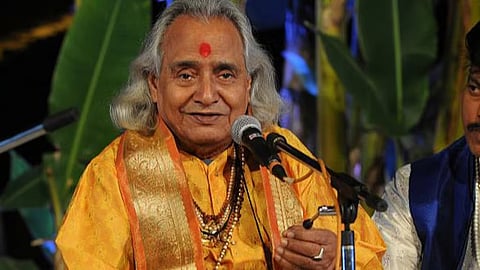

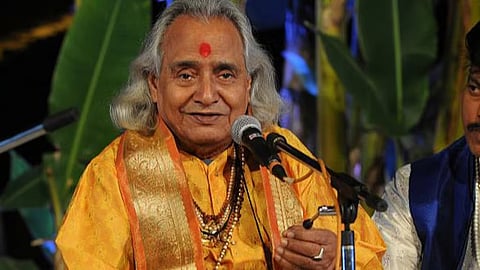

Padma Vibushan Pandit Chhannulal Mishra's end had been slow and visible, like the dimming of a lamp that had burnt far too long, devoted and steady. Frailty had gripped him in the last months, but the voice that once seemed inseparable from the soundscape of Banaras had long entered the realm of memory.

For Banaras, Mishra’s death at the age of 89 on October 2 feels like the loss of grammar itself. His was not just a celebrated career; it was a way in which the city came to hear itself.

A life rooted in song

Born on August 3, 1936, in Hariharpur village of Azamgarh district, Chhannulal Mishra was born into music as one is born into a dialect. His early training was under Pandit Badri Prasad Mishra and later Pandit Damodar Mishra, rigorous masters of the Banaras gharana. He absorbed not just the khayal tradition but also the subtle inflections of the Kirana style, making him fluent in multiple vocabularies of Hindustani music.

The Banaras gharana has always stood apart: earthy, emotive, unapologetically expressive. What Chhannulal Mishra carried forward was its deep interweaving with the Purab Ang, thumri, dadra, chaiti, kajri, the seasonal songs that smell of rain, of festivals, of human ache. Where others drew stark lines between “serious” khayal and “lighter” thumri, Mishra bridged them seamlessly. For him, these categories were not hierarchies but shades of the same truth.

The sound of a city

To listen to Mishra was to hear Banaras itself. His meends resembled the river’s glide; his pauses carried the hush of dawn over the ghats; his thumri contained the sly melancholy of street conversations, or the unspoken sighs of waiting courtyards.

It was not mere artistry, but a form of belonging. When he sang, he turned the geography of Banaras into music: the sound of temple bells, the fragrance of incense, the strange simultaneity of mourning and celebration that marks the city. The ghazal singers of Lucknow often spoke of refinement, Mishra’s singing spoke of endurance. It was a voice carved out of daily life, not ornamentation but testimony.

Recognition and reach

Recognition followed slowly but surely. The Padma Bhushan in 2010, the Padma Vibhushan in 2020, India’s second-highest civilian award, and the Sangeet Natak Akademi fellowship were the official markers. He was a fixture at classical music festivals, from Dover Lane to Sawai Gandharva, and carried his art abroad to diasporic audiences hungry for the sound of home.

But to confine his reach to prizes is to miss the point. His true achievement was in how he made these traditions legible to generations who were losing the patience for long-form classical recitals. He taught them that the slow unfolding of a raga, the disciplined meander of a khayal, was as thrilling as any modern spectacle.

The guru's severity

Those who studied under him remember his unsparing severity. A riyaaz missed was, for him, a breach of faith. A note sung without care was a moral lapse. Disciples recall how, after hours of practice, he would halt the room to correct a single intonation, not out of pedantry but because precision mattered as much as devotion.

Yet he was not austere without warmth. Between scoldings came laughter, tea, and gossip. He carried into his home the double life of Banaras itself: stern in discipline, relaxed in living. His son, the tabla player Ramkumar Mishra, often described how the household was filled with music but also with the noise of markets, festivals, and grandchildren.

Politics and public embrace

In later years, Mishra became close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who often cited his affection for the maestro. He was celebrated as a “cultural ambassador of India.” Some found this proximity to power dissonant; others saw it as natural, given how deeply his art spoke to the idiom of Kashi that Modi himself tried to embody.

What cannot be denied is that Mishra wore the mantle easily. He had always believed that music was not only private expression but also public heritage. If his association with power ensured that thumri and dadra remained audible in national consciousness, he accepted it without hesitation.

The intimacy of his voice

Strip away the state ceremonies, however, and what remains is intimacy. Listen to his rendering of “Jiya Lage Na” and you will hear not grandeur but a confessional hush. His was a voice that sounded private even on a stage of thousands. He could make you feel he was singing to himself and you were merely eavesdropping.

This paradox, the vast raga made intimate, was his gift. He made complexity human. In him, music became less about performance and more about presence.

The fragility of transmission

His passing is not merely the loss of a person but of continuity. The Purab Ang forms he embodied have few successors of his depth. Each great singer is not just an archive of compositions but a method of correction, a sensibility of pause and emphasis that no recording can replicate. That pedagogy now risks dilution.

His disciples will continue. His recordings will endure. But with his departure, the oral and affective knowledge, the tiny corrections, the affectionate rebukes, the embodied transmission, vanishes irretrievably.

The many tributes

Tributes came swiftly after the great man's passing.

The Prime Minister called him “the eternal voice of Banaras.” Cultural institutions lamented the loss. Younger musicians called it a void impossible to fill. But perhaps the truest words came not from officials but from the poet, critic and culture theorist of Banaras Vyomesh Shukla, who has long chronicled the cultural and emotional texture of Banaras:

“Chhannulal Mishra’s voice was a map of Banaras itself, fissured, patient, luminous. When he sang a thumri, you heard not only love and longing but the stubborn resilience of a city that knows how to turn sorrow into melody. He taught us that music is not escape but memory, that a note can be both wound and balm.”

In that bite lies the truth of his legacy.

More than a musician

It is tempting to remember him as just a maestro. But those who knew him insist on another picture: a man who loved paan, who enjoyed small jokes, who lingered in markets. Genius is rarely pure abstraction; it lives in the ordinary. For Mishra, that ordinariness was as essential as his craft. He carried both with equal ease.

Banaras will go on. Its ghats will fill at dawn. Its bells will continue their argument with silence. Its festivals will still demand music. But something has shifted: a sound has gone out of the city’s chest.

The legacy lives

And yet, music, unlike its makers, refuses to end. Play his slow elaboration of Raga Yaman, and he is here again, unhurried, exacting, shaping silence into meaning. His voice remains an inheritance, unquiet and necessary.

Pandit Chhannulal Mishra has left the stage. But the tanpura still hums in the background, waiting. Those who learned from him, those who listened to him, those who will stumble upon his recordings decades from now, all will find, in his music, the sound of Banaras still alive.

He is gone. And yet, he remains.

(Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is a bilingual writer, literary and culture critic based in Bangalore.)