trapped them is both unjust and ineffective. Environmental crises are rarely caused by individual malice. They are produced by systemic incentives gone wrong.

The Automobile as Sacred Cow

If stubble burning is a seasonal contributor, private vehicles are a perennial one. Delhi has more cars than Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata combined. Flyovers multiply, road widths increase, yet congestion worsens. Each new road induces more traffic, a fact well known to urban planners and persistently ignored by politicians.

Public transport, despite the undeniable success of the Delhi Metro, remains inadequate for a region of this size and density. Bus fleets have shrunk rather than expanded. Pedestrians and cyclists are treated as inconveniences rather than citizens. The middle classes, who dominate public discourse, demand cleaner air while insisting on the right to drive everywhere.

Environmentalism that refuses to question private consumption is environmentalism in name alone.

Courts, Committees, and the Illusion of Action

India has no shortage of environmental regulation. There are action plans, task forces, graded response mechanisms, and judicial orders. What we lack is implementation with continuity and accountability.

The Supreme Court and the National Green Tribunal have stepped into the vacuum left by executive failure. Their intentions are often laudable, but courts cannot govern cities. Judicial interventions tend to be reactive, episodic, and blunt. They may ban diesel generators or halt construction temporarily, but they cannot redesign transport systems or reform urban governance.

Moreover, governance by emergency creates the illusion of action without addressing root causes. Smog towers are erected as symbols of resolve, though their impact is negligible. Odd-even traffic schemes are announced, though evidence of their effectiveness is mixed at best. These measures reassure anxious citizens without challenging the structures that produce pollution.

The Inequality of Breathing

Air pollution is often described as a “great leveller,” affecting rich and poor alike. This is only partly true. The wealthy retreat into air-purified homes, sealed cars, and private hospitals. The poor continue to work outdoors, cook with dirty fuels, and live near highways and industrial zones.

Children from low-income families suffer higher rates of asthma and impaired lung development. Migrant workers have no option of leaving the city during peak pollution. For them, the smog is not an inconvenience but a daily assault.

Environmental degradation in India, as elsewhere, mirrors social inequality. Those who contribute least to the problem suffer its worst consequences.

A Historical Failure of Environmental Politics

India once had a vibrant environmental movement. From Chipko to Silent Valley, from the Narmada Bachao Andolan to campaigns for urban commons, environmentalism was rooted in questions of justice, livelihoods, and long-term sustainability.

Today, environmental politics has been hollowed out. It oscillates between technocratic managerialism and symbolic nationalism. Ecological concerns are framed as obstacles to development or reduced to matters of individual behaviour: bursting fewer crackers, switching off engines at red lights.

What is missing is a serious public conversation about limits: limits to growth, limits to consumption, limits to ecological exploitation. Delhi’s air crisis is not merely a failure of policy but a failure of imagination. We have refused to ask how large a city can grow, how many cars it can absorb, how much pollution it can tolerate.

Towards a Breathing City

Cleaning Delhi’s air will require more than emergency measures. It demands structural change sustained over decades.

First, urban planning must be reclaimed from real estate interests and short-term political calculations. Green spaces, wetlands, and floodplains must be protected not as luxuries but as life-support systems.

Second, public transport must become the backbone of urban mobility. This means massive investment in buses, last-mile connectivity, and non-motorised transport. It also means disincentivising private vehicle use through pricing, parking regulation, and urban design.

Third, regional cooperation must replace competitive federalism. Delhi’s air does not respect state boundaries. Pollution control requires coordinated action across the NCR, backed by shared funding and authority.

Finally, environmentalism must be democratised. Citizens must see clean air not as a favour granted by courts or governments, but as a right that carries responsibilities. This includes rethinking lifestyles, consumption patterns, and political priorities.

A Moral Test

The pollution of Delhi is often framed as a technical challenge. It is, at heart, a moral one. It asks whether we are willing to place long-term collective well-being above short-term individual convenience. Whether governance can rise above blame-shifting and symbolism. Whether development can be reimagined without ecological self-destruction.

Future historians may judge our generation harshly. We knew the damage we were causing. We had the data, the warnings, and the examples from other cities. Yet we allowed our capital to become a place where breathing itself is an act of endurance.

A city that cannot guarantee clean air to its children has failed a basic test of civilisation. Delhi’s smog is not merely an environmental crisis. It is a mirror held up to the republic, reflecting the costs of our neglect and the urgency of our choices.

The air we breathe today will shape the citizens we become tomorrow.

(The author writes on society, literature, arts and environment, reflecting on the shared histories and cultures of South Asia.)