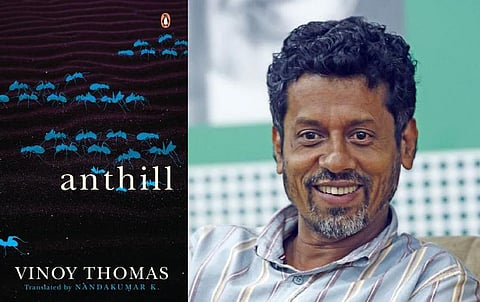

It is inevitable that a tale with more than 200 characters, each with an intriguing backstory, wrapped in a complex yet compelling narrative with well-timed humour, will be both tough and enjoyable. Vinoy Thomas’s Anthill (originally written in Malayalam as Puttu), being a perfect blend of all of the above, certainly leaves a mark.

It is the story of Perumpadians, residents of Perumpadi. In this remote village located on the border between the states of Kerala and Karnataka, nobody pries on anyone’s past, because everyone has something to hide—someone has impregnated his own daughter, a woman had an illicit relationship with her brother-in-law, or a man has eloped leaving behind his wife and children. But all of that is irrelevant for the residents, for Perumpadi is a refuge for ‘sinners’ looking for a fresh start.

At the centre of the novel is an institution called the ‘reformation house’, although no sign board is there to notify that. It is at this place where the scandalous tales in the lives of the villagers play out. In this developing community, there is no panchayat to decide on day-to-day issues. Paul Sir is introduced as the adjudicator. Once he passes away, his son Jeramias assumes the responsibility to become the president of the village. His is the final word, one that is unequivocally accepted by everyone. Jeramias preoccupation with his work, however, soon becomes his undoing, once he begins neglecting his own family––a unit that, especially in Indian society, plays an important role in defining moral codes. So much so that any deviation can often result in social boycott.

Thomas, however, creates a world without judgement. With characters such as Bhavani Daivam, Neerkuzhi Achan, Kocha Raghavan, Neeru Joseph, Bunny Sunny and Rairu Nair, he puts the spotlight on the complexity of human existence. He writes about conflicts, questions of morality, gender, sex and identity in a way that upholds the value of second chances, as is made evident through the stories of many of the Perumpadians who, over a period of time, start showing signs of “reform”.

While reading Anthill, one can’t help but be reminded about the world that Gabriel García Márquez had imagined in his stories. Though the novel does not carry any obvious resemblance to a particular work by the Colombian writer, the evocative style of writing seems inspired. For instance, the family of Paul

Sir and his reformation house appears to draw heavily from the multi-generational story of the Buendia family in Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude.

What is most commendable about this book though is that the translator, Nandakumar K, decided to retain the local references from the original––and there are far too many––at the risk of getting low readership. But the book manages to make up for it with the effortlessly knit stand-alone stories of hundreds of characters in a way that nothing seems to have been lost in translation.

The non-linear narrative moves slowly and in an episodic manner. The challenge is to familiarise with the details thrown the reader’s way at the beginning of each chapter, but the simple character sketches help join the dots, making the novel a smooth read, one that makes for a worthy incorporation to one’s book collections. It is a story that can and must be revisited.