A hundred years later, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre continues to haunt the collective consciousness of a country's people. Although well known, the events of April 13, 1919 and what preceded them remain poorly understood, says historian Kim Wagner. In his latest book, Jallianwala Bagh: An Empire of Fear and the Making of the Amritsar Massacre, a scholarly and strictly unsentimental account, Wagner presents a sombre reality of the vulnerable position of the British in India amidst the empire's racist fear triggered by the bloody 1857 Mutiny, leading to the colonial brutality.

Excerpts from an interview:

You describe the Jallianwala Bagh massacre as both a catalyst for India's freedom struggle as well as a 'historically meaningful event in its own right.' Can you elaborate?

Nobody in 1919 realised that the events at Amritsar would have such a major impact on the future of the British Raj - or that people would be talking about it a hundred years later. It is important to distinguish between the significance accorded to historical events decades later, and the events themselves as they unfold.

We've heard very little about what happened on April 10, 1919, three days before the massacre...

There were violent riots in Delhi on March 30 and in Lahore and elsewhere subsequently, including in Amritsar on April 10 - so the reality of Gandhi's passive resistance movement was rather more complicated. The key thing to remember, however, is that Indian violence in each and every instance was precipitated by British actions.

You have devillainized General Dyer in order to show how he was just an enabler of the colonial vision. How have people reacted to this nuanced version of Dyer?

There is no question that Dyer was responsible for the massacre, but I think it is important to understand that his mindset was shared by many of his fellow British officers and that there was nothing uniquely 'evil' about him. People like to think of him as a sort of pantomime-villain, the way he is depicted in the Gandhi movie for instance. But we need to understand that his actions were in full keeping with the mindset and logic of colonial violence and that - sadly - there were many like him in India and throughout the Empire.

You've explained in the book how the Rowlatt Act, which played a role in the Amritsar massacre, was totally avoidable. Why?

There were no revolutionary movements active in 1919 and the unrest in Punjab was dealt with under the provisions of the Defence of India Act of 1915 which were still in force. The Rowlatt Act was never used and was indeed withdrawn a few years later - which means that the entire thing could have been avoided.

Theresa May recently expressed 'regret' over the massacre, calling it a "shameful scar" on British Indian history. You speak of then PM Winston Churchill and what went wrong in his 'apology speech'. How do you view these two different statements?

Churchill emphatically did not apologise and his speech in 1920 singled out Dyer as a rotten apple, while the Empire itself remained morally untarnished. Theresa May repeated the same kind of rhetoric and never indicated that Britain and the British Empire had any responsibility or that an apology was due.

You write that some instances are to be remembered, and some wounds are to never be opened. In this context, what sort of apology/reparations do the British owe Indians?

I think the British owe Indians to face up to the past, rather than merely making some kind of mealy-mouthed non-apology. We also have to remember that if an apology was made (and I don’t think it will), it would probably serve to gloss over the history of the Raj and those of a pro-Empire inclination would able to say 'we've apologised so now let's move on and forget it'.

In the light of Brexit, how dangerous is empire nostalgia, which is taking over the world now?

Like any kind of nationalist myth-making, it plays a big role in everyday politics. I think that attempts to rehabilitate the British Empire as a powerful force for good in the world go hand in hand with Britain's decline as a global power – empire nostalgia is thus a symptom rather than a cause.

In terms of politics of space, how is the site of the violence viewed today? And how, in your opinion, should it be perceived?

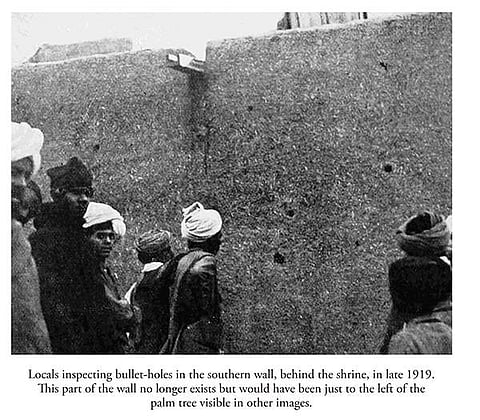

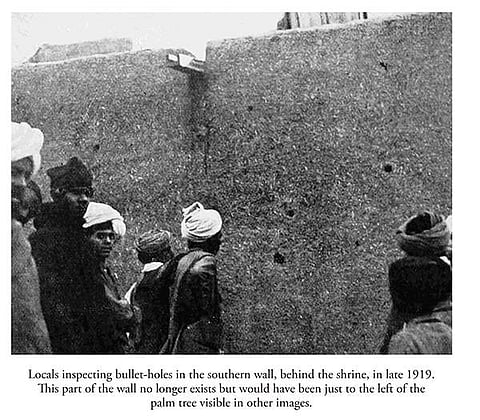

The site of the memorial at Jallianwala Bagh has been transformed into a celebration of the independence struggle rather than a memorial to the people who died in 1919. None of those killed on April 13 were calling for independence and it is only after 1947 that the Jallianwala Bagh massacre could be identified as the beginning of the end of British rule in India. For me, there is very little left of the original historical site and there are few attempts at preserving it properly.

In the centennial year of the massacre, what do you want readers of the book to ruminate upon?

There are many myths surrounding the massacre, and I think the best way of remembering those who died a hundred years ago is by understanding the historical facts and what actually happened. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre was indisputably an atrocity and there is no need to exaggerate the horrors of that day.

Title: Jallianwala Bagh: An Empire of Fear and the Making of the Amritsar Massacre

Author: Kim A. Wagner

Publisher: PENGUIN

Price: Rs 599