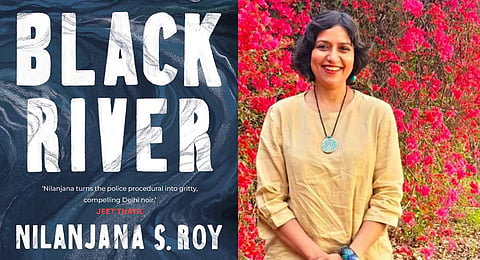

A police procedural. Classic noir fiction. A reflective look at the elliptical loops around a crime. Nilanjana Roy’s Black River is all that and more. With this work, Roy brings to her crime fiction debut the skill she employed in her delightful cat books The Wildings and The Hundred Names of Darkness. It’s the account of a solved murder mystery that keeps to a structured format, but also seamlessly combines the elements of a thriller with socio-political commentary. Rather like Sonia Faleiro in her book The Good Girls or the cult film Chinatown, here too the investigation of the crime reveals the deep rot that lurks just beneath. In the process, the story is not just about a crime committed, but a compassionate look at what ails the larger society.

A perceptive reader will quickly find a connecting link between the cats of Roy’s earlier books, the villagers of Teetarpur, and those who live in makeshift huts along the Yamuna in this one––all of them, mostly outsiders, and this is their tale. The black river of the title is the beleaguered Yamuna, and the story tells of what takes place near it and at some distance from it, too.

A little girl has been murdered in a village, which is a two-hour drive from the capital, and while the tale proceeds in pretty much the manner you want crime thrillers to move forward, it is Roy’s evocative sketches of the characters, including the red herrings, that really tugs at the reader’s heart. While policemen Ombir Singh and Bhim Sain attend to the case with the occasional pang because they knew the victim Munia as well as her father Chand, they are your archetypal cops who want to dispose of the case as quickly and conveniently as possible.

A mentally challenged man was seen at the site of the crime and given that he is Muslim, the village’s sectarian emotions are immediately set on the boil.

Chand won’t be fobbed off easily and wants justice for the loss of his beloved daughter. Ombir might be a hardened policeman, one who doesn’t necessarily believe in the concept of justice, but loose ends that poke him in the eye trouble him, and he wants to investigate further.

Roy first sets the crispest mise-en-scene, then using the Muslim angle to widen the loop of her story, she gives us Chand’s backstory, as well as that of his closest friends Badshah Miyan and Rabia. After that, she takes us to a locality in the capital city, and shows us how people there, slowly but firmly, are turning against the Muslims and harassing them to no end, despite the latter community ‘making themselves smaller and smaller’. As Rabia muses, to not look obviously Muslim is a convenience, sometimes even a necessity, but that often feels like a betrayal. There is a passage detailing what Muslim women in the locality have to go through while walking to their homes, fact dovetailed into fiction, upon reading which the reader’s heart hammers.

This is more than just a murder mystery, because the reader quickly arrives at the killer’s identity. The book goes beyond the whodunit to give a look into the hearts and minds of people who live lavishly and well, people who eke out a hard living, people who kill without a second thought and people who are killed. People who spread evil like mould wherever they land. It is also a look at how the impoverished live day-to-day in temporary dwellings that can be and often are razed to the ground on demolition and beautification drives. It is a look at the hopes and tentative dreams of those who live on the fringe.

It is the continuing story of land grabbing––forest land in this case. It also is a look at just what we have done to the Yamuna: ‘For the most part, Delhi turns its back on her, staining her swollen body with its ashes and garbage and sewage, choking her with the city’s waste, its discards, its corpses and diseases.’

The author has stated that this book has no heroes; that is as may be, but the reader’s sympathy for the gruff Chand who so loved his little girl, unwittingly or otherwise, makes a hero of him. Roy also makes the reader a sympathetic party to the means by which Chand attempts to achieve closure of sorts on his terrible loss.