The history of Hindi cinema has some very distinctive elements for pretty much every decade

of its existence, especially after the coming of sound. The 40s were for socials and mythologicals; the 50s too, but with the added charm of great music. The 60s were all-colour, singing-dancing in foreign locales, glitzy and glamorous.

The 70s was the time of rather more diverse elements. On one end was the Big B’s ‘angry young man’, the boyish energy of Rishi Kapoor, and the multi-starrers that amped up the idea of the ‘masala film’ to the max. On the other end of the spectrum was the gritty and realistic parallel cinema of filmmakers such as Mani Kaul and Shyam Benegal. Between the two opposite poles was ‘middle’ cinema––pioneered most prominently by Hrishikesh Mukherjee in the 50s and 60s, but ruled by Basu Chatterji in the 70s.

With productions such as Khatta Meetha, Rajnigandha, Piya ka Ghar, Chhoti si Baat and Baton Baton Mein among many others, Chatterji made films about the common man––everyday, regular people whom his audiences could identify with. People with lives like ours––who looked like us, and had worries and challenges like us too. People who (to paraphrase a very popular song from Khatta Meetha, ‘Thoda hai, thode ki zarurat hai’) had little, but could be happy in that, because they needed little.

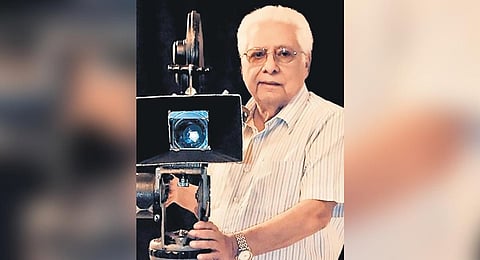

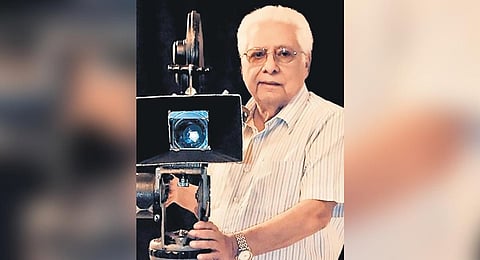

How the filmmaker became the master of middle cinema is what Anirudha Bhattacharjee sets out to explore in Basu Chatterji and Middle-of-the-Road Cinema. While the author does begin the book with a brief account of Basu-da’s (as he was known) early life, this is by no means a biography. It is, instead, a journey into his cinema, along with his forays into related fields such as television series and telefilms.

Bhattacharjee divides the book into three parts. The first one traces Basu-da’s career up to the release of his first film, Sara Aakash in 1969. Part 2 focuses on the bulk of his filmmaking career, from the big hits that marked the mid-70s to the also-rans–– the films that either never quite made a mark or those (Hamari Bahu Alka, Pasand Apni Apni) that are perhaps more loved today than they were at the time of their release. The final section is about the director’s work in television, including series such as Rajani and Byomkesh Bakshi, as well as his migration into Bengali cinema.

Bhattacharjee’s research is extensive, quoting from interviews with Basu-da himself, with dozens of other cast and crew members of his films, family members, friends, associates and others, who provide valuable insights into his work. There are also excerpts from articles and books, as well as a small but interesting selection of photographs.

All of these come together to form an interesting account of Chatterji’s filmography––how they came to be, what elements (a director cameo, rain, a female character named Prabha, references to popular cinema and its music) became almost standard in a Basu Chatterji-film, how his cinema defined the director, and more. What comes through forcefully is the way Basu-da’s personality seems to be reflected in his cinema. For instance, one cast member after another talks fondly in interviews of how unassuming he was, and how he managed to make the atmosphere on a set seem like being part of a family. One gets the impression of a Khatta Meetha or a Baton Baton Mein being replicated offscreen too.

While there are insights into Chatterji’s relationships with the actors (especially those who owed their first big break to him, including Amol Palekar, Zarina Wahab, Vidya Sinha and Bindiya Goswami), the book also sheds light on how he interacted with members of his technical crew. Most importantly, one gets a feeling of how Basu-da, often referred to as the ‘producer’s director’, interacted with those who bankrolled his films. His close watch on funds and his refusal to waste time, money or other resources, are a reflection on his sense of ethics, of course, but they contributed, too, as Bhattacharjee shows, to the eventual decline of his cinema. The author’s willingness to touch on Chatterji’s shortcomings helps make this book a convincing and balanced read. Bhattacharjee, in fact, goes on to point out all the goofs in the director’s films––a lack of logic, gaps in continuity, and so on. The outcome is a portrait of

a filmmaker, who was also very human––talented and vastly accomplished, yes, but also a genius with feet of clay. He was real, down to earth, just like the films he made.

Basu Chatterji and Middle-of-the-Road Cinema

By: Anirudha Bhattacharjee

Publisher: Penguin

Pages: 306

Price: Rs 699