BAKU: Extreme heat ruined the pineapples on Esther Penunia's small farm in the Philippines this year. While it wasn’t a catastrophe for her, since she doesn't rely on the farm for income, she worries about millions of small farmers in her region who depend on rice paddies, coconut groves, and vegetable patches, all increasingly threatened by climate change.

This concern is why Penunia, secretary general of the Asian Farmers Association, hopes this year’s United Nations climate summit will allocate funds to agriculture and the smallholder farmers who feed much of the world.

“You don’t help small farmers, where will you get your food?" Penunia asks. "Who will farm for you? Who will catch the fish, get the honey, or plant your vegetables?”

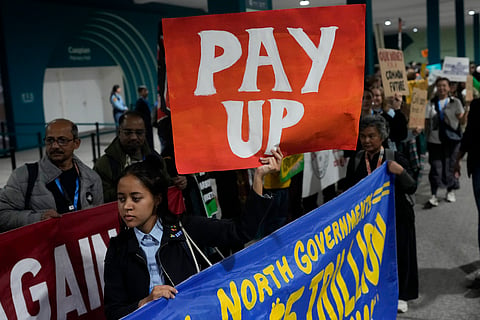

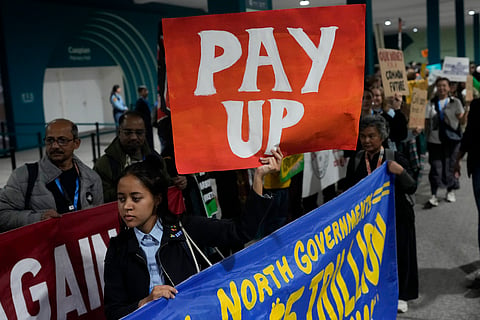

Many countries, particularly in the Global South, require funding to recover after typhoons destroy fields, insure farmers against worsening droughts, and prepare for a hotter climate with better seeds, fertilizers, and water infrastructure. However, there’s a massive gap between the $1 trillion poorer countries need for climate action and what wealthier nations are willing to provide, according to World Resources Institute experts.

Any deal reached will need to stretch the available funds. There’s ongoing debate about how much money should go toward agriculture versus reducing fossil fuel emissions.

Currently, small farmers receive less than 1% of climate finance, according to a report by the Climate Policy Initiative. Yet, food systems which include the processes of growing, transporting, and disposing of food account for about a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

As the planet heats up, farmers’ efforts to adapt become more challenging. Ismahane Elouafi, executive managing director of CGIAR, a global agricultural research partnership, noted at a COP29 panel on climate-smart solutions for smallholder farmers, “If we want to solve the issue, how could we not invest in a sector that is having a third of the problem?”

Praveena Sridhar, chief science and technical officer of Save Soil, argued that funding agricultural adaptation is a simpler, more actionable step. “We have not figured out the [climate] puzzle yet,” she said. “Why not look at the puzzle pieces we have figured out and start moving?”

However, some worry that focusing on agriculture could distract from the larger issue of fossil fuel emissions. Zeke Hausfather, a research scientist with Berkeley Earth, pointed out that land management changes could reduce global carbon dioxide emissions by around a billion tons annually a small fraction of the 40 billion tons emitted each year. He also cautioned that carbon stored in soil through climate-conscious agricultural practices isn’t guaranteed to stay there permanently, referencing a paper he published recently.

Despite such concerns, some countries, companies, and private investors are already committing significant funds to agricultural technology. For example, COP28 announced $9 billion for a U.S.-U.A.E.-backed project to innovate in farming and food systems to adapt to climate change and reduce emissions.

With political uncertainty in the U.S., Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack stressed the importance of sustaining climate-related agricultural initiatives through collaboration across levels of government. “There’s going to be a lot of activity in cities and states that will complement these initiatives,” he said.

The stakes are high for advocates like Penunia, who was disappointed by the lack of attention to farmers at previous U.N. climate talks.

“We hope that really we can be heard," she said.