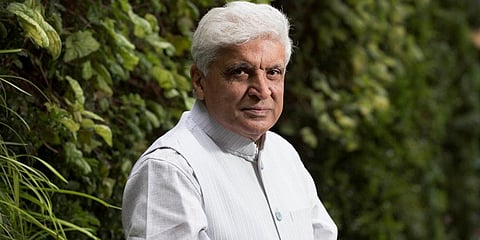

If one were to list the most popular present-day Hindi film personalities who aren’t actors, Javed Akhtar’s name would probably come pretty much near the top. Much- acclaimed, frequently awarded, he wears many hats. Lyricist par excellence. Writer—of both script and dialogue—for some

of Hindi cinema’s most iconic hits such as Sholay, Zanjeer, Deewaar and Seeta aur Geeta. Urdu poet. Social activist.

But who, really, is Javed Akhtar? Who is the man behind the immensely successful professional? What are his antecedents, of course, but more importantly, what sort of person is he? Nasreen Munni Kabir, long associated with the luminaries of the Hindi film industry and with many similar ‘conversational memoirs’ and biographies to her credit (Gulzar, Waheeda Rehman, AR Rahman and Lata Mangeshkar among them), interviews Akhtar in Talking Life, the third in a series of conversations with the writer-poet. In the earlier books, Talking Films and Talking Songs, the focus has been on two of the main areas of his professional excellence. Here, while some of that does come through (obviously, given that Akhtar has been writing for cinema in different roles since the 1960s), the emphasis is more on his personal life.

Talking Life is a chapterless book; Kabir’s questions are followed by Akhtar’s answers, followed by more questions, in a free-flowing, realistic chat that often reveals the comfort level between the interviewer and interviewee. They begin with him talking at length about his family, starting with his paternal great-great-grandfather, Fazl-e-Imam, who was the Sadr-us-Sudur or Chief Justice of the Mughal court. From here, the writer moves forward immediately to Fazl-e-Imam’s son, the illustrious poet and philosopher Allama Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi, who edited Mirza Ghalib’s Dewan, served as Chief Justice for the state of Awadh, and was sent to the Andamans’ notorious Kaala Paani, the Cellular Jail, for the active role he played in the uprising of 1857.

As Akhtar talks of his forebears, it’s interesting to see these two major threads—of poetry on the one hand, political activism on the other—play out again and again, one generation after the other. From Akhtar’s paternal grandfather, the poet Muztar Khairabadi to his much-respected, famous father, the poet and lyricist Jan Nisar Akhtar; from his maternal uncle, the renowned poet Majaz Lakhnawi to his younger brother, Ansar Harwani, a freedom fighter, who was jailed frequently for his anti-British activities: this has been a family both of letters and rebellion.

Akhtar’s mother, Safia, who passed away when he was just eight years old, is one of the most poignant figures in the book, remembered with emotion. So, too, are other relatives, both past and present, including his aunt and uncle (who looked after him for several years after Safia’s death), and his maternal grandparents. When he was not quite 20 years old, he came away to Bombay, and from hereon, the people whom he mostly discusses are those whom he got to know through work or in ways related to it. Contrary to what one may expect, not all of them are celebrities. Akhtar looks back with affection and obvious respect at a diverse group of people. The many people who allowed him room to live and sleep for free when he had no place to call home––the chatty owner of a ‘speakeasy’; a ticket checker of the Bombay local; the staff members who have been part of his household for many years.

Although it’s arranged in a roughly chronological order, Talking Life doesn’t always go the way one expects it to. There are digressions: now and then, the topic drifts away into other, related, realms. Akhtar explains the basics of Urdu poetry. He talks of his philosophy of life. He and Kabir discuss everything from his favourite actors to his working partnership with Salim Khan, from his campaign to have the Copyright Act amended to his relationship with his father. One gets the impression of an informal, organic conversation rather than a staged interview.

What adds to the readability of this book is the honesty and frankness that Akhtar brings to it: he is candid about his own faults and flaws, even regretful. There is a certain humbleness here, a willingness to admit to wrong decisions and weaknesses. No salacious gossip, however, is part of this frankness; there’s dignity here, and a good sense of what is for public consumption and what is not. The forthrightness, the delightful sense of humour, and the easy way in which Akhtar manages to inform and educate (on cinema, poetry, copyright laws, and more), all of these help make Talking Life a readable, interesting memoir.