It is a dubious reviewer claim that a book needs to be read by all. That said, Crimson Spring by Navtej Sarna is essential reading for all Indians. This ought to be mandatory reading in high schools and colleges; furthermore, every reader ideally should distribute five copies among those who

lack access.

A book such as this comes into the public domain maybe once in a lifetime, combining flawless writing and acute research around a historical event so momentous it may never be forgotten. Not only is the book

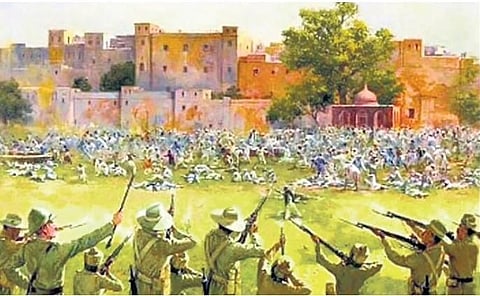

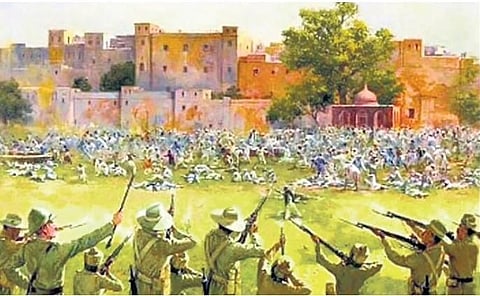

a masterclass in how historical fiction ought to be, the subject matter of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre comes alive in this retelling, touching a submerged chord that makes each of us who we are today.

Historical fiction is a tricky tightrope and far too few authors do justice to this genre. All too often, the history is inaccurate or anachronistic, and the fiction, almost unreadable. This book is primarily literary fiction of quality earthed through refined research by a master who treats his fictional protagonists with skill and sensitivity while ensuring the horror of the tragedy and its aftermath hover between the lines.

As homage to those martyred in that gory run-up to Independence for India, this has been written with the lyricism, precision and passion of prayer. Nine lives have been carefully selected, defined and made familiar in their human frailties and aspirations before being sent towards their predetermined fate at Jallianwala Bagh.

Enmeshed, these lives underline the scale of the tragedy and fill the reader with a sense of grief and blinding loss. These are people like us–– trying to do their best during the worst of times––and only by being in the right place at the wrong time meet with their gory destinies. Among them, Lance Naik Kirpal Singh visits Amritsar after the Great War in far colder lands.

Using Indian soldiers for their overseas wars did not make the British kinder to those who fought shoulder to shoulder with them in freezing trenches. The unrest at Amritsar has halted train service, forcing Kirpal Singh to make the last leg of his journey perched on a farmer’s bullock cart. He looks forward to meeting his father and maternal uncle at Jallianwala Bagh on Baisakhi.

Through the eyes of the young vakil, Gurnam Singh Gambhir, we watch the unrest as the hapless populace’s resistance is quelled by increasing cycles of violence. In essence, this is a polyptych depicting Punjab in all its glory and minutiae. Oftentimes the past, present and future of people may be defined by a brief epoch, and Amritsar, in the year 1919, delineated here in miniaturist detail, permits an instant understanding of an entire culture and its populace, whether Sikh, Muslim or Hindu.

Deft touches to reconstruct history, even as we marvel at how much like us their lives were. The wrenching imagery and finesse are reserved for the actual carnage as survivors and family members walk among the dying and the dead to claim their own, numb in the immensity of what they witness. There is a term for it in Punjabi, ghallughara or holocaust that a benumbed Bhagwan Singh can barely enunciate even as he relates to Gurnam Singh the unspeakable.

The throbbing pulse of Punjab could only have been so intimately portrayed by someone from within, at ease with the lifestyle and familiar with intrinsic physical details such as the far-flung tiny villages of Tibba, Dharamsinghwala or Jutogh. It is to the author’s credit that the larger national narrative

has not been bypassed, including the words and deeds of Mahatma Gandhi, Subhash Chandra Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, and the Ghadar Movement, as well as Porter, Lloyd, the Rowlatt Act, O’Dwyer, and Dyer, the butcher himself. They take up less space in the narrative though: the lives of the British, the bloodthirst of the Raj and some of its officers, and their human experiences including the stillbirth of a girl child to Chief Secretary Hugh Porter’s wife Milly, are sharply etched too.

Moving, powerful and written almost as a service to the nation, this book revives, as few books do, the recesses of collective memories. And Aleph Book Company still remains uncompromising in the production of superlative literature as this book testifies.