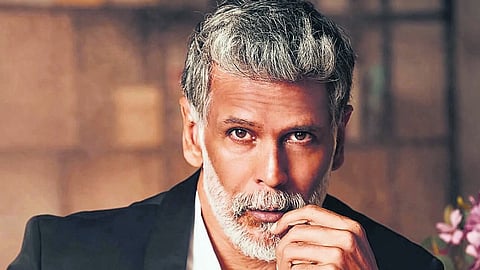

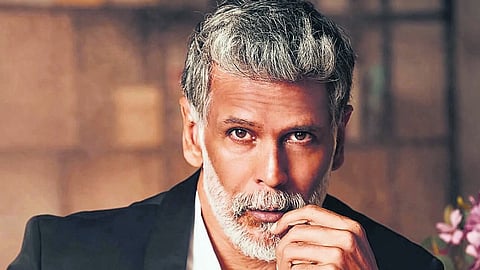

Before the sun rises and illuminates Hyderabad in hues of pink, many thousands of women will gather not to compete against one another, but to take advantage of their rights — to occupy space and their minds. Pinkathon is returning with its sixth edition, scheduled on February 14 and 15, 2026. At its heart is actor, entrepreneur and fitness advocate Milind Soman, who sees Pinkathon not as a milestone, but as a living journey, one that gives women the space and confidence to rise, step by step.

Long before Pinkathon existed, Milind was drawn to creating experiences. “I started event management in the late 1980s, and I found it very exciting to create experiences — for myself and for other people,” he begins in an exclusive chat with CE. Nearly two decades later, when running became a part of his life, one absence stood out: “I noticed women were hardly participating in running events — maybe 4 or 5 per cent.”

That realisation stayed with him. He wondered whether the lack of participation came not from inability, but hesitation — from spaces that did not feel welcoming. “I felt that if I created a space only for women, maybe they would respond. When the first Pinkathon was organised in 2012, the response was immediate. It addressed a lot of resistance that women had,” he recalls.

Those barriers were both visible and invisible. “One was safety — too many men at events, families feeling women may not be completely safe. The other was discomfort — fear of being watched, judged or laughed at. A women-only event removed that pressure. They felt comfortable, and the excitement was incredible,” he highlights.

What followed was organic growth. “From city to city it just kept growing. That’s how we’re here today,” says the actor of Made in India song fame. For him, the power of such events lies in what they offer — direction, community and belief. Pinkathon was always meant to be a beginning. “It started as an event for beginners, women taking their first step towards fitness,” he explains. Distances were accessible: 3 km, 5 km and 10 km. As confidence grew, ambition followed: “Women asked, ‘Why can’t we do a half marathon?’ So we added 21 km,” he added.

After the pandemic, that hunger deepened. “Women wanted to do more,” he says. This led to the ‘Spirit of Pinkathon’; a 150 km run across three days. Later, organisers felt ready for something even bigger. “We needed a motivation that allowed women to realise they have no limits,” Milind says, adding that Ankita Konwar, founder of Invincible Women, proposed the 100 km run.

Today, Pinkathon spans distances from 3 km to 100 km. “On February 15, we have the shorter runs. On February 14, at 5 am, we start the long-distance runs: 50 km, 75 km and 100 km. It’s a 24-hour event,” he shares. Those who complete the longest distances are invited on stage — not as champions, but as living possibilities.

The stories have become the soul of Pinkathon. “Last year, the oldest woman to complete 100 km was 67 years old. She started with 3 km. The oldest woman to complete 50 km was 74 years old — she also started with 3 km. When others saw them, belief shifted,” Milind shares with a bright smile and sense of accomplishment.

The stories have become the soul of Pinkathon. “Last year, the oldest woman to complete 100 km was 67 years old. She started with 3 km. The oldest woman to complete 50 km was 74 years old — she also started with 3 km. When others saw them, belief shifted,” Milind shares with a bright smile and sense of accomplishment.

As Pinkathon Hyderabad reaches its sixth edition, the most profound change Milind sees is confidence. “Women now feel they can do anything. Many arrive unsure, then see women with disabilities, visually impaired runners, older women, and mothers with babies. Pinkathon is even attempting a world record in Mumbai for participation by visually impaired women,” he shares.

What stands out is the absence of pressure. With longer lifespans, Milind believes fitness determines quality of life. “We may live up to 80 or 90 years, but how do you enjoy those years if you’re not fit?” he questions. He further cites his mother, 86 years old and still hiking, who began at 60. “That’s what longevity should look like,” he says.

They did — and more. “It showed how little we understand what women want,” he notes. Often called exceptional, he redirects attention: “Don’t look at me. Look at these women.” His role, he says, is simple: “Show the stories. That’s what creates change.”