The average Indian probably encounters, in an indirect way, one of ancient India’s greatest rulers several times a day in the chakra that adorns the Tricolour as well as the four-lion National Emblem that appears on government documents, government buildings and currency notes.

But how many of us really know much about the famous king, Ashoka? A few, with a bent towards history, may know of his infamous Kalinga campaign, and how, in the wake of the bloody war and the thousands of dead it left behind, he repented and turned to religion. Some may also know something of how he sent Buddhist missions to other countries such as Sri Lanka. Others may have heard of dhamma. But, largely, the majority only thinks of Ashoka as ‘great’, with little idea of what the greatness entailed.

There is, however, much more to the ruler, as Indologist Patrick Olivelle sets out to explain in Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King, the inaugural title in a series (edited by Ramachandra Guha) called ‘Indian Lives’.

The author begins the book with a prologue that shows how important the man once was—emperor of a subcontinental empire that was surpassed only by that of the British, almost 2,000 years later. Yet, a ruler of whom what is commonly known is relatively little because there is a ‘legendary’ Ashoka—the man written about in Buddhist hagiographies and other texts that don’t have much to do with fact; and a ‘historical’ Ashoka—glimpsed through the many inscriptions he left scattered about his territories.

Olivelle goes on to describe how the British scholar and antiquarian, James Prinsep, in 1837, succeeded in deciphering the Brahmi script, finally allowing the king’s many inscriptions to be read. It is largely based on these writings—totalling a little over 4,000 words—that Olivelle describes Ashoka in his book.

He divides it into four parts and devotes each to understanding the different aspects of the great personality.

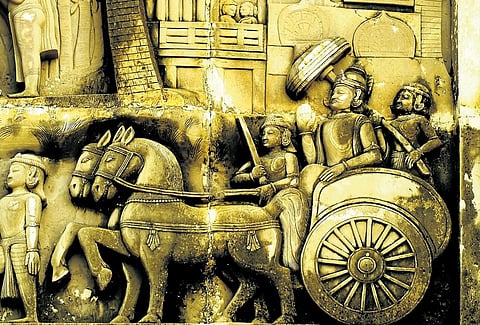

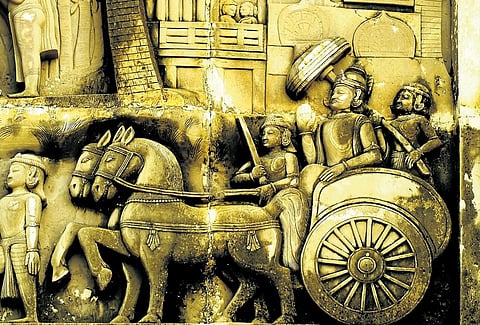

Part 1, ‘Raja: Ashoka the King’, begins with a brief introduction to the Mauryans before going on to examine his role as a king: his attitudes (so very different from other rulers, across time and space), his contribution as a builder, writer, diplomat and father-figure to his people among others.

In the following part, ‘Upasaka: Ashoka the Buddhist’, Olivelle emphasises the early edicts of Ashoka, which show his initial years as a devotee, his ‘striving’, involvement with the sangha and attempts at evangelisation.

After his early fervour as a Buddhist, Ashoka turned (or so his inscriptions reveal), in later years, to a more non-denominational, non-specific dhamma (the Prakrit equivalent of the Sanskrit ‘dharma’), a philosophy that sought, like that of Akbar’s Din-e-Ilahi, to promote syncretism. This forms the subject of Part 3, ‘Dharma: Ashoka the Moral Philosopher’.

The last section of the book, ‘Pasanda: Ashoka the Ecumenist’, delves deeper to explore connected concepts such as the existence of pasandas or organised religious groups, and how Ashoka related to them. A glossary and an appendix—the latter containing an English translation of, and some basic notes about, each of Ashoka’s inscriptions—round off the book.

Ashoka is well written, and the author, keeping in mind a readership not necessarily restricted to academia, takes care to steer clear of jargon. He goes deep into detail, analysing each of Ashoka’s inscriptions to see how it offers insights into not just the emperor’s psyche, but also into the times he lived in—how people felt about religion, what rituals and practices might have been prevalent, how societies and rulers behaved.

He uses other sources, from Brahmanical texts to the accounts of the Greek diplomat Megasthenes, from Patanjali’s grammar to Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Apastamba’s Dharmasutra, besides many modern scholars, to shed light on Ashoka, his possible motivations and more.

He minutely examines each of the inscriptions to show how it may reflect different aspects of the figure’s life and thoughts.

This means that Olivelle returns again and again to an inscription, and (given that several of these are fairly similar in tone), it can come across as somewhat repetitive.

Despite that, however, this remains an informative work of literature, not the usual, often-dry litany of battles and campaigns and administrative reforms most lives of ancient rulers are relegated to in modern-day accounts. Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King, instead, is a thought-provoking, enlightening book.