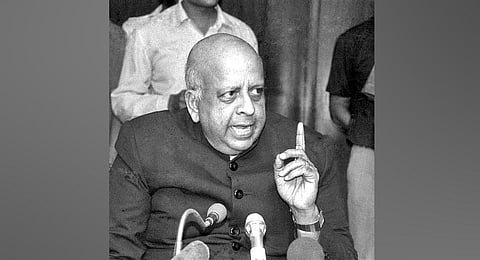

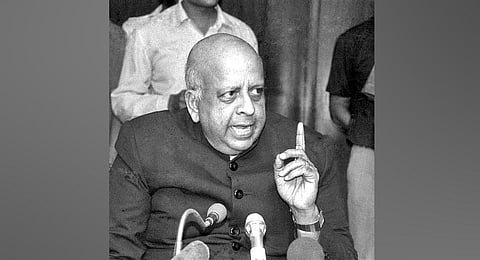

Tirunellai Narayana Iyer Seshan was a household name, and probably still is. He was the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) from December 1990 to December 1996. Electoral reforms cover a vast area, and are an ongoing process, but several bits we take for granted—model code of conduct, voter IDs, curbs on electoral malpractices and limits on expenditure. All of these owe their existence to Seshan’s stint as CEC. The Seshan imprint on electoral reform, therefore, is considerable and undeniable. His career can be divided into two parts: there was a period before becoming CEC—joining IAS, working in Madras (Tamil Nadu), Atomic Energy Commission, Department of Space, Cabinet Secretary and Planning Commission (Member); and, there was a period after CEC—contesting the 1997 Presidential elections, fighting against L K Advani on a Congress ticket in 1999, and receiving the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1996 for government service.

A stellar career in the bureaucracy, and thereafter, though, does not make for a stellar author. This is not the first book that Seshan has written. There were two earlier ones in 1995—one a collection of his speeches, and the second co-authored with journalist Sanjoy Hazarika. Since Seshan died in 2019, the autobiography has been published posthumously. Of the 23 chapters, six are devoted to the pre-CEC period. In other words, Seshan himself believed CEC was the pinnacle of his career, as it probably was.

As one ages, one mellows. As one ages, one becomes kinder and less bitter. As one ages, one finds internal peace and is less harsh on people. As one ages, one becomes wise. But those principles are for ordinary mortals, and Seshan didn’t regard himself as one.

An autobiography can be engagingly written and can be a good read. This one is neither and is of value only because it documents the process of electoral reforms at the time. Despite having two books to his credit, the memoir appears to have been written by a bureaucrat, not an author. That too, one who is self-opinionated and self-pompous. These words sound harsh, especially if the author is now deceased. Hence, some examples.

“In the Indian government, there are many useless institutions, and the highest of them was the Planning Commission.

I worked for nearly a year as a member of the Planning Commission, and what I did there is not worth talking about. The pace of work in Yojana Bhawan was also hopelessly slow.” All that might be true, and the Planning Commission has now yielded to Niti Aayog. But, there are people who would have hesitated to write this about an organisation they worked in. “It was Swamy’s (Subramanian) responsibility to find a CEC. But Swamy had later said that I had begged him to get this job. What led him to say that is not clear to me even today. Was it because Swamy and I were no longer on friendly terms or was there some other reason.”

There is too long a description of what transpired when MS Gill and TS Krishnamurty joined as commissioners to quote, but here is one bit. “Then, Krishnamurty pulled up his left leg and put his booted foot on top of an office table. He lifted his trousers and said, ‘This is where my vein was cut in order to do bypass surgery.’ He then walked up to my table: ‘Are you willing to shake hands?’ Then he came around the table and said, ‘Are you willing to embrace me?’” The incident may have happened, but does one write about it? “(Vir) Sanghvi then suggested about the president or PM’s posts.

I said I would accept no less, not even the home minister’s post. To him, that sounded arrogant. I replied that I had not applied for either yet, and added that if the public of the country would chase me, then I would run for office”. This should reek of arrogance not just to Sanghvi, but to everyone.

As one reads the autobiography, Seshan doesn’t come across as an endearing person, nor does he come across as someone to whom humility comes naturally. There have been others, in higher positions, who have written autobiographies without sounding so arrogant. The incidents in the book document how he managed to work the system and use his contacts to rise up the greasy pole. A case in point is how he prevailed upon the then PM (Indira Gandhi) to expunge an adverse CR (confidential report) remark written by Homi Sethna, when Seshan was at the Atomic Energy Commission. The expunged remarks were, “He is aggressive, abrasive and is a bully to those under him.” The comments are vindicated by the memoir.

Towards the end, Seshan writes, “I could go out in peace, happy that I had done my job.” In that case, one doesn’t need to justify anything to the rest of the world. The book, however, is steeped in self-justification.