'Travellers in the Golden Realm' book review: Dispelling the colonial hangover

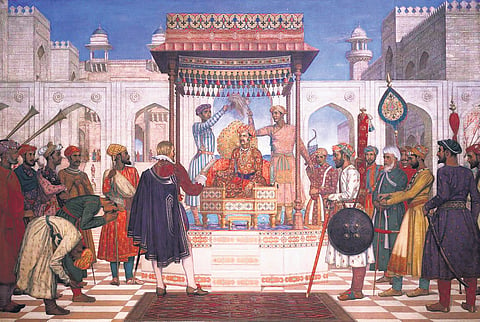

In her book, Travellers in the Golden Realm, Lubaaba Al-Azami mentions a mural in St Stephen’s Hall at London’s Palace of Westminster. The painting imagines the embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the court of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1615. Painted by William Rothenstein in 1927, the mural shows Roe holding a scroll while standing in front of Jahangir, who is seated on a throne amid courtiers, soldiers and attendants. Though Roe stands while Jahangir sits, the implication is clear: they are on an equal footing. It shows, in Roe’s stance and, in the fact that the only two servitors bowing deeply are behind Roe, not in front of Jahangir.

Compare this to a contemporary Mughal painting depicting Roe at Jahangir’s court: Jahangir investing a courtier with a robe of honour, watched by Roe, shows the English ambassador tucked away among the rank and file of the court. He is not the centre of attention; he is not the star of the show. The difference between the two depictions is stark.

In Travellers in the Golden Realm, Al-Azami shows how skewed is the common perception—created by centuries of erasure of the truth—that the English and India were on a level footing. This, as Al-Azami traces the evolution of English travellers to India, is shown to be far from the truth. Even the East India Company (EIC), of which this book almost comprises a history, ended up in India accidentally. Their primary target were the spice islands of the Far East; but since thick English broadcloth—about the only thing they could offer in exchange—had no market there, the EIC turned its gaze India-wards, from where it could source Indian calicos, much prized, to be sold in the Far East for the nutmeg, mace and cinnamon the English needed.

And yet, as Al-Azami shows, long before the EIC’s arrival in India, there had been other travellers too, making the long, arduous journey from England to India: Thomas Stephens, for instance, who arrived as part of a Jesuit mission during the reign of Akbar, and spent the rest of his life in India; or Ralph Fitch, the first Englishman to spend a considerable time travelling across India. There are well-known names here, such as Captain William Hawkins, and ‘the world’s first backpacker’ (as travel writer Ed Peters dubs him), Thomas Coryate. There are also lesser-known but equally interesting characters: John Mildenhall, for one, who called himself Elizabeth I’s ambassador without being anything of the sort; or the arrogant and peacocky William Norris, who wrecked an already doomed embassy to the court of Aurangzeb.

While the stories of these varied men who journeyed to Mughal India are fascinating, equally fascinating is the story of how England’s fortunes were changing through this period. How politics across Europe, and as far away as the Ottoman Empire and Persia, were shaping England’s motivations, and how that translated into England’s dealings with India—both through the EIC, and outside of it.

Woven into the story of England and the EIC are other histories: of the Mughals, their empire so wealthy that England was of no account to them; of conflicts between the English, the Portuguese and the Dutch over (and in) India; of women who stood out in a world dominated by men—powerful Mughal women like Noorjehan and Jahanara, of course, but also less famous women like Maryam Khan, an Armenian Christian of the Mughal court; and the Circassian-born Persian, Lady Teresa Sampsonia Sherley, both of whom accompanied their English husbands to England.

And there is the way ‘Mughal India connected England to the World’, the subtitle of this book. Through her exposition of the EIC’s evolution and growth, Al-Azami shows the even darker underbelly of the trade. On the one hand, the EIC’s need for Indian goods compelled them to transport silver from the Americas and Japan to India; on the other, the Indian demand for ivory made them turn to West Africa, from where they soon launched into an extremely lucrative, and reprehensible, slave trade.

The subtitle of this book is perhaps a little inaccurate. While the book does describe how England’s greed for India’s wealth pushed it to forge links with lands around the globe, that comes across more as a secondary element of the book. What dominates is the story of English travellers to India, the EIC, and their interactions with India during the reigns of the first five Mughal emperors.

A meticulously researched, well-written book, Travellers in the Golden Realm is both immensely informative as well as entertaining: a must-read for anybody interested in India’s colonial history.