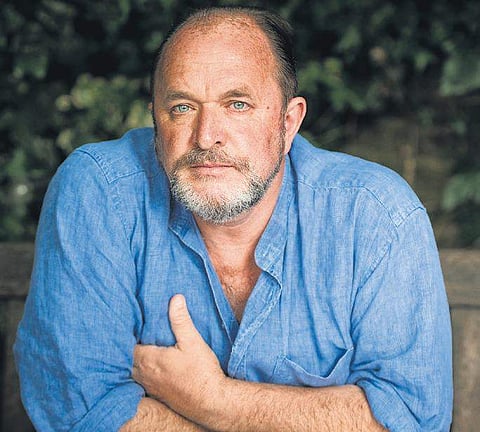

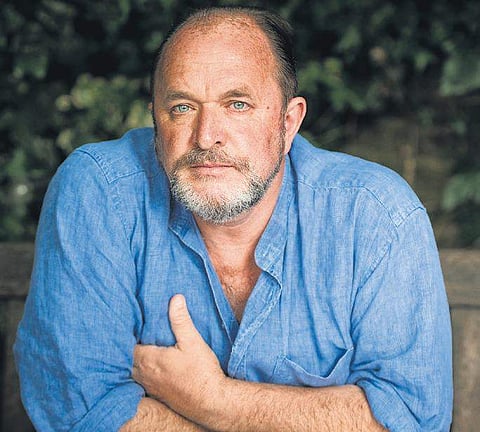

William Dalrymple's The Anarchy is his fourth book, based on a historical period that he says has always attracted him and yet, according to him, has remained a very under-studied period. “I think people who haven’t read my books often assume that I have been writing about the Mughals non-stop for thirty years, but actually it’s this transitional period, sometimes called the Twilight, which I call The Anarchy, which is just fascinating, very under-studied and full of colour and interest and surprise,” he tells us, as he begins his book tour in India.

What makes this historical account all the more relevant to our times?

What this book fixes on is the fact that India was actually conquered not by a nation state, but far more sinisterly, by a corporation. And, the East India Company was not the British Government. Over the course of the 18th century, it became more closely aligned with the British Government, so that by the early 19th century, it had become a sort of public-private partnership.

ALSO READ | Author William Dalrymple's latest photo exhibition is worth a thousand words

But for the first 200 years, it was very much a libertarian dream of this unregulated capitalist monster, which is doing its own thing, and often training its guns on the British state in the sense of bribing MPs and lobbying the parliament to forward its own interests over the state, and this was well known in the 18th century.

If you read critique in the British newspapers of the 18th century, everyone was appalled that a corporation run by a body of merchants out of a boardroom in the city of London was running, what was – after the Fall of America or the Independence of America – nominally, the most important British colony. When I have been touring this book around Britain, I have been emphasising the loot and plunder that the British don’t know.

The British always long to see the redeeming side of their empire, wanting, of course, to believe the best of their ancestors and so, I think it is very important to give it straight that this was about looting and not about building railways or any of the rest of it. One of the things I’m emphasising on in India, is the degree to which it was done, through the collaborations.

So, did you intend this to be a cautionary tale?

Yes. There are two stories really in this book. One is the story that I have just described, of how a company conquered India. But, it’s also a more general story about the power of the corporation versus the power of the State. I had no idea when I began this book six years ago in 2013, that (American politician, former academic) Elizabeth Warren will be going around on her campaign trail lecturing on this every time, about the power of the corporations. I mean, I very much plough my own furrow and don’t particularly choose which book to write on the basis of current trends, and as these books take at least three years, or sometimes six, it would be foolish if I did. But it has been incredibly good timing, as far as I’m concerned.

What historical sources did you draw upon while sketching out characters like Shah Alam, Ghulam Qadir and Mahadaji Scindia?

The sources for the company are obvious. They are the ones in the British Library,

and the National Archives, which are the papers from Fort Williams, which was the Company Headquarters in India. But to write about Shah Alam, Ghulam Qadir and so on, you have to go to Mughal sources. Particularly useful was this new Shah Alam Nama (by Munshi Munna Lal) that we found in the Research Institute in Tonk in Rajasthan, which is an incredibly important and previously unused source. There is a wonderful Ibrat Nama by Fakir Khair ud-Din Illahabadi.

Ibrat Namas are like cautionary tales, books of admonition, and we found this particular one in the British Library. There is also a Tarikh-i Muzaffari by Mohammad Ali Khan Ansari of Panipat. He writes particularly on what’s going on in Bihar and Bengal. So, it’s a very well-covered period. The most revealing sources have been in English for a long time like Ghulam Hussain Khan’s Seir Mutaqherin, or Review of Modern Times that was available in English, but not often used, as it’s quite dense. It’s four volumes long and written in 18th century English, and so people have not realised the gems it contains. It contains very detailed first-hand portraits of a lot of the major characters, including Shah Alam.

What are you working on next?

I want to do some sort of a big art history or cultural history project. And the current form I think it is in, would be something like a history of the Indian Civilisation in 21 cities. It’s a big project. I’m now in my mid-50s. If I don’t take on the big projects now, then when? It’s sort of Mohenjodaro, Taksila, Kanchipuram, Mahabalipuram, Tanjore, Vijaynagar, Bijapur, Fatehpur Sikri, Kishangarh, New Delhi... something like that. I want to write more about art and culture and less about politics next.

Through The Anarchy, one can gauge how Dalrymple doesn’t like the British, but he has to admire their ruthlessness.