'Babylon' movie review: Damien Chazelle celebrates and demystifies the allure of cinema

Anyone who has seen films made before the 60s knows Hollywood showed us a different, heavily sanitised version of the people who lived back then. Regardless of temperament, good or evil, what we saw in the movies were people who spoke clean, coherent English, wore classy costumes, and... remained clothed all the time. Of course, the Hays Code ensured that the films remained that way until the late 60s when the arrival of the ‘new wave’ of (liberated) filmmakers effectively ended that. In Babylon, Damien Chazelle paints a picture of Hollywood in the early 20s—the time of silent cinema through talkies—through the lens of a ‘liberated’ filmmaker. It’s as though he time-travelled to that time and showed us the ‘real’ picture. Or, let’s call it ‘alternate history’.

Chazelle goes so wild —in a way that Babylon could give Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street a run for its money. Like some of Scorsese’s most celebrated pictures, Babylon has characters spewing the choicest of expletives and indulging in some wince-inducing acts of depravity. A situation in the opening alone is essentially an analogy for the entire film. There is an attempt to transport an elephant on a vehicle meant to bear the weight of a horse. At one point, we get a quick close-up of the creature’s bottom while it defecates at us—well, the camera. That’s Babylon in a nutshell. Or, to be more specific, it’s representative of everything that happens to Manuel (Diego Calva), who, we later realise, is the film’s protagonist and, in effect, the moral compass.

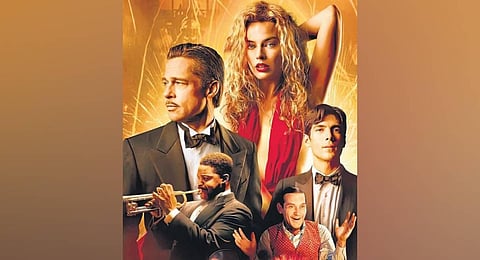

There is, of course, Brad Pitt and Margot Robbie as two actors—senior, junior— named Jack Conrad and Nellie LaRoy, respectively, who get equal prominence, but we see the entire story from Manuel’s point of view. I mentioned earlier the two different pictures of Hollywood presented by two different eras. But the ideas of Babylon are not just applicable to the American film industry alone; we can find messed up people in not just film industries all over the world but any industry that deals in fame and power.

For an outsider, a movie or a movie set may seem the most magical place on earth, but how does an insider, especially a seasoned one, feel about it? How fed up are they? Do they get burnt out to the extent that they lose their love for the movies? The outsider in Babylon is Manuel, who first encounters Jack Conrad and Nellie LaRoy at a Hollywood party that could be best described as the extreme version of that orgy in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut. If I were to apply the Hays Code to myself, I would describe it as a party featuring kinky behaviour involving certain bodily fluids and men gladly enjoying bottles getting shoved up their... you know where. And then there is, of course, the elephant whose services come in handy for an act of clever distraction.

In shooting this party, which takes up the first 30 mins before the film’s title shows up, Chazelle and cinematographer Linus Sandgren (La La Land, First Man) don’t hold back. The camera’s frenetic energy immediately evokes the films of Martin Scorsese, most notably Goodfellas and Casino. Babylon sees Chazelle accurately channeling the manic intensity of a Scorsese picture in multiple places. The last time someone did it so beautifully was Paul Thomas Anderson, in Boogie Nights. The orgy is shot in the same fashion as the Copacabana sequence in Goodfellas, the opening casino introduction in Casino, or the single-take nightclub coverage in Boogie Nights. A lot happens at this party, but it never loses focus on the principal characters and what they have to deal with. This sequence sets up the personalities of Jack and Nellie; it’s almost a microcosm of the worlds they would soon inhabit.

With a strong streak of self-destruction coursing through their DNA, Nellie and Jack both represent the allure and ugly side of the industry. While the former comes from an underprivileged background—the dilapidated home she shares with her father (Eric Roberts) suggests all kinds of morbid backstories—the latter enjoys a near-superstar status. Despite playing a character from the 1920s, Pitt occasionally mouths Italian words, as though he travelled forward in time, saw Fellini’s 8 1/2, and went back to do his best Guido impersonation. Perhaps Chazelle intended Jack as an amalgam of Guido and Inglourious Basterds’ Aldo Raine.

Interestingly, Babylon is set in the same period as another Scorsese picture, The Aviator, which also explored the transition from silent films to talkies. The only difference here is Howard Hughes was excited by the possibilities of dialogue-driven movies. Jack, on the other hand, finds himself slowly turning into a relic of a bygone era, kickstarting a downward spiral. The most painful moment from Babylon is an ironic one, which requires Pitt not to utter a single word: from a dark corner in a movie hall, Jack observes, with much sadness, audiences laughing at his dialogues from his maiden foray into talkies.

As for Margot Robbie, she has by now perfected the art of playing tormented characters. There is an incredibly brilliant stretch where Nellie has to prepare for a scene in her first talkie, and the anxiety experienced by her and all the characters in that situation is chillingly palpable. Just remembering only a few minutes from this segment gives me anxiety. I’m talking about an infinitely volatile situation where unforeseen events, played for laughs and otherwise, constantly play spoilsport, leading to multiple takes. If Hitchcock were alive today, he probably would’ve got a huge kick out of watching it, especially its darkly humorous culmination.

While on dark humour, we get another equally intense scenario where Manuel has to acquire a camera when one of them is destroyed on the set of an Austrian filmmaker shooting a medieval epic. (The real-life inspiration could be Fritz Lang shooting Die Nibelungen.) Chazelle shoots Manuel’s dilemma like an action movie, with the expert hands of cinematographer Linus Sandgren and editor Tom Cross rising to the challenge of getting the rhythm and mood right. The team also throw in a simultaneous situation where Nellie is shooting her debut scene, where she demonstrates an astonishing ability for naturally-induced tears, sometimes even bringing them down to one or two drops.

Babylon also explores the crisis of an African-American jazz trumpet player Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo), who has to deal with issues of identity and colour while shooting for a new movie. Palmer is just one of the characters in Babylon who find their true selves diluted after getting into the movie business. This struggle to stay real affects Nellie the most; she makes an outrageous display of her displeasure at a party populated by ‘intellectuals’. And I won’t even get into another terrifying situation involving Manuel, where the hellish atmosphere recalls some Gaspar Noe films.

With all these extremely trying circumstances, how do you keep your love for cinema alive then? This query must’ve been on Chazelle’s mind when he envisioned a climactic montage scene, which, again, takes us on a ‘time trip’. I mentioned earlier that the film occasionally has the quality of a time-travel story, and this brilliantly edited sequence, in particular, makes that element feel more pronounced.

Film: Babylon

Director: Damien Chazelle

Cast: Diego Calva, Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie

Streamer: Amazon Prime Video

Rating: 4/5