Crisis is a feel-good factor in India’s political economy. The truism was validated again last week. The spectre of low growth, poor demand and flagging investment propelled the government to bite the proverbial bullet. It cut the corporate tax rate to 22 per cent for those willing to forego exemptions, aligning it with the competitive emerging economies. The announcement, timed to perfection for the global stage, lifted sentiments and stock indices.

There is much debate and lather on the cost and the benefits. Muddying the froth is an unexplained estimate of the hit on revenues—of `1.45 lakh crore. The sloganeering of higher growth due to tax cuts is an iffy rhetoric given the existential crisis many sectors are enveloped in. The cost and benefits depend on a number of known unknowns. The result of a similar initiative, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the United States in 2017 reveals mixed results.

When initiated it triggered intense debate—the ayes saw a big boost in incomes and investments and the naysayers lamented it would benefit only the fat cats. The fact is neither side turned out to be totally wrong or right—the big corporates such as Apple pushed buybacks for shareholders, but there was also a bump up in capital investments thanks to demand growth.

The brutal fact about a tax cut is that the benefit depends on realised income growth. Job creation and investments depend on expectations of demand growth. The helicopter economics of the political move has critics suggesting alternative modes of stimulating the economy. It is argued that the stimulus of Rs 1.45 lakh crore could have had a direct impact on demand and, therefore, investments if money was transferred into the hands of the consumer.

Relevant analysis of history, though, shows the story is not so linear. Consumption depends on ability to spend and desire to consume. A tax cut improves ability but does not necessarily nudge desire to consume—that depends on expectations of uncertainty or well-being. The 2002 Bush regime tax cut in the US showed a bias for savings—of course higher savings enable deeper capital pool and future productivity and investments.

Regardless of ideological stances, the cut in corporate tax rate is a paradigm shift and sets the stage for investments—by global companies on the supply chain, start-ups and MSMEs. It also allows existing enterprises willing to migrate to a no-exemption regime to realign their cost structures and be price competitive. Whatever the near-term costs and impact, the potential benefits in the medium and long term are undeniable.

The hype, hurrahs and hoopla aside, the harsh truth is that the tax rate cut alone is not enough to lift the economy from its current orbit into one that is more productive and delivers higher growth. The template needs a series of reforms—particularly to sustain the government’s revenue-expenditure model—and to propel demand, investment and job creation.

The critical strength of India’s political economy is democracy, demography and demand. The migration of investment to new supply chain destinations, following the evolution of costs in China, presents an opportunity for India to capitalise on. This demands a radical approach to improving the ease of doing business. Neither the gaming of global rankings nor the three-legged race at home across states delivers meaningful progress. The fact that projects of government-owned enterprises (MOSPI report) are stalled and struggle to get clearances— even for water and electricity—says a lot about the state of ease of doing business.

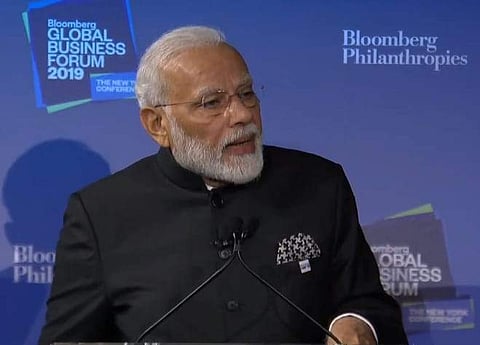

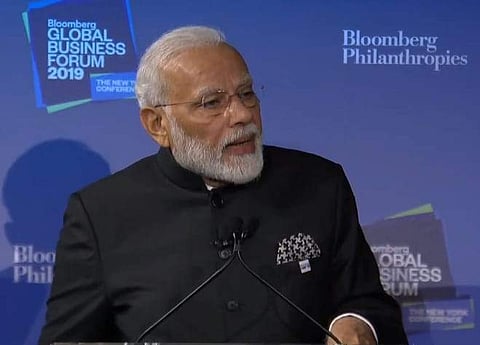

Earlier this week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi assured investors in New York, “If there is any gap anywhere, I will personally act as a bridge.” This promise calls for line ministries, so far comatose, to be pillars of the bridge in shedding old control mindsets and multiplicity of clearances. Must clearances for a hotel or a manufacturing plant travel multiple times from state capital to national capital? An effective approach would be to focus on export orientation and digitisation of the economy. No economy can claim to be global without being globally competitive. Why not look at export-competitive sectors, do a flow chart of clearances and trim them? Why not enable plug-and-play zones for investors to come into?

Once they are set up, there is the spectre of inspector raj. A study circulated within the government throws up a shocking picture. Enterprises, rather businesses, in India, are subject to 91 central laws and 31 state laws and 1,984 compliance requirements.

Clearly, many must live with all 1,984 requirements. But even if an enterprise is subject to 10 per cent of the compliances, that is 198—that is one every two days in terms of resource time. The magnitude of regulatory cholesterol calls for an angioplasty if not an outright bypass!

Finally, no economy can grow if the government persists with and perpetuates wastage of scarce resources. On Thursday, an anonymous finance ministry official declared "the government is absolutely committed to privatisation”. Why must the shift in policy be anonymous? It is not just privatisation which reeks of wastage.

The government needs a new blue book of processes and protocols on expenditure. The aspiration for the $ 5 trillion economy demands not just milestones but continuous reforms.

shankkar.aiyar@gmail.com